When I read the word nationalistic my mind instantly shifts toward the music of Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975). The reason for this is not only a great admiration for the work of Shostakovich but also because it represents a type of music that is overtly nationalistic.

An additional consideration is that the music of Shostakovich is far more than nationalistic. It has hidden layers that should not be overlooked whenever a close examination of nationalistic music occurs.

Characteristics of Nationalistic Music

Whilst Shostakovich does not directly include the use of traditional folk melodies, closely associated with nationalistic music, in his work, he composed music to the orders of the Russian Communist Party: namely, Stalin.

Shostakovich’s relationship with the Communist Party was never an easy one, but as a respected, high-profile composer who was born and raised in Russia, he had no option but to comply.

This became a constant and terrible theme that haunted Shostakovich his whole life. He had to match his artistic ambitions with the expectations of the State.

To give an example of Shostakovich’s approach to this terrifying dilemma, begin with the Fifth Symphony (1937).

In this work alone, we hear what on the surface appears to be a deeply Russian work full of patriotism and pathos. Dig a little deeper and listen carefully and you will hear that the music is highly satirical.

Shostakovich, through his ingenious orchestration, and intricate harmonic structures manages to support and slur the regime in a single orchestral piece.

Music that can be more closely considered to be nationalistic, often contains characteristic rhythms, harmonies, and instruments that are associated with any given country. It is also not uncommon for these pieces of music to include, develop or just exploit, traditional folk tunes.

The key difference between this type of nationalism and the music along the lines of Shostakovitch is that it also includes political influences or even propaganda.

On the lighter side of nationalism, we can include composers like Frederick Chopin (1810-1849). Chopin has been famed for the exceptional selection of piano music he composed in his brief lifetime.

This output includes ‘Nocturnes’, ‘Preludes’, ‘Concertos’, and the famous ‘Etudes’.

Where we hear Polish nationalism more clearly perhaps is in his collection of Mazurkas and Polonaises. There are somewhere in the region of 59 Mazurkas and around 23 Polonaises.

In the Mazurkas, we truly witness the influence folk music had on Chopin’s compositions. Even as a child Chopin would listen to folk bands and learn to sing folk songs. They embedded themselves into his music.

In the Mazurkas, we can hear Chopin recalling the instrumental sounds of folk bands, borrowing the dance rhythms and melodic features that saturated his early life and coloured so much of his later music.

In the grand operas of Richard Wagner, there exists a blatant dominance of nationalism. All of his colossal operatic works centre on Teutonic legends that extol and amplify everything that he felt was quintessentially Germanic.

Considering the epic ‘Ring Cycle’ or ‘Tannhäuser’ and ‘Tristan and Isolde’ would be a fine place to begin.

Wagner viewed these operas not only as a vehicle for expressing his cultural and philosophical values but as an open invitation to the new generation of Germans to unite under one banner.

Unfortunately, the Nazis understood the power inherent in Wagner’s music and exploited his music to terrible ends.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), along with composers like Edward Elgar and Gerald Finzi is often thought of as typically British composers.

Certainly, amongst the British pastoral composers, these gentlemen stand out but it is Vaughan Williams whose dedication to English folk music perhaps singles him out for special attention.

In his own words, he expressed his feelings beautifully; “The art of music above all the other arts is the expression of the soul of a nation”. For most of his life, Vaughan Williams devoted himself to collecting and collating folk music from all over Britain.

The influence and power of this traditional national music threaded their way through numerous compositions by the composer. It coloured and carved out his musical voice into an iconic musical landscape that is almost unparalleled in intensity and beauty.

This seems particularly true of his symphonic works. In a similar way to the music of many nationalist composers, the works of Jean Sibelius embody the country in which he was so deeply invested. In the case of Sibelius, it was Finland.

Through his upbringing and schooling, Sibelius developed a deep interest in the folklore of Finland. His passion for the country was clear when even during Germany’s invasion of Finland during the Second World War, Sibelius refused to abandon his beloved country.

The very essence of Finland permeates so much of Sibelius’s music. The rhythms, melodies, and spirit of the country saturate his scores. Possibly the most nationalistic work is ‘Finlandia'(Op.26).

Keeping in mind that Russia still had a firm grip on Finland at the time this piece was composed (1899), it makes sense that this commissioned work was in support of the freedom of the Finnish Press.

In only eight minutes Sibelius rouses a sense of burning nationalism and the fight for the county he loved.

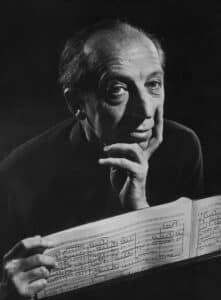

The work of American composer Aaron Copland is often closely associated with Americana.

From ‘Rodeo’ and ‘Billy the Kid’, through to ‘Fanfare for the Common Man’ and the ‘A Lincoln Portrait’, Copland’s music, perhaps even more than that of Leonard Bernstein, captures the spirit of the old west and the new America.

‘Fanfare for the Common Man’ and the ‘Lincoln Portraits’ are most obviously patriotic in intent.

The Fanfare was commissioned by Eugene Goossens in 1942 and aimed at boosting national morale at what was about to be an increasingly troubled time. Copland brilliantly scored the work for brass and percussion.

The composition is rousing, and majestic and has been used for many subsequent National Events.

Equally, ‘A Lincoln Portrait’ goes one step further in terms of nationalism. It includes a recitation of President Lincon’s words that were famously performed by Henry Fonda.