If you have ever seen Baroque architecture and paintings you will have a good idea of how ornate its appearance is. The style emanated from late 16th Century Italy and was characterized by grandeur, gilded statues, bright colors in the artwork, filled with opulence and sensuality. I mention this as it is paralleled in the music of the period. Baroque music is deeply sensuous, rich with ornamentation, and complex textures just as the buildings in which it was performed.

The ornaments that decorated the music of the Baroque reflected the style of the period and included an extensive list of options for the composer and performer. Conventions were established amongst musicians and composers as to which ornaments should be played and when alongside, how they should be executed during a performance. This, to a large extent, depended on whether you were following the Italian or the French set of conventions; both of which could differ significantly. France and Italy dominated the Baroque Period of music which is why they cultivated the rules that governed musical conventions. In broad terms, the French convention was more classically streamlined whereas the Italian unashamedly elaborate.

Baroque Trills

Amongst the dazzling array of Baroque ornaments available the ‘trill’ was one of the most commonly used. It is also one of the few that has survived into current musical use even though its ‘meaning’ is now quite different. To try to explain what a trill is quite a challenge, but I will attempt a definition. Essentially, a trill marking in a piece of music indicates to the performer that a rapid alternation of the written note to upper note is required; either at the interval of a tone or semitone. This is how a trill would be read and performed today unless the composer expressly indicated otherwise.

This is how a trill is notated today. The wavy line is not always part of the notation but helps to indicate quickly what the performer needs to do.

This is where our story begins to become a little more involved. The question that arises from this notation and a small amount of knowledge about Italian and French Baroque conventions, on which note does the trill begin? Many notable practitioners would claim that it is a matter of taste, but others who would adopt a stricter approach. The argument follows that the trill is not only ornamental but also a harmonic device. This means that the note on which the trill begins needs to consider the dissonance it creates with the underlying harmony. One key aspect of this is whether or not the trill creates a parallel 5th with the additional parts which would not be acceptable, or if it creates a ‘suspension’ that is then resolved at the end of the trill.

To resolve potential conflicts and confusions, many French composers included a ‘chart’ of their ornaments at the start of their compositions that began with the Chambonnieres printing of 1670. Jacques Champion de Chambonnieres (1602-1672), was a formidable harpsichordist and composer who was felt to be one of the finest musicians of his time. Many of his compositions have survived and are worthy of greater exposure.

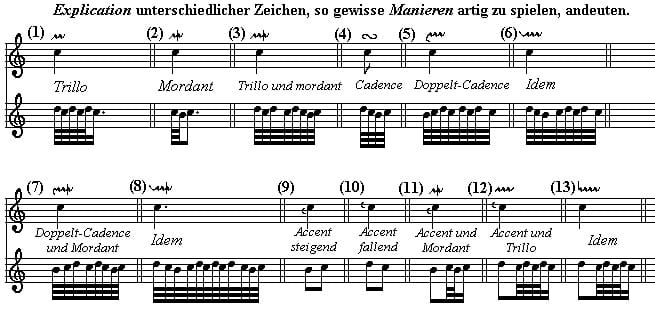

This may all sound to us in the 21st Century as somewhat unnecessary, but this practice was not limited to Chambonnieres. JS Bach (1685-1750), made a table of ornaments reportedly for his son WF Bach that has been of immense value to performers wishing to play Baroque pieces in the manner in which they were intended. Bach highlighted the existence of four different types of trill. These were as follows: a normal trill; an ascending trill; a descending trill and a half or short trill. From this brief list, it becomes possible to understand the complexities that surrounded Baroque performance conventions.

In all probability, this was firmly in the mind of CPE Bach (1714-1788) when he wrote his ‘Essay on the True Art Of Playing Keyboard’. (Carl Phillipp Emanuel Bach, Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments, Translated and edited by William J. Mitchell. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1949) Whilst this may not be a text for every keyboard player today, if you wish to fully appreciate the finer points of the Baroque keyboard technique, this is an excellent place to start. One key part of this comprehensive text is the clear instruction to ‘begin (trills), on the tone above the principal note’. What is of equal importance is that the elegance of the delivery is key to competent performance. Below is the table is written out by JS Bach that appears to have been the basis for establishing a good practice at the time.

In this table, there are more than the ornament that today we would recognize as a trill. It was not uncommon for Baroque composers to consider the ‘mordent’ also as a kind of trill too. A combination of these ornaments was recognized as a vital component in the musician’s armory during this period of musical history. Just as the equal temperament scale enabled a new harmonic unification of Western Music, this tablature alongside the texts coving ornamentation, helped establish agreed practice amongst musicians. What you can see in the table above is that the methods of notating trills were complex and certainly not just the alternation of two notes in rapid succession. Each of these ornaments forms an integral aspect of the piece and the performance. They are intended not only as a display of fluent technique by the instrumentalist but florid, elegant decorations to the melodic and harmonic content of a composition. Ornamentation was an essential part of Baroque musical composition, not simply an afterthought.

Even though tables and texts exist to guide the performer about the delivery of trills and other ornaments, the fact remains that conventions varied not only from country to country but also across time. The burning question of appropriate taste in the Baroque period is an almost unanswerable one, but musicians of the time would have been well aware of what was considered good taste and have the facility to interpret and add ornamentations in all their performances.