There are less than 700 remaining Stradivari violins and, on August 6th, one of them was rightfully returned to the family of its rightful owner after it had been missing for 35 years.

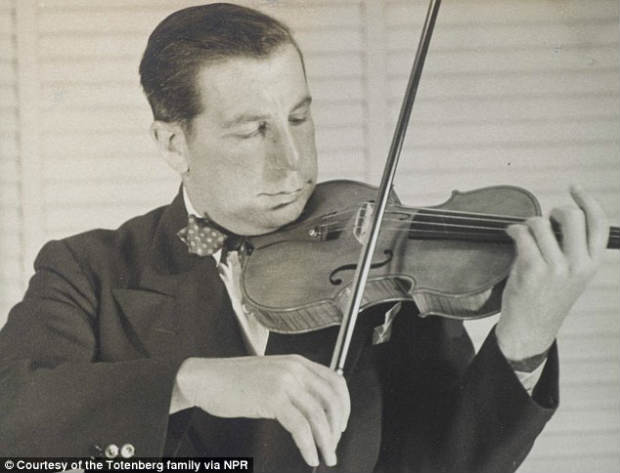

Known as the Ames Stradivarius because it was played by virtuoso George Ames during the nineteenth century, the violin was made in 1734 by Antonio Stradivari; it belonged to violin virtuoso Roman Totenberg, who had worked with Igor Stravinsky and had performed as a soloist with major orchestras. He had acquired it for $15,000 in 1943– in case you thought he struck a great bargain, just bear in mind that those $15,000 roughly correspond to $200,000.

It was stolen in May 1980 from Totenberg’s office at the Longy School of music in Cambridge, Massachussetts, and, at the time it was stolen, it was valued $250,000– these days, those violins sell for millions.

The violin resurfaced on June 26, 2015, when a California woman named Thanh Tran brought it to New York, in order to have it appraised by violin maker and dealer Philipp Injean, who recounted his examination on The Strad.

Ms. Tran claimed her ex husband had given her a locked case before his death in 2011, so she had no idea what it contained until she and a boyfriend broke it open with a screwdriver. “The violin looked magical but sad, with all of its strings busted,” she said in an interview with the Associated Press.

The man who left the violin to Ms. Tran was Philip S. Jonson, an “aspiring violinist” (per Roman’s daughter Nina Totenberg’s words) who was seen loitering around the place where it was taken. He attended Longy School of music from 1976 to 1979, and Roman Totenberg was on faculty during that period.

After the incident, an ex-girlfriend of his had told Nina she was sure he had taken it. At a recent news conference, Nina Totenberg recalled that, given that the Totenberg family could not ask for a search warrant, her mother would ask her friend if she knew some mobster who could break into Johnson’s apartment and search for the violin.

Now that the violin has been returned to where it belonged, the Totenberg family is planning to have it restored: they hope it will land in the hands of a great artist, and not a collector. It would be best, from now on, to refer to it as the Ames-Totenberg Stradivarius.

While reminiscing about his stolen violin during an interview with CBS in 1981, Totenberg recalled that it had taken him a considerable amount of time to use the violin at its full potential. “It took some time to wake it up,” he said, “to work it out, find all the things that it needed, the right kind of strings and so on and so on.”

The tonal qualities of the Stradivari are well renowned: however, The Washington Post reports, some scholarship maintains that Mr. Stradivari’s creation owe much to their unique sound to the distinctive time the wood they are made of —spruce for the top of the violin, maple for the back— grew.

Those trees, in fact, grew in the forest of North Europe during the so-called Little Ice Age, which brought colder seasons for quite a lengthy period of time. This resulted in a more uniform character and a higher density, which, allegedly, was an important factor in determining the tonal qualities of the instruments.

What’s more, from 1645 to 1715, the sun displayed an unusual behavior, which is known as the Maunder Minimum after the two scientists, Annie and E. Walter Maunder, who discovered it. During that time, the magnetic fields were very weak and, as a consequence, there were barely any sunspots to be seen on the sun.

Since we are on the brink of another solar minimum (the sunspot cycle 24 is nearing its end), can we expect a new fresh batch of Stradivari in the near future?