We all know that music is beneficial to the human mind: it lowers anxiety, pain levels, it alters your brainwaves and, of course, helps infants’ brain development.

The virtues of music have been known since the dawn of time: ancient mythology, regardless of its geographic location, is rife with myths referencing the power of musical instruments, which are usually able to bring order to chaos, charm deities and, actually, solve conflict within the same kin.

Bragi, the Golden Harp and the Song of Life

Odin’s son Bragi, whom he sired with the Giantess Gunnlod, the daughter of the guardian of the vats of mead, was presented with a golden harp by dwarves as soon as he was born. They then set him on one of their vessels and sent him out to the world.

He reached the realm of Nain, the dwarf of death. Bragi had barely shown signs of life, but then he suddenly sat up, seized the golden harp and started singing the song of life. While he played, his vessel kept moving, and soon it was cast ashore.

Bragi set foot on the land, and, as he threaded his way into the forest, he kept playing: the sound of his music made the trees bud and bloom, while the grass was quickly strewn with flowers.

There, he met Idunn, the goddess of immortal youth. Together, they set to Asgard, where Odin traced runes on Bragi’s tongue and made him the official “bard” and composer of songs honoring the gods and the heroes that the Valkyries brought to Valhalla.

Dagda and Uaithne, the harp that could put the seasons in order

Uaithne is the harp that belongs to the Dagda, a “fatherly” God who also acts in the capacity of protector of the tribe. His harp, which can both put the seasons in the correct order and command order in battle, is also known as Dur da Blá, “The Oak of two blossoms” and “Coir Cethar Chuin,” the Four Angled Music.

After the second battle of Mag Tuired, the Fomorians had seized Uaithne, and the Dagda found it in a feasting house. He had bound the harp so it would not sound until he would call to it. So, he called to it and the Uaithne immediately sprang from the wall, and, while on its way to its master, it killed nine men.

Pan and his flute

Pan’s flute was fashioned from hollow reeds. Syrinx was a water nymph of Arcadia, the daughter of the river-god Landon. She was returning from the hunt one day as Pan met her. She wanted to escape the god’s seduction so, she ran away and eventually joined her sisters, who immediately changed her into a reed.

The air blowing through such reeds produced a plaintive melody, and Pan, who was still infatuated and unable to tell one reed from the others, took some reeds, cust seven pieces and joined together in decreasing lengths, thus forming the musical instrument “syrinx” that eventually bore the same name of his beloved Syrinx.

Hermes and the tortoise-made lyre

Ever since he was an infant, the God Hermes, son of Zeus and Maia (the most beautiful of the pleiades) was cunning and well-versed in the “art” of theft.

A few hours after his birth, he tried to steal some of the oxen belonging to his brother Apollo but, on his way, he found a tortoise. He killed it and, by stretching seven strings across its shell, he invented the lyre, and immediately started playing with remarkable skill.

After amusing himself with the instrument for a while, he returned the object to his cradle and eventually succeeded in separating fifty oxen from Apollo’s herd. A dispute arose between the two brothers, and, at the end of the conflict, they were in Hermes’s chamber, and Hermes touched the chords of his lyre.

Up until then, Apollo had been accustomed to the sound of his three-stringed lyre and the syrinx (a wind instrument) and, as soon as he heard the sound of the instrument crafted by his brother, he told Hermes he could keep the oxen and get dominion over flocks and herds in exchange for the tortoise-made lyre.

Orpheus, his lyre and his singing severed head

Orpheus’s wife Eurydice was walking among her people in tall grass at her wedding when a satyr laid his eyes upon her. In an affort to escape him, Eurydice fell into a nest of vipers and was fatally bitten on her heel.

Soon after, Orpheus discovered her body and, overcome with grief, he started playing his lyre. He played such a sad, mournful and beautiful song that all the nymphs and gods wept.

They suggested Orpheus travel to the underworld in order and, eventually, his music softened the hearts of Hades and Persephone, who agreed to let Eurydice return among the living on one condition: Orpheus had to walk in front of her, and avoid looking back until they both reached the upper world.

As soon as he re-emerged, Orpheus turned back to look at her, but, unfortunately, Eurydice was still in the underworld and Hades and Persephone demanded that both be in the upper world in order for Orpheus to look at his wife. Orpheus’s anxiety caused Eurydice to vanish forever.

As far as his death is concerned, Ovid recounts that, after his mishap with Eurydice, he abstained from having female lovers and transferred his affections to young boys, eager to enjoy their “early flowering.”

Many women grieved at this rejection, particularly the Ciconian women, who were followers of Dionysus. They first threw rocks and sticks at him while he was playing his lyre but the melody was so beautiful that rock and sticks refused to touch his body.

So, in a Bacchic frenzy, the women tore him to pieces. His head and his lyre were still capable of singing songs and floated down the Hebrus river to the Mediterranean shore. The waves then carried them to Lesbos, and the inhabitants eventually buried his head. As far as his lyre is concerned, it was subject to a katasterismos: the Muses carried it to heaven and placed it among the stars.

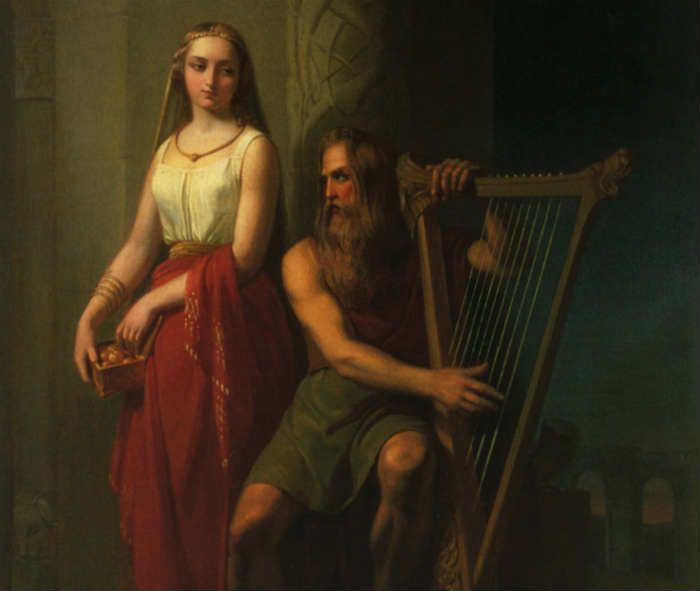

Väinämöinen and his two harps

Finnish demigod Väinämöinen went to a waterfall. There, he killed a pike and fashioned a harp out of the bones of the fish. However, he dropped his instrument into the sea, and thus it fell into the power of the sea gods, hence the origin of the music of the ocean on the beach.

So, the hero made another one out of the forest wood, and with it, he descended into Pohjola, the underworld, looking for the mystic Sampo, an indeterminate artifact that could bring fortune to its beholder.

In that realm of darkness, Väinämöinen struck his harp and sent the inhabitants to sleep: so he ran off with the Sampo and he had almost reached the land of light again when the inhabitants of Pohjola woke up again, and went after him to retrieve the Sampo which, in the struggle, fell into the sea and was inevitably lost.

Tristan and the harp that set the lovers’ tragedy in motion

Well, technically, the two famous star-crossed lovers both drank a love potion disguised as poison, but before their affair officially started, they got to know each other thanks to Tristan’s harp. Irish duke Morholt— a giant and very powerful knight— demanded tributes from Cornish King Mark.

Tristan, who was a distinguished knight in Cornwall, decided to face Morholt in single combat, and three days later the two knights met on an Island: Tristan had destroyed his own boat so that only the winner could leave the island alive and, after a fierce battle, Morhold was mortally wounded, while Tristan’s wound was apparently less serious, even though Morhold had wounded him with a weapon smeared with poison. Only Isolde the Elder, Morhold’s sister, could heal that wound.

Upon the Morhold’s burial, Isolde the Elder’s daughter Isolde the Fair found a splinter of Tristan’s sword in Morhold’s wound and kept it with her. Soon after Tristan’s return to Cornwall, his wound began to fester and so, since no physicians could heal him, he tried to go back to Ireland to get either of the Isoldes to heal him, even though he had murdered one of their relatives.

He disguised himself as Tantris, a harpist. His skill with the harp was so remarkable that Isolde the Fair wanted to learn how to play, and, depending on what version you are reading, either she or Isolde the Elder healed his wound and, forty days later, he went back to Cornwall.