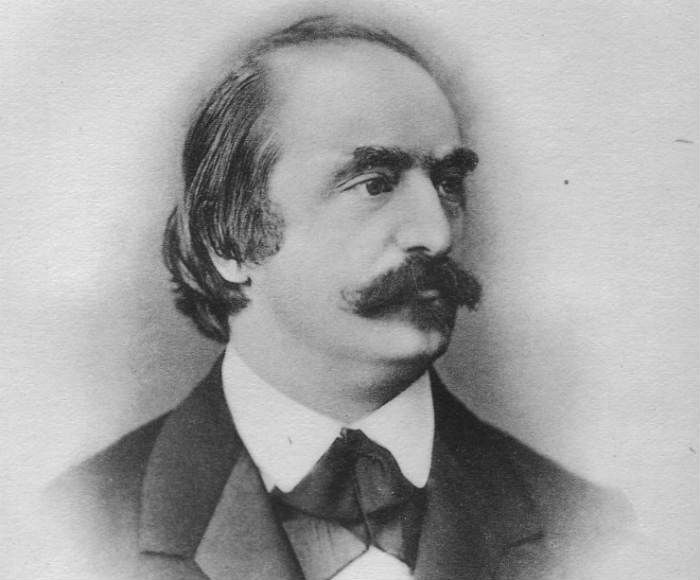

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, Eduard Hanslick enjoyed a position of great power and influence as one of the most widely read critics in Vienna (first at Die Presse, then with Die Neue Freie Presse). Nowadays, he is known mainly through biographies of Wagner as a narrow-minded twit unable to appreciate the genius of the “Music of the Future.”

Born in Prague in 1825, Hanslick studied law but his love of music led him to a teaching position at the University of Vienna which culminated in a professorship in 1870. His most famous work, 1954’s The Beautiful in Music, is one of the few instances of his writing being translated into English.

Hanslick was the most vocal opponent to the revolutionary musicians of his time. Wagner already had a devoted following and Hanslick feared the direction of his leadership. He attacked disciples of Wagner with particular ferocity. In one review of Anton Bruckner, he wrote, “It is not out of the question that the future belongs to this muddled hangover style – which is no reason to regard the future with envy.”

It should be mentioned that Hanslick was not merely a commentator in this fight. He endured his share of blows as well. Indeed, Wagner himself famously humiliated Hanslick by inviting him to a preview of Die Meistersinger where the pedantic character later known as Beckmesser was named “Hanslich.”

A staunch proponent of Brahms and other conservative musicians, Hanslick often swung his criticism to extremes in support of his ideology. These extremes left him vulnerable to a harsh reckoning by modern scholarship. Some have attempted to examine Hanslick’s legacy in a more sympathetic context, as with In Defense of Hanslick and Rethinking Hanslick. Overall, however, the consensus appears to be that he simply went too far too many times.

For any musician who has ever endured a poor review, take comfort in the company you keep thanks to Hanslick. Here is a sampling of his thoughts:

On Liszt’s Les Préludes

One finds no theme that could be called original or profound, quite the contrary, there are signs of banality in both its pathos and its sentiment.

On Verdi’s Otello

The master set himself a noble objective but much of the worth has been sacrificed in its attainment: naiveté and youth. And youth in music is melody. In his earlier operas the young Verdi did not always know quite what to do with his melodies – but he had them.

On Richard Strauss’ Don Juan

This is no “tone painting” but rather a tumult of brilliant daubs, a faltering tonal orgy, half bacchanale, half witches’ sabbath.

On Tchaikovsky in general

What lamentably trivial Cossack cheer we had to suffer in the Finale of his Serenade, opus 48, in his Violin Concerto, in his D major Quartet, or in the 3rd movement of his Suite, opus 54.

On Bruckner’s 8th Symphony

I found this newest one, as I have found the other Bruckner symphonies, interesting in detail but strange as a whole and even repugnant.

On Wagner’s Götterdämmerung

One can listen to this incoherent ardour amidst the fluctuations of deafening and nerve-racking orchestral effects for only a short time without relaxation.

On the second act of Wagner’s Die Walküre

[A]n abyss of boredom.

On Wagner’s Prelude to Tristan und Isolde

[It] reminds me of the old Italian painting of a martyr whose intestines are being slowly unwound.