Praeludium and Allegro is one of the most popular works in the traditional violin repertoire and certainly a dream piece for many aspiring violinists for a variety of reasons.

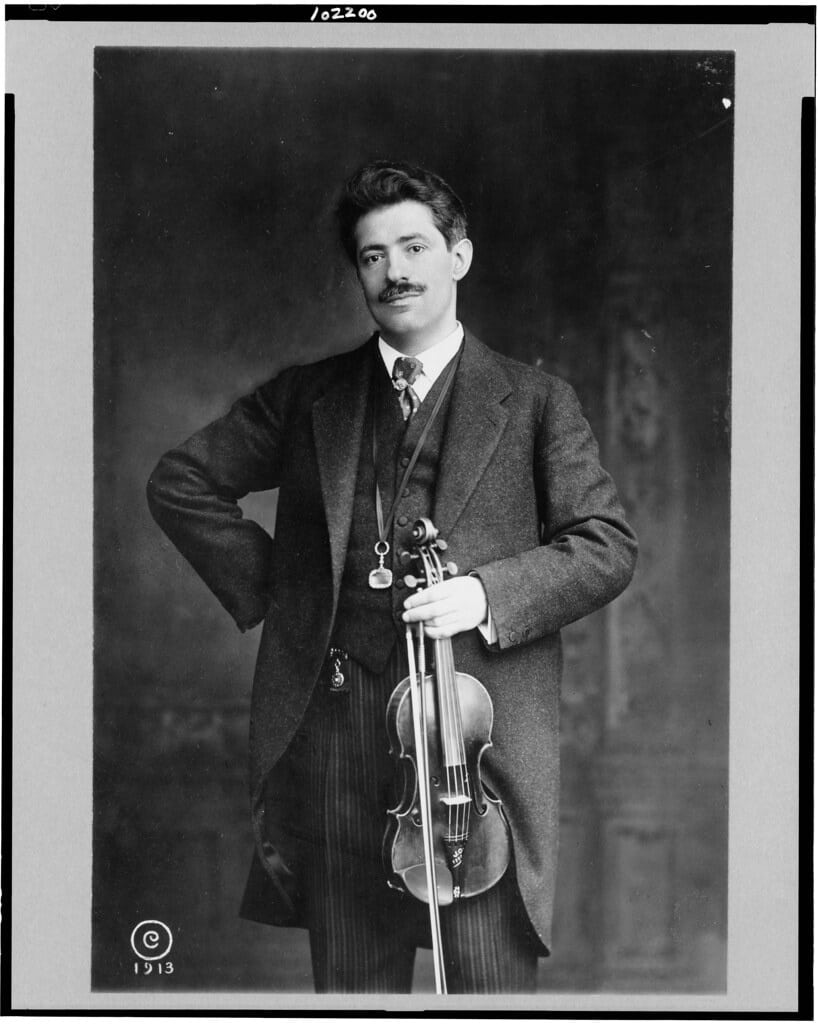

Composed by Fritz Kreisler – one of the most famous violinists who ever lived – and published in 1905 along with many other pieces of Kreisler, it soon gained popularity in the whole violin world.

What is so special about this piece and what skills are necessary for a violinist to play this piece? Keep reading and you will find the answers!

Kreisler’s Praeludium and Allegro Difficulty

Praeludium and Allegro was originally attributed to Gaetano Pugnani – a violinist from the 19th century – by Kreisler himself.

The practice of attributing pieces to famous but non-living composers in the previous centuries was not uncommon – it was a way that composers could either pay hommage to the great masters or simply a way to draw attention to their freshly composed pieces.

The latter was Kreisler’s intention when he attributed many of his pieces to Pugnani by saying he found a bunch of old violin manuscripts and adapted them at his own will.

Indeed, the world-class violinist could draw the attention to his pieces and they soon reached all corners of the world as the publishers got so interest in his works.

Kreisler himself was responsible for making his pieces so popular as he would often perform them as encores during his concerts, leaving the audiences bewildered by his beautiful and ear-grabbing melodies.

Soon other violinists started incorporating his works to their repertoire and many pedagogues noticed these piece should be a must for every aspiring violinist.

What makes Praeludium and Allegro an essencial during the learning process is the fact that it requires the violinist to get to know the entire violin fingerboard and its positions, and also to be able to shift from one position to another very quickly, with a clean sound, without losing confidence but keeping a beautiful sound.

For example, to play the initial section of the Praeludium the violinist must keep a confident and energetic bow stroke in every note while shifting constantly from one position to the other, as the shifts happen at every few notes.

Moreover, the melody should be well phrased otherwise it will simply sound like a sequence of repeated notes and patterns that lack absolutely any musical interest.

The second section of the Praeludium, however, deals with the ability of phrasing and knowing how to “rubato” well.

For those who are not familiar with this term, it simply indicates a certain freedom that the violinist must have regarding the rhythmical aspect of the song in order to make it sound less mechanic, but persuasive with a singing quality.

The art of the rubato itself is already a difficult aspect of the technique, as it can not usually be trained so objectely and each violinist is free decide how much freedom he or she wants to take in order to sound more persuasive and deliver their musical message to the audience.

The second part of the piece – the Allegro – explores speed, coordination and dexterity of fingers, i.e, skills thst are part of the daily practice of every violinist. This section can, thus, be regarded as an etude for the left hand and also for bow coordination.

The slow practice of it will certainly take any violinist to go one step above in all aspects of the technique in a matter of weeks.

The final part of this piece can be challenging for many younger violinists because it contains many chords – three of four notes that must sound simultaneously.

String players know that chords are one of the most difficult aspects of the right hand technique.

To get a clean, powerful and yet beautiful sound during them is not an easy task, but must be a goal of every violinist as it improves the violinist’s control over the bow.

One if the reasons why this piece can be a shortcut for the learning process is the usage of patterns throughout both movements. We know that brains learn faster after identifying patterns and sequences.

It also means that the violinist will learn and memorize the piece faster and be able to practice and play without looking at the music, but rather focusing on the visual practice of the study – observing the behaviour of fingers and bow and fixing right away.

The third reason why this piece is so appealing to the ear and pleases every violinist is because its melodies are quite simple.

The opening of the Preludio, for example, alternates between the notes “e” and “b” for some bars, becoming slowly more elaborate, while the rhythm remains exactly the same, allowing the violinist to really focus on one aspect of the technique of a time.

For this piece, it means that the violinist will not need to worry about complex rhythms and will focus on one technical aspect of a time: shifting, slurs, bow coordination, agility, etc.

We have so far described how this piece can help aspiring violinists to reach an upper level of playing. But when should this piece be introduced to their repertoire and which skills they must have mastered before learning this piece?

The answer is quite simple. After they have a basic knowledge of the first few positions, satisfactory bow control and good intonation. In terms of years, this can vary a lot.

For serious students this piece can be already introduced in the second year of playing while for some others it may take three or four years of practice. And how long does it take to learn this piece?

It also depends on how confident each student is in each technical aspect. While for some it will take about a month, for others it may take two months or more of daily practice.

If it is taking too long, perhaps the student is not ready yet for this piece but can be introductory pieces that will help them gain more confidence in their playing.

As a conclusion to this article, here is a list of YouTube links to performances of Praeludium and Allegro by some of today’s most famous violinists, hosted in their official YouTube channels:

Itzhak Perlman

Augustin Hadelich

Joshua Bell

They are all playing the allegro too FAST. Its called allegro MOLTO MODERATO. At M=125 and above the piece sounds like a mere exhibition piece to show off with. Actually its just as hard to play musically at M=85/90, and sounds much more charming, as charming and melodic is what is wanted in this piece……is there a recording of this by Kreisler himself? If there is, and he is going super fast then I must eat my hat and back off!!