Before looking further into the title of this article, I feel I should briefly clarify what the terms in the title mean. Commonly in popular music genres, there are elements of that music that are referred to as licks or riffs. Unlike a melody, the term riff or lick usually refers to a small part of a musical phrase that often occurs during an improvised solo. These riffs or licks may only contain repeating notes or a repetitive rhythm but can single out one musician from another, one solo from another solo.

In some cases, there are even characteristic riffs or licks that helps you identify the performer as they tend to use this riff so frequently. It would be utterly impossible to write out every riff or lick that appears in jazz, so I have taken a few choice examples that I commonly use when playing and that I feel are offer a good entry point for further exploration of this almost endless area of possibilities. Ultimately, the limits are in your own imagination.

Jazz Piano Licks & Riffs

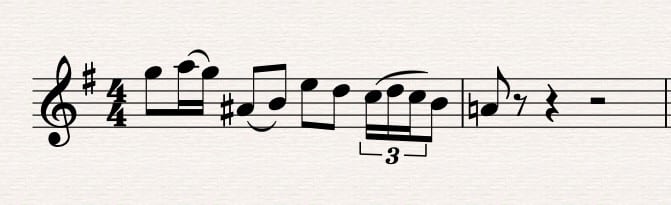

One riff that you may hear in many different types of jazz is the one shown below. This little riff relies on the ‘blue’ note, the D#, to create a colourful twist on an otherwise simple repeating rhythm. It can be played neatly over a great many different chord changes if carefully places and used almost anywhere in a solo.

Along similar lines to the riff above, adding ‘chromatic’ movement to an improvised melody, or an existing melody, works well and is common in jazz. The beauty of a chromatic ‘passing note’ (a note that fills in between other notes), is that it can work over almost any selection of chords. This is also true as the passing note tends not to be one that is lingered on, just slipped into the waiting space, adding a touch of ambiguity to the line. The ‘syncopation’, or off-beat emphasis of this riff also makes it an attractive option.

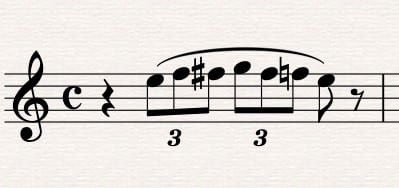

The idea of decorating an existing melody is a good place to start when improvising in jazz. Decorative figures can be thought of as mini-licks and could be chained together to form a longer passage if required. One of the favourites of many jazz musicians that is easy to spot is what I would call the ‘skip’. Essentially, the skip just means adding two quick notes just before the main tone. It is in some ways quite similar to the filling in idea mentioned above but on a smaller, more modest scale. The ‘added’ notes you can see are the A and G, then on beat 4 the C, D, C, semi-quaver triplet. It brings a rhythmic interest to an otherwise quite ordinary phrase.

Below is a lick that is used to great effect in many famous jazz solos. What makes it attractive is the ‘triplet’ lift upwards that compliments the swung quavers and projects the solo forward. You will also notice that the riff begins on the 9th degree of the D minor scale and then effectively plays an arpeggio figure that serves to quickly outline the harmonic movement of the piece often referred to in jazz as the ‘changes’. This riff could be used successively to create a longer pattern or played on different of the bar to blur the clarity of the four-four time signature. You could also extend the triplet idea to perhaps encompass a greater range or two or even three octaves before bringing the phrase back down.

This was one of the first licks I heard when I was introduced to Dixieland Jazz. Whilst many of the improvisations from that style of jazz rely heavily on arpeggio figurations this charming addition is a short chromatic embellishment that works well in almost any setting, but particularly for fast tempo pieces. The placement of the riff on the second beat is also significant as it does what jazz does so well, and pushes the feeling of the main beats (one and three), just momentarily out of focus. It is perfectly possible however to play this riff where ever you feel it fits in but always keep in mind the rhythmic movement of the tune.

A familiar trait of many riffs and licks is a repetitive rhythm. On the surface of that description, you could interpret it as simply a row of repeating crotchets or quavers that in practice do not present anything of genuine interest in an improvised solo. In the example below, what you have is a riff that flows over a two-bar series of chord changes. The notes used here are almost as repetitive as the rhythm but what is appealing about the riff is the syncopation. True the riff begins unlike others on the beat, but then the rhythmic emphasis is quickly changed. If repeated perhaps three times rather than two, with the final quaver entering on the last half of the fourth beat, then the riff has added interest.

The type of jazz that came to be known as Bebop produced a catalogue of riffs in its own right. If you have ever had the opportunity to listen to Bebop you’ll quickly realise that the style is incredibly complex and technically difficult. Bebop players were able to perform some of the most intricate and ground-breaking solos you will ever hear, pushing the harmonic and rhythmic boundaries of the genre. A favourite creation of the saxophonist Charlie Parker was the riff below. It is partly chromatic at the start then it moves downwards before returning to emphasise the 9th degree of the F scale. The inclusion of the E flat also brings a bluesy feel to the riff that adds interest.

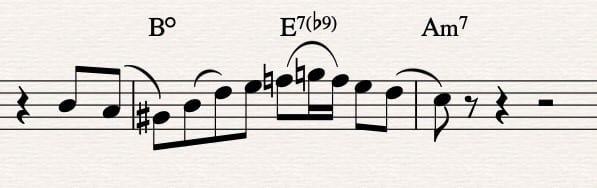

The last riff for this article is another one from the bebop catalogue. It is a riff favoured by many a jazz performer because is it useful over what is known as the ‘turnaround’. This is a progression of chords, usually ii – V – I, that close a section or lead onto another section or sequence. Like many of the previous riffs its shape is a rise and a fall that outlines the initial chord pattern then heads towards the flattened ninth of the E scale. This is a truly useful and stylish riff to learn and try out over the full key range of turnarounds.