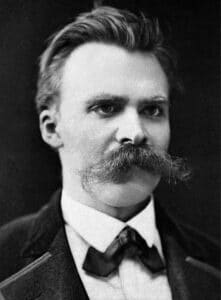

Let’s plunge into this title with a fleeting glance at Friedrich Nietzsche. Why am I electing to evoke a dead German philosopher initially, Nietzsche provides us with a thorough analysis of these two pillars of the Greek world and art in his book titled ‘The Birth of Tragedy’.

Apollonian Vs Dionysian Music

Apollo and Dionysius were Greek Gods. Nietzsche felt these two opposites were important to us as human beings and had a rightful place in art. Apollo, as you may already know, was the God of the sun. He was also the deity credited with withholding the truth and representing logic.

In contrast, Dionysus was the polar opposite. He was the God of festivals, wine, and even insanity and chaos. What Nietzsche examined in his book was how the Greeks, in particular, could fuse these two personality types, characteristics, and drives into their art forms.

What we have in Dionysus and Apollo are in one sense, two sides of the same coin. Whilst they oppose one another to a certain extent, they also rely on each other to ensure balance.

If for example, you were to have a piece of music that was purely Dionysian, could it form a coherent composition? What would such a hedonistic, drunken, chaotic piece sound like?

Equally, a composition that took Apollonian characteristics for its basis and did not include a Dionysian element could be highly organised, rational, and pure but would those ingredients be enough?

Perhaps we could consider genres of music such as Punk Rock as exhibiting a Dionysian edge whereas the later works of Anton von Webern, crystalline, logical music.

The fact is that both of these contrasting musical examples also embrace the opposite features too, just in different proportions.

Returning to Nietzsche for a moment, it is interesting to note that he was a musician and composer. Throughout his, Nietzsche was plagued by terrible, all-consuming migraines.

By the age of only forty-four, Nietzsche had suffered a stroke and a mental breakdown that rendered him almost completely physically incapable and with dementia. (Incidentally, Nietzsche’s father had died of a stroke at the age of only thirty-six).

Remarkably, even after Nietsche had endured the stroke and breakdown he was still able to perform much of the music he had learned in his youth, in particular Beethoven.

What I am illustrating is the importance of music to Nietzsche the performer and composer, and how critical his examination of music was.

In terms of a balance between the opposing Greek Gods in music, Nietzsche expresses clear favour with music needing to be Dionysian.

Apollonian music as far as Nietzsche was concerned ‘degraded music into an imitative counterfeit of phenomena’ and rendered it absent of its ‘mythopoetic power’.

The mythic part of this argument is essential to Nietzsche as he views it as a ‘unique example of universality and truth’. Dionysian music Nietzsche suggested allowed humans to connect with the universe and nature in a way that the Apollonian could not.

With this philosophy firmly in mind, Nietzsche heralded the music of Richard Wagner as profoundly Dionysian. He adored Wagner’s music and this is richly apparent in Nietzsche’s first published work, ‘The Birth of Tragedy’.

If you are familiar with Wagner’s music you will know he is a composer of immense operas with the Ring Cycle at the centre of his impressive output.

This opera cycle along with others Wagner composed often draws on mythology, so there is the first parallel with Nietzsche’s concept, but it goes further and deeper.

There is a hedonistic, passionate, strongly yearning quality to Wagner’s music. It is completely indulgent, opulent, and tragic. These qualities are apparent quite quickly in the music of Wagner and it is perhaps understandable that Nietzsche came under his powerful spell.

What we should not overlook, however, is the Apollonian traits in Wagner’s music that cement together the more immediate Dionysian.

Wagner’s music for instance is not in any way chaotic or disorganised. It is not the product of whim and whimsey but sophisticated and intimately structured.

Everything about Wagner’s music is calculated on every level of perception and beyond. Even though the Dionysian attributes are in the compositions, so too are the Apollonian.

If we can accept this in Wagner’s music then we also draw closer to aligning with Nietzsche when he argues that it is a balance of these two natural impulses that creates great art.

In some ways what we hear in numerous musical examples is damnation and redemption; chaos and order; ecstasy and pain; moderation and indulgence.

In a similar way to the Chinese philosophy of Yin and Yang, Dionysus and Apollo represent humanity with both our dark and light sides.

It follows then that as humans create music these living facets of the human psyche will become an inseparable part of any artistic endeavour. I would venture so far as to say this is evident in all art forms to varying degrees that then appeal to or disgust those listening, watching, or possibly creating art.

There is of course an inherent danger of trying to classify music in respect of these two Ancient Greek terms. They are of use to us to perhaps recognise our fallible human qualities that bubble through the textures, colours, and movement of the arts.

But to view music, or any art form solely as Dionysian or Apollonian would be to greatly limit our perceptions. This would be especially true, I feel, if we also sort to only discover a single one of these characteristics in the vast galaxy of music available to us today.

Both in the creation of music and the reception of musical performances, we will naturally be drawn toward certain features that can broadly be attributed to Dionysus and Apollo. It depends on so many factors like mood, venue, and performance and can even change from one hearing to another.

What we may be able to agree on is that the message from the Ancient Greeks, who eventually gravitated in the direction of Apollo, is that each of us and all we create both crucially exist side by side.