There is all manner of odd conventions, rules and practices that have accumulated over music’s lengthy history.

To the non-musician, they may seem outdated, irrational, or even incomprehensible, but they are at the heart of music-making and often in the armoury of every practising musician.

Some of the stranger aspects of music include things that are broadly called ornaments. Under this heading come a bewildering array of options that are regularly seen in notated music and heard in performances every day.

They have attracted the category of ornaments as although they are an important part of any piece of music, they could be removed without an overly drastic alteration to the sense and continuity of the piece.

They ornament the work, enhancing it and colouring it, but in this way are only considered to be extra to the existing material. In some music, this can be different, but for this article, we will content ourselves with this premise.

Let’s look in more depth at what an ornament is. One of the longest surviving ornaments is the trill. This involves the rapid alternation of a note to an upper note usually a semitone or a tone away.

Frequently the trill appears at the end of a phrase to conclude it with a flourish. In some earlier eras of music, the trill could be viewed as a demonstration of a player’s virtuosity.

Another well-respected ornament is the mordent. These are like an extremely abridged trill. There are upper and lower mordents which as the name suggests means a quick move from the starting note either up a tone or semitone or down the same interval.

Perhaps the most recognised mordent is at the start of that most ominous of works, the Toccata and Fugue in D minor by JS Bach (BWV 565).

So where do the acciaccatura and the appoggiatura fit into this picture? Both of these delicate musical extras are often referred to as grace notes.

Quite where the term originated I am not certain but what they do is to add a level of expressivity to a melodic line (usually), as well as impacting on the underlying harmony. There are a few other subtle differences too that we can explore further.

Acciaccatura vs Appoggiatura

The illustration above is of an acciaccatura. You’ll notice that there are two notes in the illustration, one small one followed by a normal-sized note. The small note is the acciaccatura.

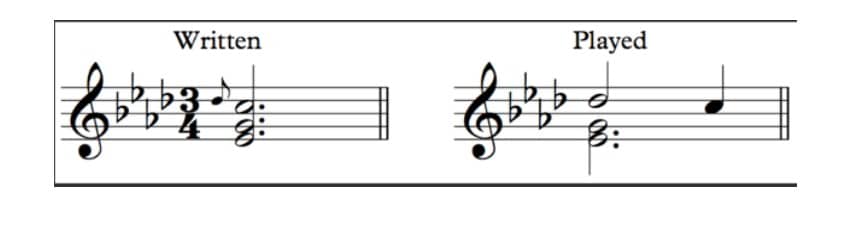

What you may also have spotted is that the smaller note has a line through its tail as if it has been crossed out. This indicates that the acciaccatura holds no time value in the bar.

To clarify, the crotchet that follows has a value of one beat (if we’re counting in simple time ie: 2/4, 3/4. 4/4…) The acciaccatura does not add extra time to the bar in which it appears but is crushed up to the full value note and is played on the beat.

It is used to great effect in numerous pieces of music and even though considered to be an ornament does bring character and expression to a melody. That character comes in the form of a passing dissonance that is often resolved when the melody returns to the main note.

There are some brilliant examples of music that use the acciaccatura to great effect. One of my favourites, amongst many, is ‘The Hut on Fowls Legs’, from Pictures at an Exhibition by Modest Mussorgsky. ‘Extensions’ of the acciaccatura exist too.

Perhaps more commonly discovered in contemporary music, they are sometimes pairs of acciaccatura or larger groups that are to be played either extremely rapidly or with a greater degree of flexibility in the way we see in Chopin or Liszt.

The example above illustrates the appoggiatura. Perhaps the first thing you will notice is the fact that this little note is not crossed out in the manner in which the acciaccatura was.

This simply is because the appoggiatura requires a different approach when performing it. Unlike its cousin, the appoggiatura isn’t a note to be succinctly played but one that is a minor thief.

What the appoggiatura does is steal time from the note that it stands next to. From the example, you can see that the appoggiatura ‘D’ has taken two beats from the three beat ‘C’.

In a similar way to the acciaccatura, the appoggiatura alters the harmony at the same time as subtlety modifying the melody.

Here, the chord of C minor is momentarily but significantly transformed into a dissonant chord of C minor with an added 9th (ie: the ‘D’).

Even though the composer could easily have elected to close the phrase on a C minor, they deliberately chose to suspend the closure with an appoggiatura. This delay in harmonic resolution provides an interesting additional colour, even tension, to this part of the piece.

You could argue or ask why the composer didn’t just notate the music that way in the first place rather than using an ornament. Well, the answer is not completely straightforward.

One response is that an ornament is decorative, not essential yet as we have discovered, taking it out of the music leaves an unsatisfactory gap. We notice something missing.

The other, more comprehensive response should include a reference to musical conventions, particularly those that surround Baroque music. These are complicated and often relate to a particular country like Italy, Germany, France or England.

Each of these countries had conventions and stylistic expectations that governed how performers would play the appoggiatura as well as other ornaments.

It was often felt in the Baroque period that a performer’s technical armoury must include an active knowledge of appropriate ornamentation.

What this means is that composers did not always notate these ornaments but expected performers to know where and how they would want them included.

Over time, composers took a firmer hold on this practice and so the detailed notation of appoggiaturas and acciaccaturas, alongside numerous other ornaments became the custom.