Acclaimed cellist Julian Lloyd Webber delivered a great message to music students at the Birmingham Conservatoire. We reprint his speech in its entirety:

In 1977 I won a bet with my brother Andrew. This meant that he finally had to write me the cello piece he had been promising for years. The trouble was that he decided it should be a piece for cello and rock band – and the classical music world was a lot stuffier then than it is now. That was the time when melody, rhythm, and harmony were taboo in contemporary classical music and I was warned by friends and colleagues alike that I would literally ruin my career by recording it. But I believed in the piece so I took the chance.

And it didn’t ruin my career. Variations (aka the South Bank Show theme) was unexpectedly successful. Perhaps because audiences were actually crying out for melody, rhythm, and harmony. Perhaps because we had shown that pushing at boundaries need not be a bad thing. But more likely it was because I never left my classical roots behind because – much as I liked to experiment – I knew that my bedrock as a solo cellist would always be based on that five-hundred-year treasure trove called classical music.

Since I recorded Variations everything has changed – yet nothing has changed. Forty years ago I was told that it had never been harder to make it in the music business. Today’s young musicians are told exactly the same thing and especially they are told that it has never been harder to make it as a classical musician.

But this isn’t true – it is so much easier to make it today! Forty years ago there were none of the amazing opportunities that digital technology affords young musicians. And it is so much easier to experiment and push at boundaries because they have already been broken down. Now everything is about creativity and imagination – it’s about classical musicians working cross-genre with spoken word or dance. It’s about classical composers working with digital games. It’s about the Pet Shop Boys at the Proms. It’s about Laura Mvula writing songs on her laptop during her lunch break, forwarding them to people in the business, getting signed by RCA and having her own late-night Prom. It’s about the viral YouTube clip by 2Cellos playing AC/DC’s Thunderstruck: Vivaldi metamorphoses into AC/DC in front of a suitably shocked and bewigged 18th-century audience and – most importantly – it’s had over 24m views. Now, these two young Croatian guys are touring vast American arenas as the support act for Elton John and have landed a recording contract with Sony.

So am I talking about ‘selling out’, demeaning yourself to make a career? No, I am not. First of all the 2Cellos can really play – which is always a prerequisite for success as an instrumentalist. Second – in today’s more enlightened world – they could easily return to their classical roots and be successful if they want to – whilst at the same time bringing a huge established fan base with them.

Any aspiring soloist would be wise to remember that the word solo means ‘on your own’. My own lonely path began when I was 13 and made up my mind to become a solo cellist. At school, my classmates were busy collecting cigarette cards but I was more interested in collecting obscure cello concertos off the radio. I became obsessed with the cello repertoire and I would tape anything with a solo cello in it. By the time I was a student at the Royal College I was spending days at a place called the British Institute of Recorded Sound. It was run by an eccentric gentleman named Patrick Saul, who realised that historic broadcasts were disappearing into the ether and he set about recording anything and everything. By the late 60s – when I’d found out about it – he had amassed an astonishing collection of hundreds of thousands of 78’s, LP’s and reel to reel tapes (apparently his favourite recording out of all of them was the “mating call of the haddock”)! He also maintained a slightly haphazard card index which conveniently listed recordings under composers, cellists – or even just plain ‘cello’ – and I would consult this on a regular basis to seek out ever more obscure music for my instrument. The trouble was that Mr. Saul didn’t seem to know where any of the recordings actually were and I would spend long hours becoming over-familiar with his backside while he crawled around the floor trying to locate the cello concerto I’d requested by the likes of Vladimir Dukelsky or Lubomir Pipkov.

That is how difficult and time-consuming everything was back then! Now, wherever you are in the world – all that music and all those recordings I would spend weeks researching are available at the click of a mouse.

And everything cost so much more! If you needed to do a mail-out to concert promoters you had to produce your own brochure, you had to type three or four hundred envelopes and you had to lick three or four hundred expensive stamps.

Yet in inverse proportion to today’s ease of discovery, I keep coming across a lack of curiosity, a lack of adventure and a lack of desire to shake up the status quo.

Young cellists come to play to me and ask for my advice on how to become a soloist. Yet they always come with the same pieces! – the Bach Suites, the Brahms Sonatas, the Elgar or Dvorak Concertos. They need to get real. Because it is massively unlikely they will make a career by playing these pieces – at least at the beginning. How I long for a cellist to come and surprise me with a piece of music I don’t know! Instead, I’m receiving a sense of entitlement that is saying “I can play these great masterpieces, therefore, I am entitled to have a great career”. But it has never been like that and it has never been less like that now!

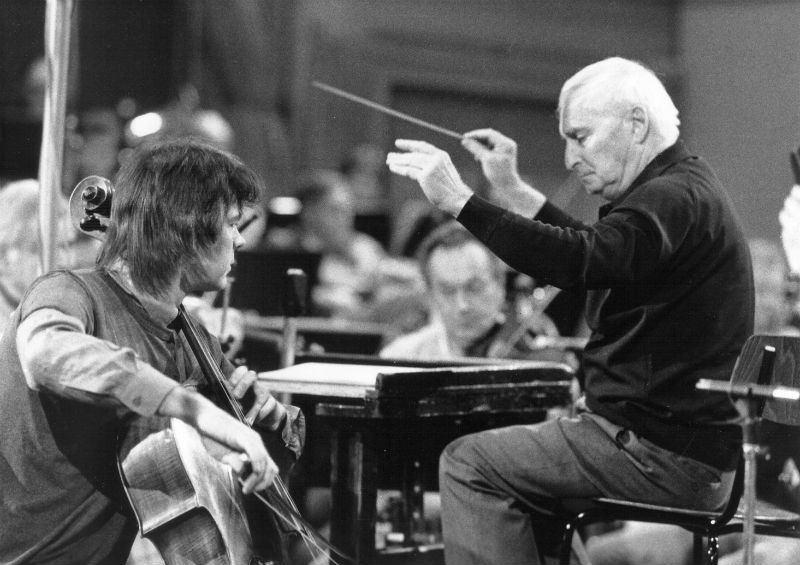

My two cello ‘idols’, Pablo Casals and Mstislav Rostropovich, both established their careers by pushing at boundaries – Casals by revealing and insisting that Bach’s Cello Suites were not exercises but were, in fact, great masterpieces, Rostropovich by inspiring and bullying all the much older composers around him – Prokoviev, Shostakovich and Khatchaturian – to compose new music for the cello which he would then play and tour abroad – which, of course, enabled him to ‘spread his wings’ outside the stiflingly restrictive Soviet Union.

To succeed in today’s music business the aspiring musician needs to give almost as much time and thought to business-related matters as they give to practising their art. They need to find their unique space in the market place. They need to find out what they have to offer that is different from everybody else. They need to answer the question ‘Why should anyone be interested in you?’ In other words – as well as being necessarily brilliant at what they do – they will need to think laterally.

In China 20m children are studying the piano, dreaming (along with their parents!) that they will be the next Lang Lang, Yundi Li or Yuja Wang. Of course, they can’t all be soloists but one or two of them just might. And I guarantee they will come from the very few who have been thinking laterally. So it would be a lot more productive for them to spend that final hour out of their six or seven hours of daily practice (and that’s how many they will need to be doing) planning their route to success! Because there’s no point in shutting themselves away becoming the greatest pianist, violinist or cellist on the planet if no one ever discovers this wondrous piece of information.

And in case they might think that competitions are a short cut to success – I don’t! With very few exceptions – and the BBC Young Musician of the Year is one – they are microcosms of corruption far more dependent on who studied with who or which teachers are on the jury rather than who is the finest musician.

And string players shouldn’t get too strung up about their instruments – I was in my 30’s before I had a half-decent cello. The player is at least 90% of the equation – remember the story of the blue-rinsed lady who gushed to the great violinist Jascha Heifetz that his Stradivarius had “sounded wonderful”? Putting the instrument to his ear Heifetz replied: “That’s strange, I can’t seem to hear a thing.”

The only lasting way to success in the music business is to discover your own voice in a massively over-crowded marketplace.

Both Casals and Rostropovich understood that it wasn’t enough to play the same old pieces brilliantly. They needed to be creative and imaginative too.

But that doesn’t mean forcing musicians in directions they don’t want to go in or playing the music they don’t believe in. If they try to do that then they won’t have the passion they will need to succeed. Casals passionately believed in the Bach Suites and Rostropovich passionately believed in expanding the cello repertoire – but he also realised that for every good piece he received he was going to have to learn and play at least ten bad ones as well.

So once a musician discovers their passion it will all come down to hard graft – hard graft that continues for years because it’s as easy for careers to go downhill as it’s hard to build them in the first place. They will need to keep finding new ways of engaging their audiences, of selling records and of filling venues – otherwise, new kids on the block will soon be taking their place.

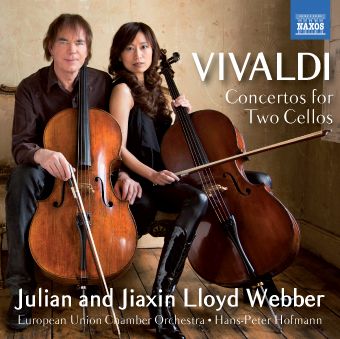

Shortly before injury forced me to stop playing I had made a recording called A Tale of Two Cellos with my wife and fellow-cellist, Jiaxin. It had been a labour of love (in every sense of course). We’d spent many months researching the repertoire, arranging it for two cellos and preparing it for our recording – so I was determined to promote it. When the offer came to appear on BBCTV’s Breakfast Time I persuaded my wife and our pianist that we had to make the unpaid trip to Salford. If only life was so simple! Guests need to travel up the night before, stay onsite and be up at 4.30 next morning ready for their 5 am sound-check. Our train was cancelled because of storms and flooding but somehow we managed to get on the one train that did leave for Manchester that evening. It was an overcrowded nightmare of a journey and we stood all the way with the cellos. As we finally pulled into Manchester at around 10.30pm I got a phone call from Breakfast Time. Nelson Mandela had died so our slot had been ‘pulled’.

A few days later, in the middle of our rehearsal for that night’s concert at London’s Cadogan Hall, I got another call from Breakfast Time:

“We’ve had a cancellation for the day after tomorrow – can you do it?”

“Yes” I replied unhesitatingly.

“No way” said Jiaxin when I told her the news.

Suffice to say that at 4 pm next afternoon we were heading to Salford all over again. Following our appearance on Breakfast Time, A Tale of Two Cellos was the Number One Classical Album over Christmas. And as a result of the lengthy 25–date UK tour we made earlier this year which – alongside London, Birmingham, Edinburgh and Manchester took in the Pavilion Rhyl, the Pier at Cromer and the Marina, Lowestoft, A Tale of Two Cellos has become one of the best-selling Naxos CDs of all time.

I share this to explain why – even if they are sixty-two and have a career-threatening injury – a musician needs to keep hold of both the passion for what they do and their hard graft.

So what would I be doing if I was starting out as a performer now? I’d be all over YouTube and Spotify like a rash – listening to masses of different music in the comfort of my own home or a café or a pub instead of watching Patrick Saul’s backside at the British Institute of Recorded Sound. I’d be booking the recording studios at my music college, experimenting with different microphones, getting the best sound I possibly could and uploading the results to YouTube and anywhere else I could find.

I’d be going on Social Media forums, posting links and asking for feedback. And all of this would be costing me nothing.

None of this is about self-aggrandisement – it’s about communicating and sharing your passion in the things you love and believe in with others. I would be doing it now if I could and I will be doing it again in my next music-related role.

Years ago I wrote a book called Travels With My Cello. Its last paragraph went like this:

The life of a solo musician is tough and exhausting, both physically and mentally, but I would definitely make the same choice again. For in the end, there is something which sustains you through all the difficulties, something far stronger than ambition, wealth or fame. Let that great cellist, Pablo Casals, say it for me. After a particularly moving performance he was asked:

“Mr Casals, can you tell me, are we in heaven or still on earth?”

Softly he replied: “On an earth that is… harmonised.”

As so often, Casals was right. And my advice to any young musician who does find their way to make it in the music business: catch it while you can, make the most of it and enjoy every second of it because – sad as it may be – nothing lasts forever.