The first is that the vast majority of famous composers who committed crimes almost certainly got away with it. Until the mid-19th century, the criminal justice system as we have come to know it in the industrialized West did not exist. The first penitentiary (Eastern Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and the first modern police force (the London Metropolitan Police) were both founded in 1829—and even they did not enforce, and were not expected to enforce, a consistent rule of law that ignored a person’s social role. As you’ll see below, the nobility and those they favored could quite literally get away with murder. Add in the fact that most crimes were unsolvable to begin with (fingerprints weren’t admissible as evidence until 1905, for example), and it’s reasonable to assume that the vast majority of crimes went unpunished, especially if they were committed by traveling artists with upper-class connections.

The second is a simple matter of cause and effect. Composers who are arrested for committing a serious crimes don’t generally become famous; that’s the sort of thing that interrupts a career.

And the third factor is narrative: for readability’s sake, I’ve mostly left out political prisoners. The same connections to the nobility that might make a composer invulnerable to an ordinary criminal charge can become extremely inconvenient, and sometimes fatal, in times of political upheaval; when this involves charges of treason or sedition, it seems silly to treat those charges as crimes simply because the political winds have changed. Only two of the composers mentioned below were prisoners of conscience, but there were many, many others; in 1794 alone, the composers Pascal Boyer, Jean-Frédéric Edelmann, and Jean-Benjamin La Borde lost their lives (and, more specifically, their heads) to the guillotine.

There would be something especially obscene about characterizing the victims of fascist regimes as criminals under any circumstances, even if they were executed on named charges. An article detailing great composers who lost their lives in the early 20th century to the Axis Powers because they were deemed guilty of treason, sedition, or related charges could easily fill a volume, never mind a short article, but you won’t find them here.

What you’ll find instead are characters like…

Carlo Gesualdo (1560-1613)

Nationality: Italian.

Best known works: His brilliant but unsettling madrigals sound like modernist compositions, written centuries before their time.

Crime: Double homicide; Gesualdo brutally murdered his wife and her lover in 1590. Some sources accuse him of later murdering his father-in-law and his youngest son, but this is most likely a later embellishment.

Legacy: While Gesualdo escaped prosecution (as he was a member of the nobility), he did nothing to cover up his crimes—and if he’d tried, it’s likely that one of his dozens of accomplices would have given him away. Subsequently, Gesualdo is better known today as a killer than as a composer. Werner Herzog’s documentary Death for Five Voices (1995) examines the gruesome mythos surrounding the murders and their aftermath.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Nationality: German.

Best known works: Too numerous to mention, but the opening notes of his “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” (BWV 565) have become a universally recognizable token for golden-age horror films—probably because they were used during the opening credits of Paramount’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931).

Crime: Requesting termination of a contract. In 1717, Bach asked the Duke of Weimar to release him from employment so that he could pursue other opportunities. The Duke responded by ordering Bach’s arrest, and he spent the next month in jail. While attempting to get out of a contract is not generally considered illegal, the fact that Gesualdo couldn’t even be prosecuted for a double murder already tells you that in the 18th-century European aristocracy, a crime was pretty much whatever a member of the nobility said it was.

Legacy: Bach is generally regarded as the greatest classical composer of his era, and very few people even know he was arrested. Meanwhile, the duke who had him imprisoned was of so little historical significance that I don’t even feel obligated to mention his name.

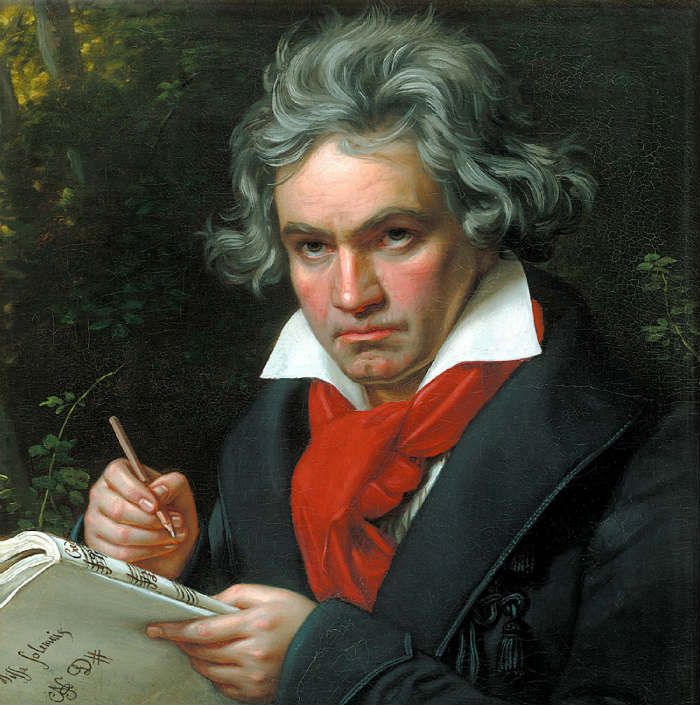

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Nationality: German.

Best known works: Too numerous to mention, but the first movement of his Fifth Symphony is especially hard to miss.

Crime: Prowling and vagrancy. “Mr. Commissioner,” a Viennese constable said, “we have arrested somebody who will give us no peace. He keeps on yelling that he is Beethoven; but he’s a ragamuffin, has no hat, an old coat … nothing by which he can be identified.” After checking with a local musician, the commissioner was able to verify that the dirty, middle-aged man who had been picked up for wandering around Vienna looking in people’s windows was, in fact, who he said he was.

Legacy: Fans of Beethoven know that he grew more eccentric with age, and many cite this story as evidence. Far from harming his legacy, Beethoven’s arrest cemented his reputation as an unorthodox genius.

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Nationality: Austrian.

Best known works: Schubert was a versatile and prolific composer whose entire body of work is widely performed and appreciated to this day, but he is probably best known for his song cycles, most notably his Wilhelm Müller adaptations Die Schöne Müllerin (1823) and Winterreise (1827).

Crime: Attending an illegal student gathering, and using “insulting and opprobrious language” towards the police after they arrested his friend. In 1820, Schubert and the promising young Austrian poet Johann Senn were suspected of organizing against the Austrian government in general, and its recent crackdown on free speech in particular. Schubert was released almost immediately, but Senn spent over a year in prison and his group was shut down.

Legacy: The arrest is mentioned in most biographies of Schubert, but because he was functionally a victim of political oppression it doesn’t reflect poorly on him; the proto-fascism of the Austrian secret police has not aged so well.

Ethel Smyth (1858-1944)

Nationality: British.

Best known works: Smyth’s opera The Wreckers (1906) was probably her most popular composition during her lifetime, and her March of the Women (1911) was an important suffragist anthem, but her instrumental works are more often performed today.

Crime: Vandalism as civil disobedience. Smyth was one of the more than 100 English suffragists arrested in 1912, and served two months in prison for allegedly throwing rocks at the window of a conservative politician’s residence. She took the opportunity to teach all of her fellow inmates how to perform “March of the Women,” and is said to have conducted the impromptu prison choir with a toothbrush.

Legacy: Smyth’s arrest only strengthened her resolve, and the movement she helped lead decisively won the argument when Britain passed the Equal Franchise Act in 1928.

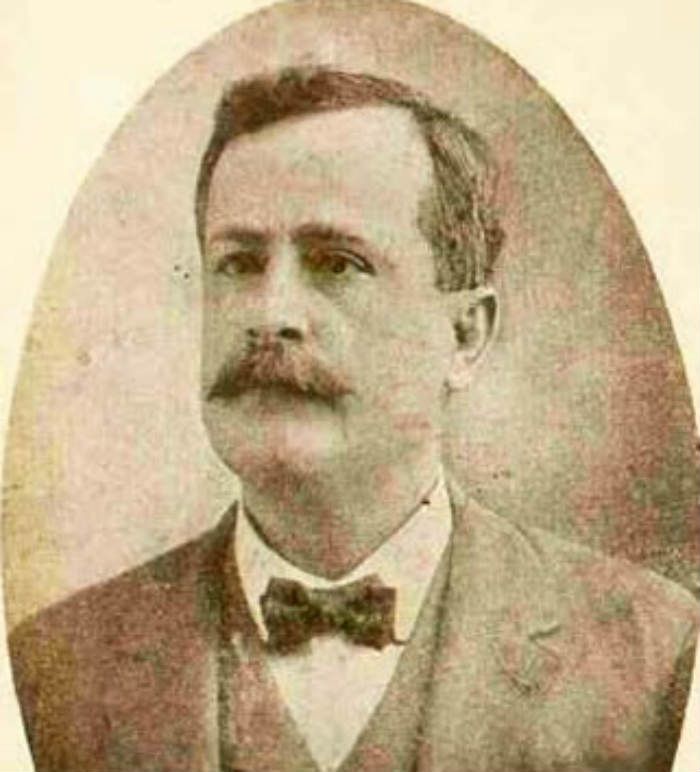

Pietro Mascagni (1863-1945)

Nationality: Italian.

Best known works: Mascagni’s masterpiece was the opera Cavalleria Rusticana (1890), whose most famous movement—the symphonic intermezzo—will be familiar to many listeners, both as a common melody for “Ave Maria” and as the closing music for The Godfather Part III (1990).

Crime: Embezzlement. While on a U.S. tour, Mascagni was arrested in 1903 after refusing to give his manager, Richard Heard, $5,000 that he claimed was owed. Mascagni was later acquitted on all charges; Heard, who had told Mascagni that written contracts were not used in the United States, had ostensibly tried to use the U.S. criminal justice system to extort money from him.

Legacy: Mascagni, who never got the hang of U.S. business practices, suffered another round of lawsuits a few years later before leaving the country for good. The vast majority of historians and critics seem to judge Mascagni primarily by his Cavalleria Rusticana, which is still widely performed to this day; those who dig deeper into his biographical history are unlikely to be especially horrified by the specious embezzlement charges, though Mascagni’s later enthusiastic support for the Mussolini regime (while perfectly legal) is harder to defend.

Rodolfo Campodónico (1866-1926)

Nationality: Mexican.

Best known works: Campodónico is best remembered for his waltz “Club Verde,” which is still popular.

Crime: Inciting a riot at a 1913 concert by…well, nobody’s quite sure. His granddaughter attributes the riot to the popularity of “Club Verde,” arguing that local officials locked Campodónico in prison to protect him from a mob of frenzied fans, but a local newspaper attributes his imprisonment to his decision to play an illegal and politically charged march (“Viva Maytorena”) twice after his audience interrupted the first performance. It’s possible that both accounts are partly true—maybe the audience just wanted to hear “Club Verde,” and Campodónico grew so frustrated with their impatience that he played “Viva Maytorena” twice. Anyone who has ever heard an audience member shout “Freebird!” at a rock concert should be able to relate. (Tania Zelma Chavez-Nader has examined the controversy in some depth in her 2009 doctoral dissertation on Campodónico, and it makes for a fascinating read.)

Legacy: Campodónico was never charged, and the incident is seldom mentioned outside of scholarly literature.

Henry Cowell (1897-1965)

Nationality: American.

Best known work: The powerful and unsettling “Tides of Manaunaun” (1917) will probably always be Cowell’s best-known composition, but he wrote it at the very beginning of a productive and critically acclaimed five-decade career.

Crime: Consensual sex with an adult of the same gender. In 1936 Cowell became the first person ever successfully charged under California’s section 288a, which mandated a prison sentence of up to 15 years for any act of “oral copulation.” He served four years in San Quentin State Prison, and was pardoned in 1942. It is worth noting that Cowell was never convicted as such; he refused counsel, pled guilty, and threw himself on the mercy of the court, and the court responded by showing a remarkable lack of mercy.

Legacy: Other than Gesualdo, no composer’s legacy has been more profoundly affected by an allegedly criminal act than Cowell’s—despite the near certainty that more than half of the composers in the Western canon engaged, at some point, in an act of “oral copulation.” “Many people begin a conversation about Henry Cowell by telling me why he spent four years in San Quentin,” the Juilliard music historian Joel Sachs lamented in 2012. “Although I prefer to dwell on Cowell’s enormous accomplishments as a composer, theorist, performer, and educator, there is no need to run from the matter.”

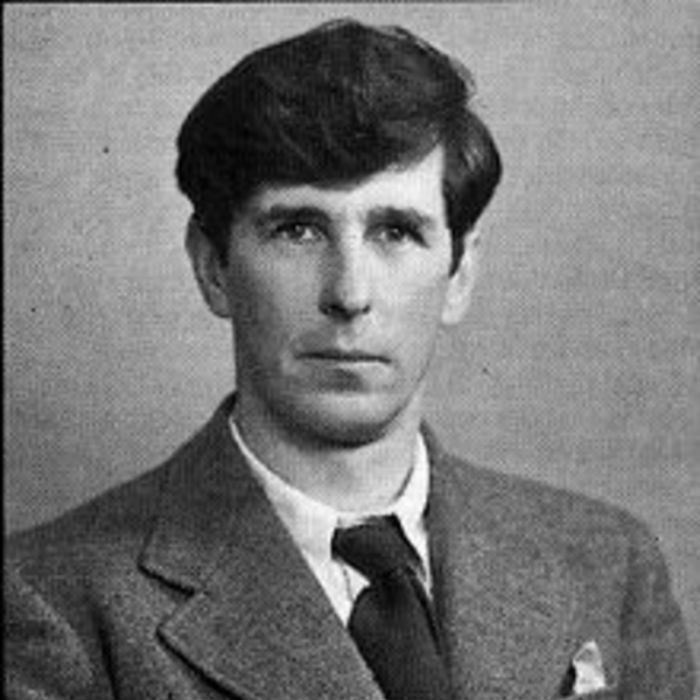

Michael Tippett (1905-1998)

Nationality: British.

Best known work: His lengthy, complex oratorio A Child of Our Time (1941) is his best known work.

Crime: Conscientious objection to military service. A committed pacifist, Tippett had pledged to resist service during World War II in any capacity, be it as a combatant or non-combatant. For his decision, he served two months in prison.

Legacy: Because A Child of Our Time was such a forceful indictment of fascism, nobody could have mistaken his conscientious objection for Axis sympathies. The public reaction was that Tippett was indeed a pacifist, and that his conscientious objection was to be accepted as legitimate and principled. His critical reputation as a composer seems to have survived the scandal completely unscathed; he was even knighted in 1966.

Glenn Gould (1932-1982)

Nationality: Canadian.

Best known work: Gould was far better known as a pianist than as a composer (his performances of Bach are still regarded as definitive), but his cheeky “So You Want to Write a Fugue?” (1963) went viral (to whatever extent something can go viral in the pre-Internet era) and introduced a new generation to the sheer fun of polyphony.

Crime: Suspicion of vagrancy. Multiple credible sources report that Gould was once arrested in Sarasota for sitting on a park bench in the summer while wearing a hat, coat, and gloves, something he regularly did regardless of the weather.

Legacy: Gould’s unusual personality traits have often been regarded as signs of eccentric genius at best and pretentious displays at worst, but many scholars now suspect that Gould may have had autism. This could help to explain his aptitude for Bach, his preference for playing the piano while sitting in an old chair that his father customized for him, and his habit of wearing weighted fabric. Whether critics (or the Sarasota PD) understood his methods or not, one thing is clear: they worked.