In modern music, E♭ and D♯ are the same note (s) on paper and in sound, just spelled differently. But E♭ and D♯ are also two distinct notes before equal temperament arrives on the scene.

DISCLOSURE: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning when you click the links and make a purchase, we receive a commission.

Is E Flat the Same as D Sharp

We’ll examine the ‘Yes’ part of our answer first before we delve into the ‘No’ part of our answer (which is a lot more complex).

When E Flat Is the Same as D Sharp

When you spell a note enharmonically, that is the same note spelled differently. But, because we can write notes with different names doesn’t mean we should do it for the fun of it.

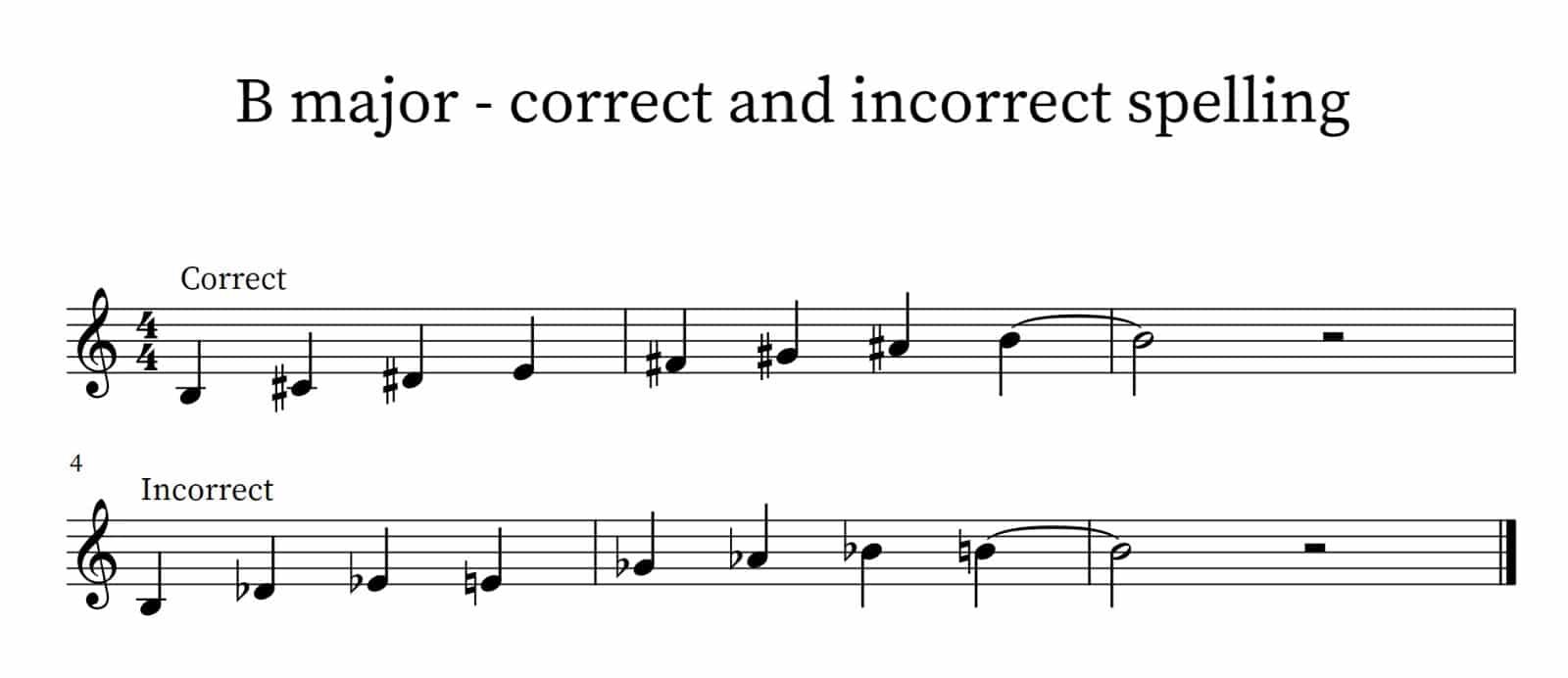

Suppose you spell a B major scale the following way: B, C♯, D♯, E, F♯, G♯, A♯, B. If you were to spell it as B♮, D♭, E♭, E♮, G♭, A♭, B♭, B♮, it would sound the same, but it is a lot harder to read and doesn’t make ‘sense’ within the established rules of Western music theory.

You’ll probably also lose marks on a theory exam. We can illustrate the point below:

As you can see, reading a B major scale written with flats is quite challenging but not impossible. Context plays an important role as well.

If you read a piece in B major, you will expect to see a D♯; in E minor, you’ll also expect a D♯ because it is the raised seventh step of the scale.

But, sometimes, a composer will break the accepted rules and use enharmonically spelled notes for a particular function. You can watch an example in the video to see how Brahms used enharmonic spelling to lead the music back to B minor.

Other times, composers will also use D♯ instead of E♭ as a courtesy to musicians to make reading the music more accessible.

Other times, especially in more modern music where no key signatures are used, a composer may choose to present either D♯ or E♭ depending on the overall context of the music.

When E Flat and D Sharp Are Different Notes

Ethan Hein explains why D♯ and E♭ are distinct notes in this thorough analysis.

Since introducing the keyboard, instrument builders, composers, and theorists have wrestled with precisely how to split an octave interval.

We tune most current organs and pianos under an equal temperament method, which divides the octave evenly into 12 distinct pitches or semitones.

However, most equal temperament intervals are far from mathematically pure. We don’t notice this since we’ve heard equal temperament keyboard instruments since we were children.

Pythagorean was the most popular tuning in the early medieval period, in which fifths are mathematically pure. However, in the late medieval/early Renaissance period, musical tastes shifted, and the third interval became popular.

The issue is that if you start on C and tune four mathematically pure fifths in a row upwards, the resulting E will be exceedingly discordant (C→G, G→D, D→A, and A→E).

To address this, instrument makers shortened (lowered) the fifth by a division of an interval known as the syntonic comma (which equals 21.50 cents; for comparison, in equal temperament, there are 100 cents between each half step—these are tiny alterations that make a significant impact!).

This tuning system becomes very involved, and we’ve linked some resources for you at the end.

The archicembalo has a D♯ and E♭ key and an E♯ and B♯ key. Nicola Vicentino invented it in 1555 to experiment with his theories about tuning and temperament.

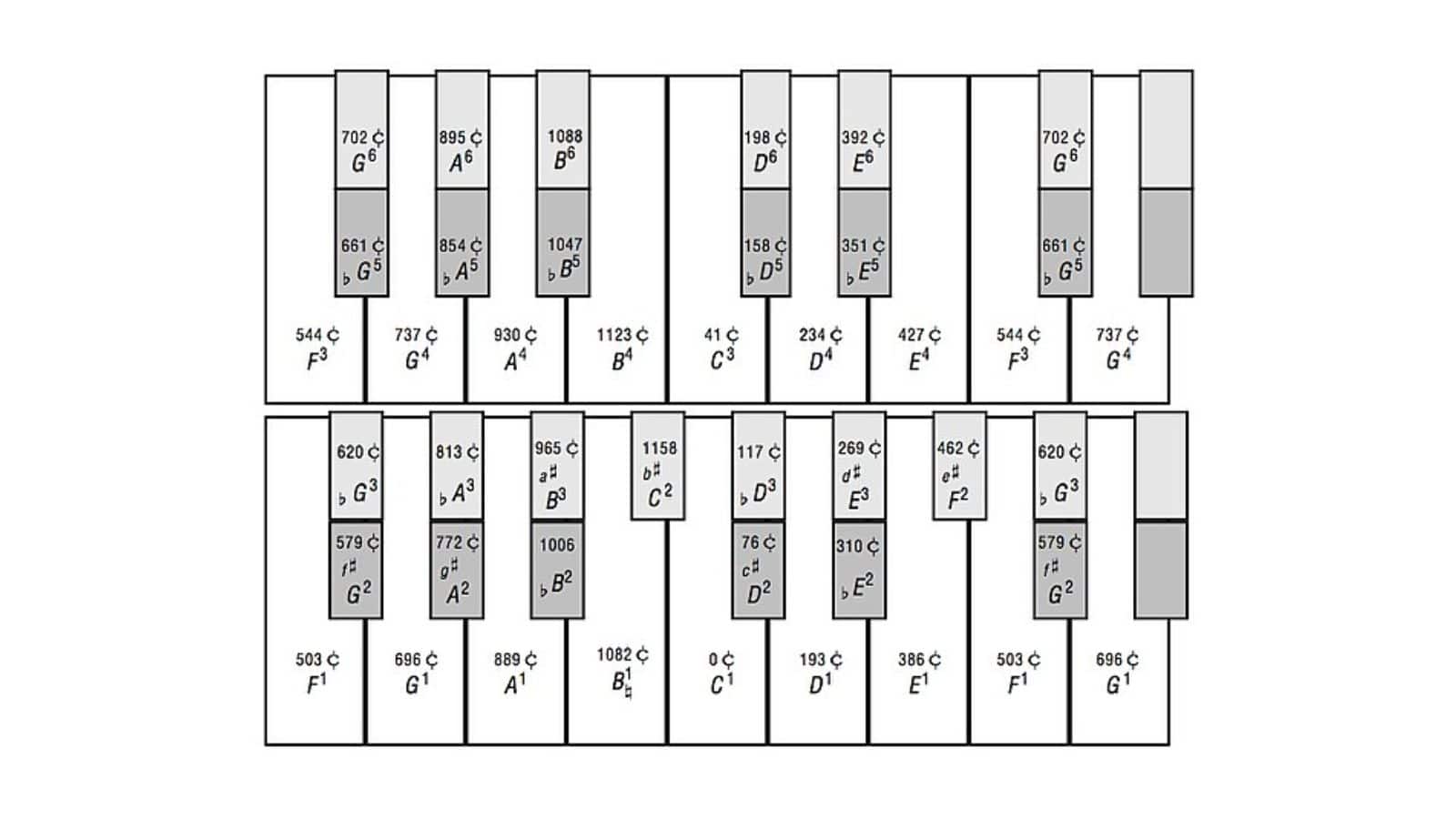

The white keys are identical to those seen on any standard keyboard. Except for D♯ , E♭, and A♯ and B♭, the black keys are divided into two sections: sharp and flat. The lower manual has 19 quarter-comma-marked keys with split black keys.

In contrast, the top manual has duplicate keys without E♯ and B♯ and is tuned a quarter comma higher. As a result of the two manuals playing at different pitches, we have 36 distinct pitches per octave. This approach is known as modified just intonation.

Johannes Keller explains how the arciorgano works (here’s a video of the organ version of the arcicembalo). For every key on the lower manual, a fifth above it on the top manual will be pure.

In practice, if you wanted a ‘pure’ D major chord, you’d play D and F♯ on the bottom keyboard (which is already pure due to the quarter-comma meantone system).

The interval of a fifth (between D and A) is flat by a quarter comma in quarter-comma meantone; since the upper keyboard is tuned a quarter comma higher, you’ll play the A(+) on the upper keyboard.

Minor thirds are the same; they are a narrower interval than pure. You’d play the D on the lower manual and the F(+) and A(+) on the higher manual to play a D minor chord in just intonation. As a result, starting with a root on the lower manual, you can play any triad in just intonation.

Vicentino characterizes the arciorgano as an instrument with all perfect consonances, capable of achieving just intonation sound qualities without the difficulty of the syntonic comma. To summarize, it sounds like just intonation without the syntonic comma.

Caspar Johannes Walter explains composers probably wrote it on these instruments if you see G♯ and A♭ (or D♯ and E♭) in an Italian chromatic work from this period (or something more complex).

It’s also vital to recognize that with so many octave divisions, it’s workable to swiftly shift from a conventional key to a distant one, which was done and debated among composers at the time (like Gesualdo).

Conclusion

D♯ and E♭ are the same notes in modern, equal temperament tuning and sound the same.

It does, however, matter in which context you are using the notes as we’ve illustrated a B major scale written with flats instead of the sharps may sound the same but is challenging to read on paper.

In the Renaissance and early Baroque periods, D♯ and E♭ were different notes, as illustrated by the arciorgano and arcicembalo.

Select Resources for Further Reading