When we are describing music there are often several categories of description that are commonly used. These include but are not limited to, melody, harmony, timbre, texture and structure. Each of these words draws particular attention to certain key aspects of almost any musical composition and offers the opportunity to draw insight.

Musical Counterpoint

Musical counterpoint falls broadly into the category we call ‘texture’. As you will have guessed, texture in musical terms refers to elements of a composition that are described as spikey or smooth. Other words are more technical and accurately express clear musical features that relate to the texture. These are what I loosely call the ‘phonics’: homophonic, polyphonic and heterophonic. These, in turn, mean, melody with accompaniment, many melodies at the same time and melody plus accompaniment and possibly a second melody or descant. In amongst all these comes counterpoint.

The origins of the word and a solid clue to its meaning derived from the Latin words ‘punctus contra punctum’. In essence, this phrase means point against point. The word point refers to a musical note, thus a single voice or melody combined or added to another can be considered to be a counterpoint. It is considered by some that the words counterpoint and polyphony are virtually interchangeable if these definitions are agreed. It may be helpful to simply think of two independent but musically related melodies sounding at the same time. This is counterpoint.

Counterpoint has a history that stretches bay as far as the 9th Century. As far as we can know, this is when the idea of counterpoint began to be more fully explored and it evolved to its pinnacle at the beginning of the 17th Century. It is perhaps at this stage of in the history of counterpoint and its development that its use becomes more familiar to us in the great works of the late Renaissance and early Baroque composers. Consider the remarkable compositions of Byrd, Lassus and Palestrina who set in place musical standards of counterpoint that have never been surpassed.

As is often the way in musical history the formalisation of a musical concept is attempted, and counterpoint was no exception. The Austrian composer and theorist Johannes Fux was a key figure in the formalisation of counterpoint. He was a court composer and later Imperial choirmaster (1715), at St Stephen’s Catholic Church in Vienna. Fux’s output was considerable ad included 14 oratorios, 80 masses and 20 operas. His academic text titled ‘Gradus ad Parnassum’ (1725) was his attempt at establishing formal rules for counterpoint and was used to instruct young composers.

This, in turn, led to the distinction between strict and free counterpoint. The idea was that the student diligently leaned and applied the rules of strict counterpoint, tutored by a compositional master until they reached the lofty heights of free or composers counterpoint where they could compose more freely whilst maintaining the underlying principal’s strict counterpoint.

An additional feature common in contrapuntal music is that of imitation and cannot be overlooked in this article. Imitation can be thought of as a single voice or melody beginning a composition followed by the second voice sounding an exact or almost exact copy of the first. If the imitation is a strict one then the music can be considered to be a ‘canon’. This musical device was immensely popular throughout the Renaissance and Baroque periods of music; one overused example would be Pachelbel’s Canon in D.

Counterpoint did not vanish from the compositions of the later composers but the musical emphasis changed and with it the compositions that were created. From the polyphonic complexities of the Baroque the composers, those who took up the creative torch in the Classical period opted for clarity and form in ways that might have appeared stark and limited to their predecessors. Counterpoint continued but under a whole new set of rules and expectations. As a musical device, counterpoint is regularly employed by contemporary composers too, although this is often termed ‘linear counterpoint’ that focuses on thematic and single strands of texture that includes rhythmic relationships too. The works of Bartok are a good starting point for further exploration of this point.

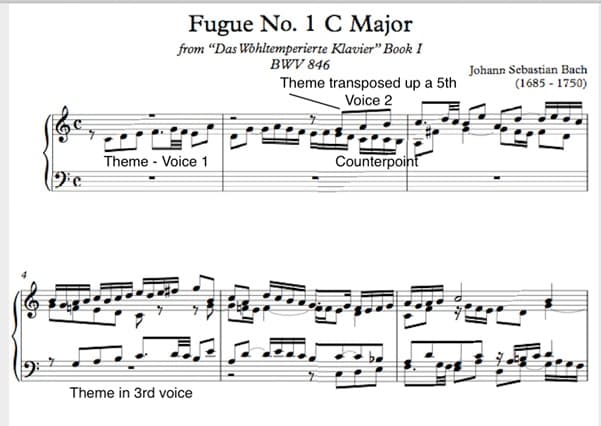

It may be helpful following this lengthy exploration of the ideas surrounding counterpoint to see some examples of what this means in practice.

What you can see in the above, very famous example from Bach’s ‘Well-Tempered Klavier’ (Book 1), is both ‘canon’ and ‘counterpoint’; the results of which create a complex polyphonic texture. This, as you can read in the title, is not simply a canon but a more developed version of this musical form; the ‘fugue’. In this particular fugue, Bach elects to write for four independent ‘voices’. The entry of the first three I have marked on the score, the fourth coming in bar 5, beat 3 (second half). At the point that the second voice sounds the original theme, the first voice begins a descending line using new musical material in contrary motion to the second voice. By the time the third voice enters the second voice is now using the same material as the first was whereas the first voice has yet more new material to play. The Baroque fugue and especially the works of Bach beautifully illustrate the elegance of the use of counterpoint. It cleverly avoids the somewhat dry, formal approach that Fux would have imposed on his eager students and instead adopts a thoroughly musical and inventive stance whilst still broadly adhering to the rules. This is, in summary, the genius of Bach and many of his contemporaries besides.