Even if you have not come across the term minimalist about music, the chances are you have listened to minimalist music. Since Michael Nyman coined the term in the late 1960s this genre of music has become incredibly popular.

Not only does minimalism fill our concert venues and opera halls, but it has entered pop music and the world of film.

In part, the reason for the success of minimalism is that it is accessible music that is mostly tonal and highly rhythmic. These two elements alone provide popular appeal.

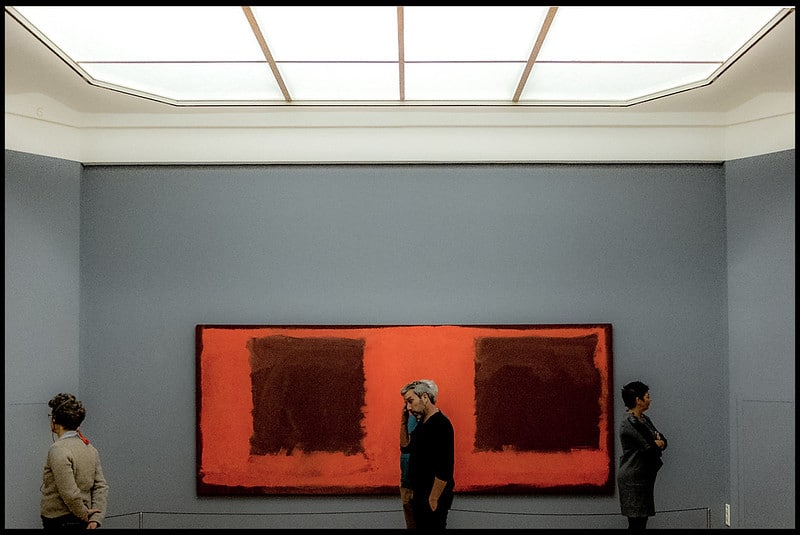

In a similar way to the minimalist art world, the origins of the genre stem from the USA. This genre of art often exhibits abstract geometrical patterns or shapes that appear simple, or naïve.

Look at the paintings of Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, or the sculptures of Donald Judd to get a flavour of this art movement. It is useful as the characteristics you hear in minimalist music in some ways mirror the world of painting and sculpture.

Characteristics Of Minimalist Music

The pioneers of minimalist music should include composers such as Louis Hardin (Moondog), Terry Riley, Philip Glass, Steve Reich and La Monte Young to name but a few.

What we hear emerging in these early forays into the genre are many of the characteristics that would become fully established as minimalism took hold.

The pieces composed by Moondog from the 1950s for example, centre their focus on slowly evolving rhythms over regular pulses with contrapuntal elements.

Frequently unusual time signatures were used bringing added rhythmic interest but the music remained broadly tonal.

Repetition of ostinato (short rhythmic or melodic phrases), would form a central role in the minimalism to come. Where this became ingenious was in the way it was and indeed still is used.

To clarify, there is a technique used by many composers of the genre called phasing or phase shifting.

It sounds simple, but essentially what happens is two often identical patterns, phrases start sounding together and gradually by changing the speed they move out of phase.

This creates a hypnotic transformation in the music that simultaneously generates subtle changes in the rhythmic emphasis, altering the way your focus is drawn.

Just as the rhythms evolved slowly over sometimes extended periods in minimalist work, the harmonic progression, if there was any, also revealed itself gradually.

A common device is to simply change from a major chord into the tonic minor (ie: F major to F minor). There is no harmonic preparation just an unannounced change.

It is straightforward in principle, but composers carefully time these tiny changes to align with large structural points in the music, not by chance.

At times, when you engage with a lengthy piece of minimalism, it can feel as if the composer is testing your endurance. If you have enjoyed a diet of more traditional Classical music, minimalism can be a challenge some cannot abide by.

The influence of Gamelan (traditional Balinese music), and to an extent African traditional music, is evident in some minimalist compositions. This can be heard in different ways.

The more obvious might be in works like Steve Reich’s ‘Drumming’ (1970-71), ‘Music for Pieces of Wood’, (1973), where the emphasis is purely on rhythm, not melody or harmony. As a composer, this presents quite a challenge.

A further link is with the homogeneity of minimalist ensembles. By this, I refer to pieces that are just for pianos, or only clarinets, or male voices. This reflects a similar homogeneity in Gamelan music.

There is of course also the strong use of ostinati in both African and Balinese music that further strengthens the connection to minimalism.

This is by no means the limits of influence from music of other cultures. In the works of Terry Riley for instance, Indian music has made a significant contribution to a number of his works that continue to embody his wonderfully unique philosophy.

What you will not uncover in numerous examples of minimalistic music is extended melody or elaborate, fast-moving harmonic schemes.

Instead is it the elaborately interlocking rhythmic patterns that serve as the primary driving and unifying force within the music. That is not to say that melodic interest is absent.

With a strong nod toward Jazz, Steve Reich elegantly captures a series of New York moods or landscapes in his ‘New York Counterpoint’ from 1985.

Here we hear not only melodic ideas that would not seem out of place coming from the clarinet of Benny Goodman, but dancing ostinati that are very compelling.

Reich’s choice of ensemble is nine clarinets, which include a pair of bass clarinets. If you enjoy this piece, you might also like to try ‘Electric Counterpoint’ (1987) which is scored for 12 electric guitars including two bass guitars, or solo electric guitar and tape.

Whilst it is always evident to me when writing these types of articles that there are many worthy composers I do not mention, I have to draw focus to those I feel are for me most influential within the genre.

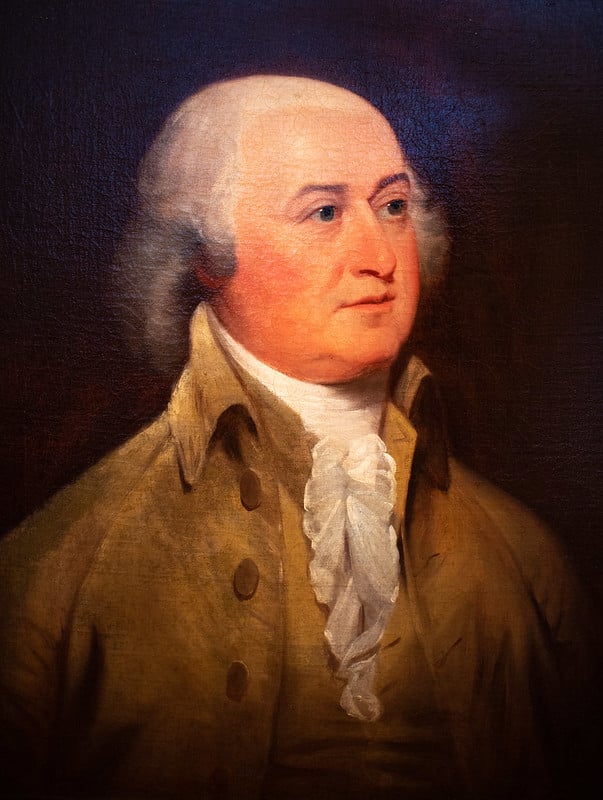

John Adams is one such composer. Adams is another American born minimalist composer but one who in my opinion, has carved a very different compositional path from many of his contemporaries.

In choosing from almost any of Adam’s extensive compositional catalogue, you will hear the traits of minimalism yet there is much more.

What stands out for me is not just the consistent originality of form and rhythmic device but Adams’s richly diverse use of harmony.

In addition, the way John Adams scores his music is truly extraordinary conjuring textures and sonorities from his players in highly ingenious ways.

Two outstanding examples of this are ‘On The Transmigration of Souls’ (2002) and ‘Gnarly Buttons’ (1996).

In John Adams’s music, we witness his successful fusion of minimalism with Jazz, popular culture, and the western classical tradition in ways I have not heard elsewhere.

Perhaps the biggest name in the ever-expanding world of minimalism is Philip Glass (b. 1937). His music has clarity and elegance to it that exemplifies many of the characteristics of the genre.

Even though the composer himself never willingly aligned with minimalism the sonic universe of Glass gives more than a passing glance in that direction.

His music encompasses a gigantic range of pieces from film to opera to solo piano works. Glass’s music continues to be immensely popular today.