In 1897, a few months from death, Johannes Brahms could be found in front of his stove surrounded by pages of personal correspondence and sheet music. With no wife or children to protect his legacy, the revered Herr Doktor Brahms would do the necessary editing himself: up to the mark or in the fire.

On the hundredth anniversary of Brahms’ death, Jan Swafford’s masterful study of the composer simply entitled, “Johannes Brahms: A Biography,” was published. One of the most infuriating aspects of Swafford’s research must have been Brahms’ ruthless purging of his personal documents. In the end, however, what Brahms allowed to remain and what he saw fit to destroy assist Swafford in finding the essence of his character: “Pieces of the sort Beethoven and Mozart put out as minor but workable, Brahms put in the stove. As far as he could assess what he had written, he wanted to issue nothing but masterpieces.”

Often decried as tactless, Brahms simply did not relax for others the exacting standards he held for himself. Celebrated piano virtuoso Clara Schumann admitted she feared to play around him. “His criticisms are too sharp,” she told a friend, “And unfortunately he’s always right.” In part, this perfectionism may be ascribed to his own disciplined training as a virtuoso from a young age but the broader circumstances of Brahms’ childhood suggest deeper roots.

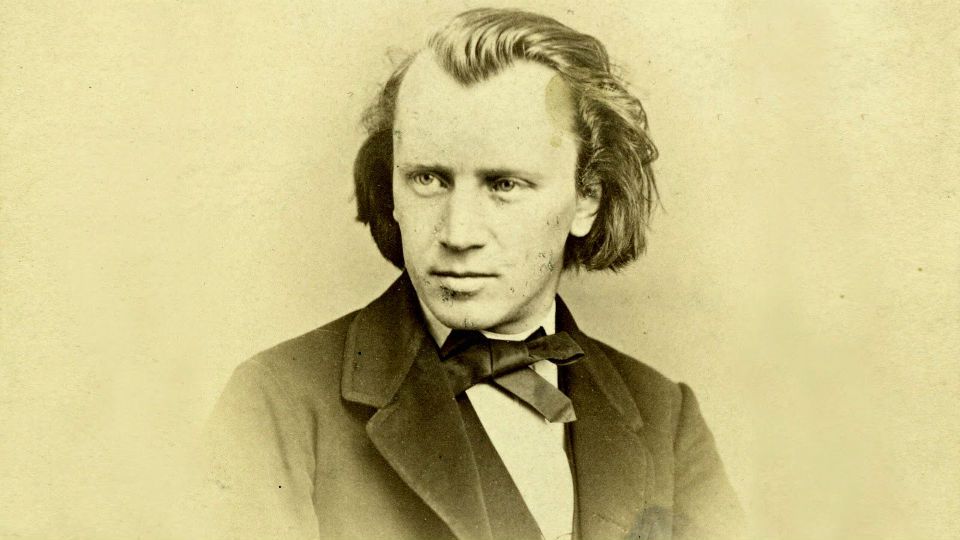

On May 7, 1833, Johannes was born to Christiane and Johann Jakob Brahms in the Gängeviertel area of Hamburg. Christiane was an accomplished seamstress and seventeen years older than her husband. Johann Jakob had fled his family trade of innkeeping for the musical profession and nurtured a penchant for bad financial investments. Gängeviertel was locally known as the “Adulterer’s Walk” for its active sex trade. The Brahms family lived in a tiny shared house set back from the alley. Swafford describes the scene as “brutal, the kind of thing of which Dickens made a dark poetry.”

Although the family moved two years after Johannes’ birth, the budding composer would find his way back to this darkness in 1846. Before Johannes turned thirteen, Johann Jakob reasoned the boy must provide income from his playing if he was to continue with it. Night after night, he sent Johannes out to play from midnight to dawn at the pubs near the docks in St. Pa uli. The Animierlokale (Swafford roughly translates this as “stimulation pubs”) were waterfront dives replete with sailors and “Singing Girls” (singing, of course, being among the more innocent of their services). Johannes quickly learned the required music by heart and used the piano rack as a place for novels and poetry instead. He tried to block out the rowdy debauchery surrounding him with the writing of German Romantics. Nevertheless, Johannes told a friend later in life that he “saw things and received impressions which left a deep shadow on his mind.” At the same time, he claimed, “I would not on any account have missed this period of hardship in my life, for I am convinced that it did me good.”

Johannes started composing at age eleven. Youthful summers spent in idyllic Winsen provided necessary balm for the wounds of the Animierlokale and proved fertile creative periods though none of his compositions from these summers survive. In 1853, after a smalltime concert tour with Eduard Reményi, Johannes made the fateful acquaintance of Robert and Clara Schumann in Düsseldorf. All of twenty years old and still unpublished under his own name, Johannes left quite an impression on the Schumanns. Robert wrote a glowing article about his discovery in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, a progressive music journal he founded when Johannes was less than a year old:

“I have thought […] someone must and would suddenly appear, destined to give ideal presentation to the highest expression of the time, who would bring us his mastership not in process of development, but springing forth like Minerva fully armed from the head of Jove. And he is come, a young blood by whose cradle graces and heroes kept watch. He is called Johannes Brahms.”

Heavy is the head that wears that crown. Robert Schumann had placed the weight of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn and more on his young protégé. And this was not Schumann’s first prophecy. In Swafford’s words, “Everyone familiar with Schumann’s writings knew about his history with handsome young composers. Famously, none of them had achieved the stature he predicted.” Johannes wrote a letter of thanks to his “Honored Master” but there is no doubt that this proclamation sharpened his already critical nature. “Above all,” Johannes writes, “it obliges me to take the greatest care in the selection of what is to be published.”

With Robert’s mental deterioration and eventual asylum residence, Johannes grew very close to Clara. After Robert’s death, the question of marriage hung unanswered between them. Establishing a pattern he would follow throughout his life, Johannes backed away from the woman he loved and turned to his music for solace. In the twilight of their lives, Johannes requested Clara return all the letters he sent her: “I most earnestly beg you to return them to me, and if I say send them quickly, please don’t think it’s because I’m in a hurry to send them to the bookbinders!”

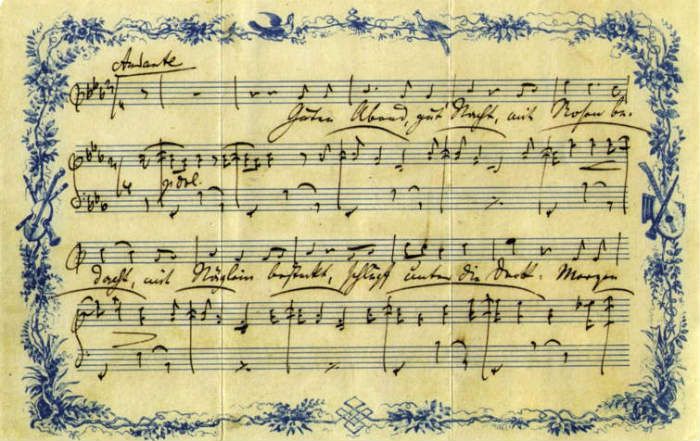

In 1868, established as a masterful composer after the success of Ein deutsches Requiem, Johannes wrote his most famous melody, Wiegenlied or “Cradle Song,” for the second son of a former Frauenchor member, Bertha Faber (née Porubzsky). He composed the song in counterpoint to a Viennese Ländler the young fräulein used to sing to him during his days conducting the women’s choir in Hamburg. In a letter to Bertha’s husband, Johannes wrote, “Frau Bertha will realize that I wrote the Wiegenlied for her little one. She will find it quite in order … that while she is singing Hans to sleep, a love song is being sung to her.” Yes, all quite in order. Associating sex with business transactions and disreputable women seems to have left Johannes with no way of consummating his love for virginal women other than through song. The dark shadow of misogyny cast by this association hung over him to the last.

Perfectionism may have inspired Brahms to great heights as a composer, but it resigned him to tortured lows as a man. Perfect women do not exist. Thus, Brahms frequented brothels and never married.