Gioachino Rossini was born in Pesaro, which was part of the Papal states, in 1792. His father Giuseppe was a semi-professional trumpeter member of a local orchestra who played in support of the French troops, while his mother was an aspiring singer. He spent his adolescence in Bologna, where he enrolled in the local conservatory at the age of fourteen. He composed his first professional opera, La cambiale di matrimonio, when he was 18 years old —its duet Dunque io son—was re-used in the first act of the Barbiere di Siviglia. He acquired international fame by the age of 20, with Tancredi and L’Italiana in Algeri. However, he retired at age 37.

Known for his rhythmic brilliance, Rossini wrote musical numbers whose frenzy marks a departure from the style of 18th century opera. His melodies have a fresh inventiveness about them, and a profound attention to orchestration and harmony—in high school, his classmates nicknamed him “Tedeschino” (the little german), also because of his devotion to Mozart. Rossini also earned the nickname of “Monsieur Crescendo,” mainly because of a characteristic mannerism in his musical writing. “The Crescendo degenerated into a mere mannerism with Rsossini, in whose works it is used with wearisome iteration,” reads the Crescendo entry of Grove’s dictionary of Music and Musicians.

When he moved from Italy to Paris, his style changed: his “Parisian” are more open to the Romantic influences. Studying the scores of Haydn and Mozart, Rossini mastered the art of symphony and the language of counterpoint, which allowed him to stand out not only in his arias, but also in the symphonies and in the concertati. When asked about his musical preference he remained faithful to his student-day heroes. “I take Beethoven twice a week, Haydn four times, but Mozart every day… Mozart is always adorable.”

Feel free to Subscribe to Our YouTube Channel if you like this video!

Rossini’s neurasthenia

Gioachino Rossini was known for his jovial personality “I have only wept three times in my life: the first time when my earliest opera failed, the second time when, with a boating party, a truffled turkey fell into the water, and the third time when I first heard Paganini play,” he said.

However, he suffered from neurasthenia and depression, a condition that was not recognized at that time. More specifically, during his fourth decade, he experienced a decline in his productivity., where periods of deep depression occurred alongside lassitude and insomnia. Adding to that, he developed pathological obesity and suicidal thoughts. In an academic article published in 1965, Dr. Daniel Schwartz maintains that, due to some psychological, unresolved issues with his deceased mother, Rossini’s relationship with his mistress and second wife Olympe Pelissier was sadomasochistic and dependent.

Remarkable facts about Il Barbiere di Siviglia (1816)

Originally called Almaviva, Rossini’s Il Barbiere di Siviglia was unsuccessful when it premiered in Rome, with the audience hissing and jeering throughout the whole performance. That’s because the the Romans, in fact, loved Giovanni Paisiello’s version of Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais’s play and took an immediate dislike to Rossini’s adaptation. What’s more, Paisiello himself had played on mob mentality, provoking the audience to openly voice their dislike for Rossini’s opera. Soon, however, the opera acquired general success. The role of the heroine Rosina had originally been written for a contralto, even though,because of (perceived) scarcity of contraltos, the role has been most frequently sung by coloratura mezzo-soprano or a coloratura soprano. Allegedly, Rossini wrote Il Barbiere di Siviglia in less than three weeks (he said twelve days)

His dramatic Muse

After rising to fame with a number of brilliant examples of Opera Buffa, Rossini turned to dramatic operas in 1813 and, up until 1822, he wrote a considerable amount of them, especially for the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. The main reason? his connection with Isabella Colbran, seven years his senior, the primadonna of the Teatro San Carlo. Originally from Madrid, Colbran was the mistress of the theatre impresario Domenico Barbaia prior to her involvement with Rossini. For her, Rossini composed the title role of Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra, the role of Desdemona in Otello, ossia il moro di Venezia, Armida (Armida), Elcia (Mosè in Egitto), Zoraide (Ricciardo e Zoraide), Ermione (Ermione), Elena (La donna del lago), Anna (Maometto II), and Zelmira (Zelmira).For Colbran, Rossini created the title role of Semiramide, which was supposed to disguise her fading talents. The couple separated in 1837—at that time, Rossini became involved with Olympe Pélissier— and her health went into decline after contracting gonorrhea. She had gambling issue. Even later in Rossini’s life, he idealized Colbran’s voice, technique and temperament, defining her the greatest songstress.

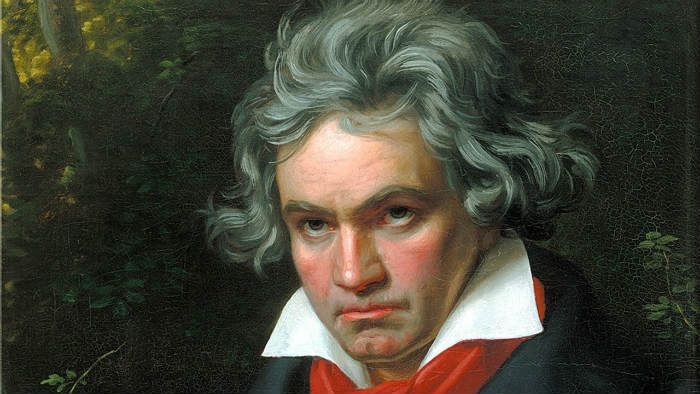

Ludwig’s sayings

“Rossini would have been a great composer if his teacher had spanked him enough on the backside” was how Ludwig van Beethoven assessed Rossini’s production. In 1822, Rossini succeeded in meeting Beethoven, who was then aged 51, deaf and in failing health. The two communicated in writing and Beethoven noted: “Ah, Rossini. So you’re the composer of The Barber of Seville. I congratulate you. It will be played as long as Italian opera exists. Never try to write anything else but opera buffa; any other style would do violence to your nature.”

William Tell’s odd destiny (premiered in 1829)

Gioachino Rossini’s final opera, Guillaume Tell (William Tell) deals with the nature and morality of political engagement in a time of oppression. The overture is, arguably, one of the most famous pieces in classical music, and Shostakovich quotes the the main theme in the finale of the first movement of his 15th symphony. However, the opera it preceded has become some sort of rarity. The reasons for the decline of William Tell’s success, however, are unclear: its excessive length is not a strong argument. Rather, Tell was perceived as a paradigm for the “grand opera” genre which had become less and less appealing after the onset of Romantic opera. Yet, it was met with raving reviews when it premiered. Donizetti stated that the opera’s second act had been written by god, since no human could compose something so sublime. Guillaume Tell was Rossini’s last opera: at age 37, he decided not to write again for the theatre.

The great Epicure

There are several anecdotes regarding Rossini’s appreciation for fine food. According to his biographers, Rossini worked as an altar boy when he was a child just so he could drink the sacramental wine left over from mass. When he went to Paris, he became close friends with chef Antonin Careme, who dedicated various recipes to him. Rossini, in turn, created arias for piano dedicated to entrees and desserts. When Wagner visited him in his country estate in Passy in 1860, Rossini allegedly excused himself repeatedly during their conversations and came back after four or five minutes. When Wagner asked for an explanation, Rossini replied that he was busy checking on a roebuck sirloin he was roasting.