The New York Philharmonic has developed a digital archive covering its 174-year history, allowing researchers to view data and other information about the approximately 16,000 performances it has put on at that time.

Archivist and historian Barbara Haws, who has been working since the 1980s to build up databases of the records, discusses the collection and takes you on a tour in this podcast.

It begins, quite literally, at the beginning: a program from the New York Philharmonic’s opening performance on 7 December 1842, during its first season. On that occasion, they played Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, and the score used by the conductor and a copy of the program sent out to subscribers are kept in the collection.

The tour takes a look at records from rehearsals from 1875 on which the number of attendances by orchestra musicians were kept. 140 years after the fact, you can find out about who showed up most often to rehearsal, and who was fined for poor attendance. One unlucky New York Philharmonic musician was fined $11 after appearing at only two out of six performances, a large sum in the money of the day.

Another fascinating find is a collection of newspaper coverage produced for the orchestra’s European tour in the early 1930s. A large scrapbook of articles covers newspapers in every U.S. state, so the reader can get an idea of what the media thought of the New York Philharmonic’s performances at the time. Haws explains that the tour was an important milestone for the organization, helping to put the orchestra on the world stage.

As well as opening up possibilities for music enthusiasts to view original scores or get an idea of the most popular pieces performed over a particular period, the data has also been used by broader circles of researchers. Haws talks about a group of sociologists who did a profile of the New York Philharmonic’s subscribers to understand which parts of the city they came from and what their social background was.

With so many different interest groups, the job of Haws and other staff in the archives isn’t so much to decide what is important, but rather to make all of the documentation available to the public. She pointed out that material that may seem mundane or irrelevant could turn out to be extremely crucial for the research or work of someone else.

Haws explained, “partly the reason they kept all this detail is that they were partners, they were a cooperative that managed themselves. So in order to trust each other, they wrote everything down.”

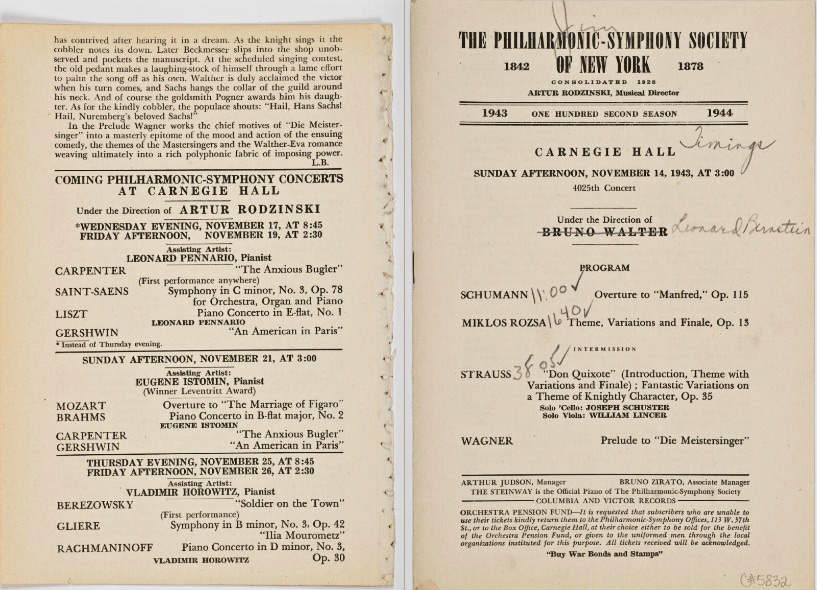

The archive also includes every program since 1842. Mitch Brodsky, who manages the digital archive, told an interview last year that his favorite item was Leonard Bernstein’s score of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, which as well as showing the great conductor’s artistry also contains a “Mahler Grooves” bumper sticker.

It’s now possible for them to track where researchers are based who are engaging with the material, and information reaches many more hands than it formerly would. A Leonard Bernstein score from the opening of the Philharmonic hall has been viewed 25,000 times, which Haws noted would have been impossible in the pre-digital era without totally destroying the quality of the document.

There has, however, been one downside to this. “Here in the reading room at this table, [in the] pre-digitization world, people had to come here to do research. So we would talk. I’m still working on [figuring out] how we replicate that discussion. How do we share? But regardless, more will be known, and it will have greater value than could ever be managed at this very small room and this reading table,” she said.