Riley B. King was born on September 19th, 1925 in Berclair, Mississippi, a small unincorporated community in the heart of the Mississippi Delta. In other words, the child we would later call B.B. was born black at the height of Jim Crow, inside of the poorest (and, arguably, most overtly racist) state in the country, and grew up there during the Great Depression. Now throw in the fact that he was also orphaned at a fairly young age—his mother died when he was nine—but don’t end the story there, because there’s a catch: the struggles of B.B.’s childhood weren’t even uncommon. Countless thousands of black kids born in the Delta in the 1920s lived the same story. Thousands today, to a greater or lesser extent, still do.

It would be inane to say this is an “improbable” beginning for an international superstar, and nobody with a rudimentary knowledge of the history of music would be surprised that racism, grinding poverty, and personal tragedy can be the crucible for a groundbreaking musical artist. None of that is worth saying. But maybe it is worth saying that young B.B.’s life was considered worthless to policymakers, social elites, and pretty much everyone with social power who wasn’t part of the civil rights movement. Only scholars talk about B.B.’s uncle and namesake Riley, who disappeared as a child, or B.B.’s brother Curce, who died at age two, or even his mother Nora Ella, who died of an undiagnosed but most-likely-treatable disease at 31. B.B. came from what had been designated a disposable community—one that was, in the eyes of the middle- and upper-class white culture surrounding it, immune to tragedy by virtue of being widely considered beneath tragedy.

When the surrounding culture teaches people that they don’t deserve the narrative arc of a dignified life, history tells us that they innovate outside of that culture and find new narratives. One of those creative outlets was the blues. It would be an understatement to say that B.B. mastered it. It would be closer to the truth to say that he refined it. He wasn’t the only major blues musician of the twentieth century, of course—that’s the century that defined the blues, and there were literally hundreds of greats—but the world-weary, brassy roar of his voice and the intricate dance of his custom Gibson ES-355 aren’t just a signature sound. They’re the John Hancock at the top of the genre’s declaration of independence.

“I can play [guitar] because I can make a rock move,” John Lennon told Rolling Stone in a 1970 interview, but “if you would put me with B.B. King, I would feel really silly.” Lennon’s comment wasn’t unusual; King reliably appears in the top 5 or 10 on any great-guitarists list, and his absence from such a list immediately calls its credibility into question. So it’s a testament to King’s generosity that it wasn’t long after he became a household name that he started focusing on collaborations with other artists both within and beyond the blues genre. But he did it without changing his own sound—something he very seldom did over his seven-decade career, and never dramatically, and never for very long. His final 2014 concerts included songs that he’d been playing for over 60 years, and in more-or-less the same style. In an industry obsessed with novelty and self-reinvention, that kind of simple principled inertia tells a story all its own.

1941: King Biscuit Time

By the time he was 15, Riley’s mother and grandmother were both dead and he was an indentured sharecropper on the farm of Edwayne Henderson, earning $2.50 per month working an acre of cotton. He’d shown some talent playing religious music in his grandmother’s church, but there was no reason to believe he’d ever make a living at it. But after a long day’s work in the fields, he—like a lot of other black teenagers—turned on the radio and tuned in to King Biscuit Time, listened to the blues, and dreamed.

In 1943, he achieved a respectable income—and was even deferred from service in World War II—because he could drive a tractor. He got married (to one Martha Denton) and settled down to a steady pay check.

But in 1947, his white employer’s tractor broke on his watch and, having no way to pay for it, he had to flee to Memphis. Suddenly his old fears—and his old dreams—mattered again.

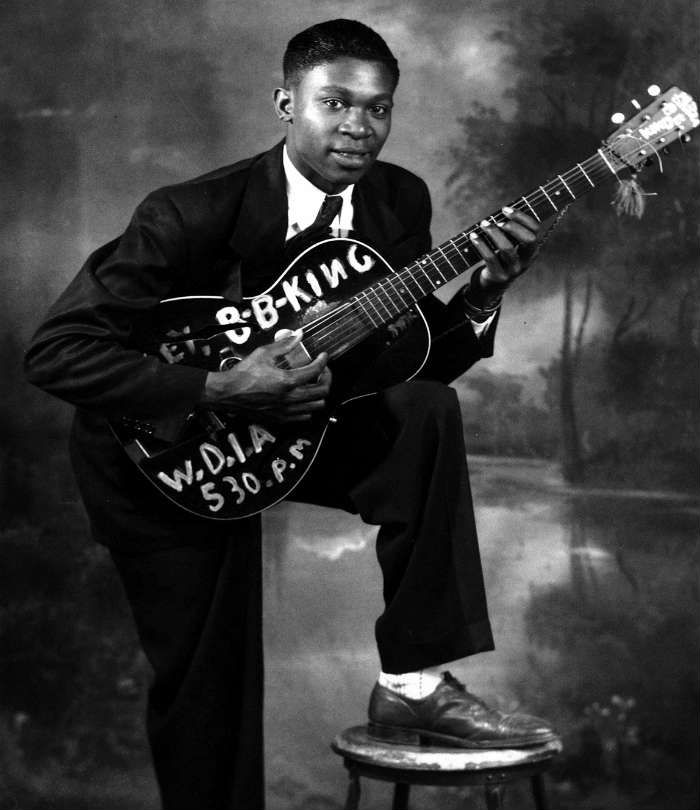

1949: The Beale Street Blues Boy and Miss Martha King

Up until his early twenties, Riley had not lived what you might call a very privileged life and he’d had few opportunities to try his hand as a professional musician. His luck was about to change thanks to the intervention of his older cousin Booker T. Washington White, better known as Bukka White, who had achieved considerable success in Memphis as a blues musician; he’s best remembered today for “Fixin’ to Die Blues” (1960), which achieved some measure of mainstream exposure after Bob Dylan covered it on his 1961 debut album, but even in the 1940s he’d become a major figure on the Memphis scene.

With White’s intervention Riley was able to get a job as a Memphis radio DJ and part-time musician, going by the handle “Beale Street Blues Boy.” In time that was shortened to “Blues Boy,” then “B.B.,” and Memphis listeners soon knew him by the name he’d carry with him for the rest of his life: B.B. King.

Before long, B.B. was able to follow in his cousin’s footsteps and release some radio singles (writing and recording the first, “Miss Martha King,” in honor of his wife). None of them did particularly well outside of Memphis, but they helped him establish a track record in the blues community. Sebastian Danchin’s Blues Boy: The Life and Music of B.B. King quotes one auspicious Billboard review: “Southern blues shouter may have talent, but he’s obscured here by loud and loose small combo orking.”

The four singles also gave him material to promote on a small regional tour. At one infamous gig in Twist, Arkansas, two men fought over a woman and nearly burned the place down. The woman’s name was Lucille and B.B., who learned several important lessons from the incident, gave his guitar—and all of his subsequent guitars—the same name.

1951: “Three O’Clock Blues” Released

B.B.’s first successful single was a cover of Lowell Fulson’s “Three O’Clock Blues.” B.B.’s version hit #1 on Billboard’s R&B charts and immediately made a national star out of him. Although he did not know it at the time, he would never again know what it was like to be an unsuccessful blues musician.

1956: Big Red on the Road

By the time his first studio album (Singin’ the Blues) came out in 1956, B.B. already had one of the most rigorous tour schedules in the business—his marriage to Martha King, which collapsed in 1952, was an early casualty of that—and five consecutive successful singles from the album broadened his repertoire considerably.

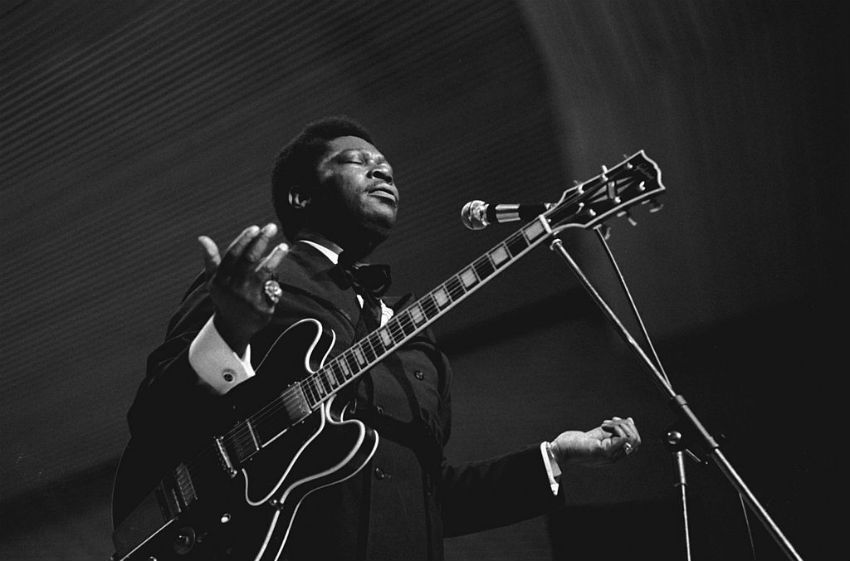

1964: King of the Blues

B.B.’s Live at the Regal (1964) was his first major live album. Recorded at Chicago’s legendary Regal Theater, it established B.B. as a world-class live performer and is widely considered one of the greatest live albums ever recorded in any genre. With its release, B.B. had gotten as popular as a black blues musician could be. White audiences were still largely out of the loop, but the blues community had thoroughly discovered him—and his standing reservation on the Billboard R&B charts, and his steady success on tour, proved it.

1970: “The Thrill is Gone”

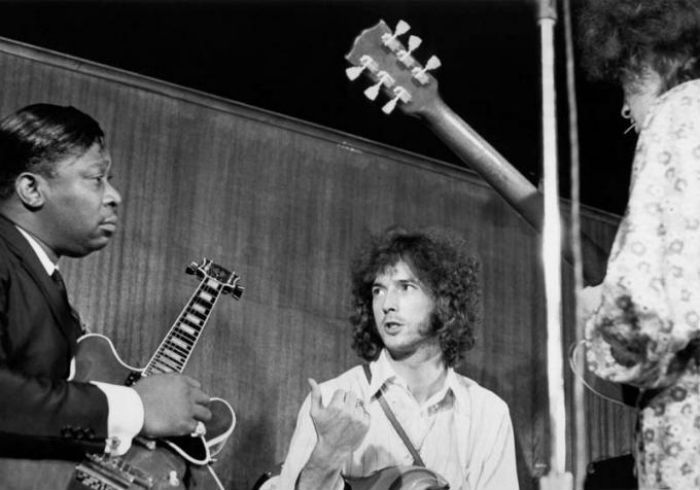

B.B.’s popularity with white audiences may have increased when John Lennon and Mike Bloomfield drew their own fans to his work, acknowledging him to be a far superior guitarist to either of them. Bloomfield—of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, a white band that played blues standards with considerable crossover success—went so far as to describe his own act as a weak imitation of B.B.’s style. But he wasn’t the only imitator; Jimi Hendrix (with whom King would famously jam at New York City’s Generation Club in ’68), Carlos Santana, and Eric Clapton all initially patterned their playing style after B.B. King.

All that acclaim from fellow musicians would have been enough to give B.B. some crossover appeal even if he wasn’t on the verge of releasing the biggest single of his solo career, but “The Thrill is Gone” (1970) changed everything. Within two years of its release, he had won his first Grammy, appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show, sold out venues from Tokyo to Zaire, and fully established himself as the most commercially successful blues artist in history.

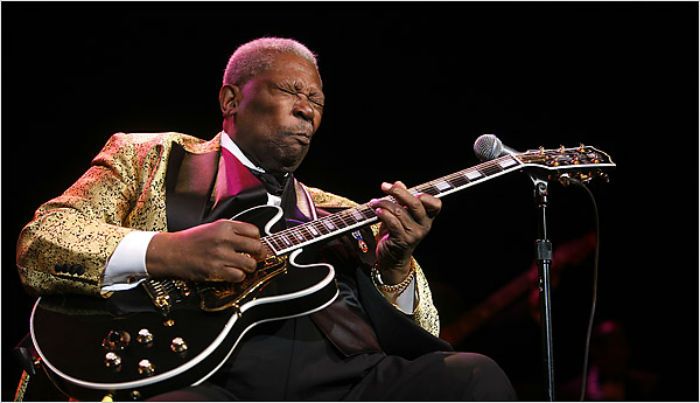

1975: A Generous Career

So once you are the most commercially successful blues artist in history, what do you do for an encore? Pushing 50 and at the top of his game, B.B. King could have plausibly retired in 1975 and he’d still be remembered today as a legend. He had no way of knowing, at the time, that he was only 26 years into what would turn out to be a steady 66-year career—and that his biggest commercial hits were still decades away.

1987: B.B. King and Friends

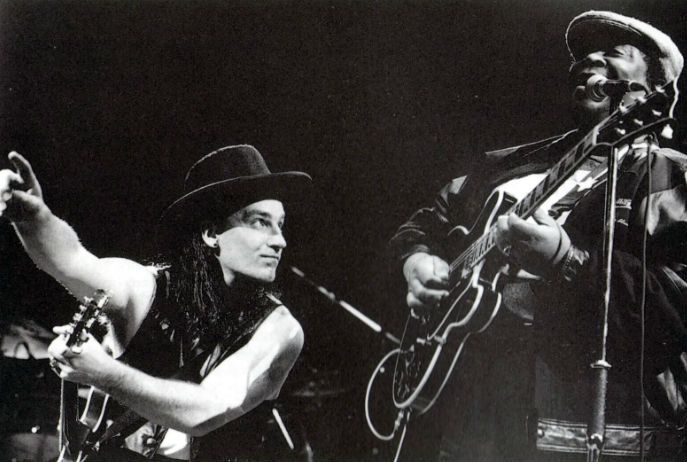

While B.B. continued to tour constantly and would go on to record dozens of studio albums, most of the press over the subsequent decades would center on high-profile collaborations. The first, with fellow Memphis blues alumnus Bobby “Blue” Bland, spanned two albums in the mid-1970s—but soon collaborations were a regular feature of his albums. He toured with U2 for four months in 1989-1990, where they played 47 shows and collaborated on several original tracks that have entered both B.B.’s repertoire and U2’s.

His most high-profile collaboration came in 2000: an album-length concept album, Riding with the King, that saw B.B. King and Eric Clapton team up to take on a century’s worth of blues tracks. For Clapton, it was an opportunity to finally work with the electric guitarist who had set the definitive example for him. For B.B., it was an opportunity to present his work, style, and voice to a new generation of listeners. Riding with the King won a Grammy, was certified double platinum in the United States, and ultimately became the best-selling album of B.B.’s career.

But his greatest collaboration is still ongoing, and it didn’t end with his death. As a founding father of the electric blues, B.B. King has left fingerprints all over the landscape of American popular music. In addition to being in his own right an immeasurably influential figure with whom promising young guitarists will be compared for decades to come, he spent his life popularizing the musical tradition that, beyond giving birth to rock-and-roll, still thrives. And deep in the Mississippi Delta’s own Indianola, where young Riley B. King picked cotton and drove a tractor so many years ago, a museum bears his name—representing a tradition, and a sound, that has traveled the world and still come back home to roost.