While philosophers and scholars of the pre-modern era kept studying music from a harmonic point of view and often delved deeper into the concept “musica universalis”–this time was mediating it with Christianity, starting from the eighteenth-century discussions surrounding the art of music became more articulate and varied.

Pythagoras (c.570 BC-c.495 BC)

Pythagoras was credited with having elaborated on the theory of the musica universalis, where the numeric proportions observed in celestial bodies translated into musical pitches and hums based on their orbital spheres.

“There is geometry in the humming of the strings, there is music in the spacing of the spheres.” (Pythagoras)

Plato (c.428 BC-c.348 BC)

Plato maintained that the arts could shape one’s character to a great extent, and, for that reason, they needed to be strictly controlled. Poetry, drama, music, painting, dance can all stir up emotions.

Along with poetry and drama, music was regarded as important for young people’s education in his ideal republic— only the “good” music, that is.

He was largely influenced by the theories of Pythagoras and his numeric mysticism, inspired by a series of overtones connected to the vibration of a string. “Ordered” music (i.e., the one following harmonies) meant ordered souls.

“Music is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination, and charm and gaiety to life and to everything.” (Plato)

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)

Leibniz had a Scholastic background, and, as a consequence, music was regarded as a byproduct of mathematics: he defined it as “an unconscious exercise in arithmetic in which the mind does not know its counting.”

However, he broadened his scope when he reflected on what made a successful composer, namely practice, vivid imagination, and the knowledge of the tradition, just like a poet needs to have read good poets prior to venturing into writing verse.

Feelings of pleasure and pain were brought by consonance and dissonance.

“Music is the hidden arithmetical exercise of a mind unconscious that it is calculating.” (Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz)

William Hogarth (1697-1764)

In his Analysis of Beauty, Hogarth isolated six principles that could affect beauty: fitness, variety, regularity (in the sense of “composed variety”), simplicity, intricacy, namely a difficulty in understanding that, however, challenges the individual in a pleasurable way, and quantity.

He concluded his treatise with an analysis of the Minuet since he considered Dance to be beautiful. Music, to him, remained ancillary and subordinate to dance.

“The minuet is allowed by the dancing-masters themselves to be the perfection of all dancing.” (William Hogarth)

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

In his Critique of Judgement, Immanuel Kant discussed music while elaborating his judgment on beauty, which you can read here (it’s not the most comfortable read).

Among the forms of art, he ranked instrumental music the lowest because, unlike other arts, it had no moral purpose, nor did it engage the intellect to a satisfactory degree.

Adding words, as in song or opera, can somehow nobilitate that form of art.

“Even the song of birds, which we can bring under no musical rule, seems to have more freedom, and therefore more for taste, than a song of a human being which is produced in accordance with all the rules of music; for we very much sooner weary of the latter, if it is repeated often and at length.” (Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment)

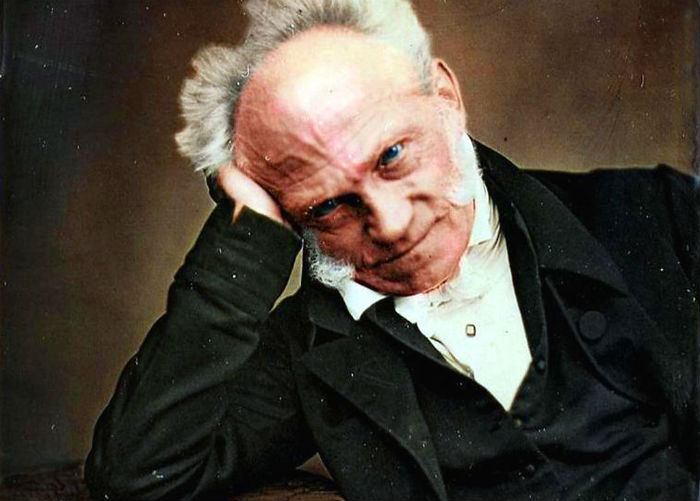

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

Happy-go-lucky Schopenhauer theorized that aesthetic experience could elevate the subject from the will’s domination (don’t forget that, to him, humankind is a slave to incessant cravings) raising him to a level of pure perception. He saw music as a direct manifestation of will—able to represent the metaphysical representation of reality—.

In contrast, arts like literature and sculpture were too entangled and related to human forms and emotions to measure up to music. Even in the opera, the libretto was subordinate to the score itself, being a “linguistic representation of a transient phenomenon.”

His philosophy of music deeply influenced Wagner’s work, to the point that, even in his written works of music theory, he eventually became aligned with Schopenhauer. We have to thank him for the rise of the Symbolist movements and the development of the concept of Art for Art’s sake.

“The inexpressible depth of music, so easy to understand and yet so inexplicable, is due to the fact that it reproduces all the emotions of our innermost being, but entirely without reality and remote from its pain… Music expresses only the quintessence of life and its events, never these themselves.” (Arthur Schopenhauer)

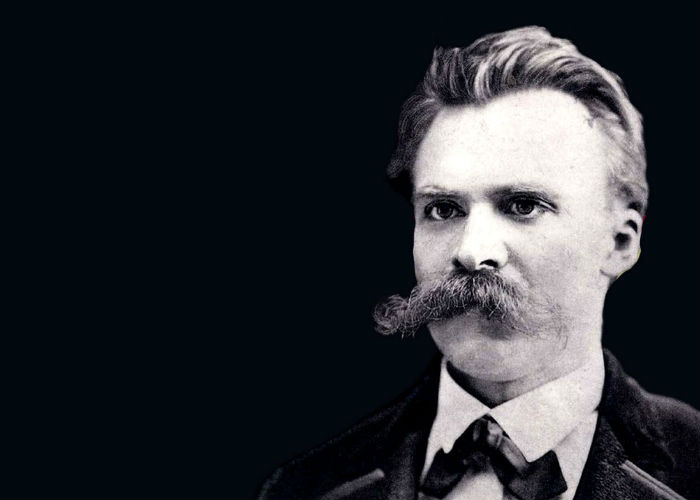

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

Don’t let his feeble attempts at composing fool you: Nietzsche devoted a good part of his philosophy to the meaning of music. The late romantic concept of Art for art’s sake was an Idea he completely rejected, as, for him, music served a purpose. That art, however, was not intended for the audiences, but rather for a new kind of artist.

What’s more, to Nietzsche music was the last breath–the swan song, actually–of a particular cultural era: Händel captured the spirit of Lutheranism and the reformation, Mozart the age of Louis XIV; Beethoven and Rossini the spirit of the 18th century, and Wagner–whom he first worshipped, then scorned– the last representative of the dying German culture.

“Without music, life would be a mistake.” (Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, Or, How to Philosophize With the Hammer)

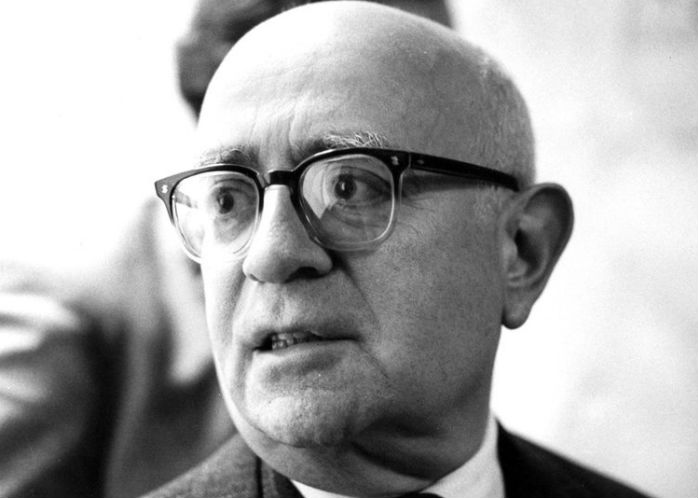

Theodor Adorno (1903-1969)

Music critic Alex Ross defined Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno, the reigning godfather of German musical thought and the dark prince of intellectual life.

He studied with Alban Berg, Schoenberg’s pupil and, from him, he absorbed the notion that music had to strike to unknown regions in order to stay true to a Wagnerian ideology of progress: hence, music has to get rid of all sounds that ring familiar and are true to the notion of “beautiful”.

When, upon Hitler’s ascent, he migrated to New York, he made scathing generalization regarding how people expressed music appreciation.

To him, who embraced post-Marxism, any work that attracted large numbers of people had no value, and he openly despised Toscanini and his sold-out concerts, claiming that the fans were too “retarded” to truly appreciate the music of the great Masters: instead, they worshipped the money they were spending for that experience.

“They [the critics] deal with Schoenberg’s early works and all their wealth by classifying them, with the music-historical cliché, as late romantic post-Wagnerian. One might just as well dispose of Beethoven as a late-classicist post-Haydnerian.” (Theodor W. Adorno, Essays on Music)