A page filled with music notes can look confusing to the untrained eye. But, when you learn the names of the notes, it all soon becomes clear.

Reading music is one of the first skills each new musician needs to learn. Notes are the ‘words’ that music uses to communicate with us, and to read music, we must first understand what the notes are so we can play them.

Common Music Notes

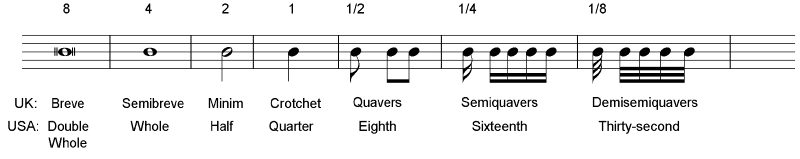

Let’s look at the most common notes found in music. They are, ranging from the longest duration to the shortest: the double whole note or breve and down to the shortest, a two hundred and fifty-sixth note or demisemihemidemisemiquaver.

In America (contemporary names) and the UK (classical names), they use different names for the notes, as you will see below. Both names are correct and can be used interchangeably.

Different Types of Music Notes

Let’s look at each of the notes used in music—we will list each individually below with a picture of each note and its associated rest.

Rare Long Notes

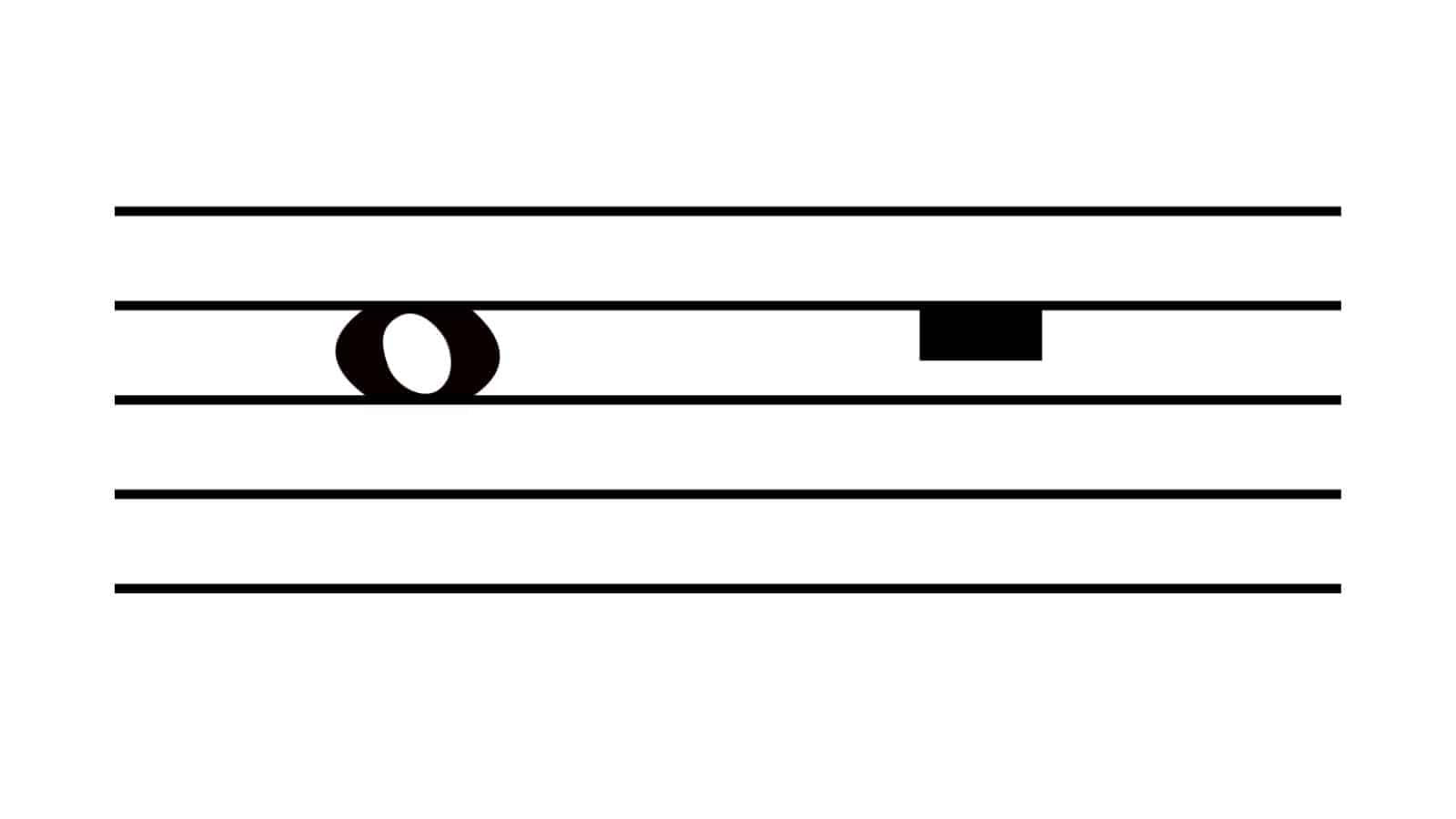

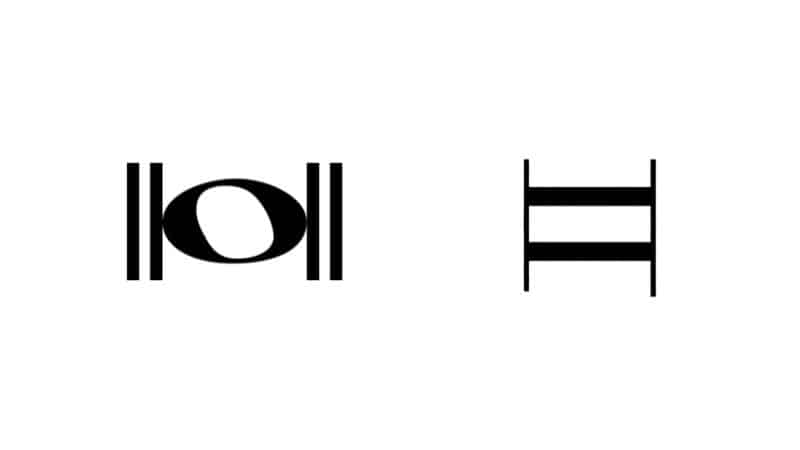

We know the longest note as a double whole note or breve. It looks like an empty rectangle with a short line on each side.

It can also look like a whole note with two little stripes on each side, lasting for eight beats or counts. Its rest looks like a block between the third and fourth lines on the stave.

Common Notes

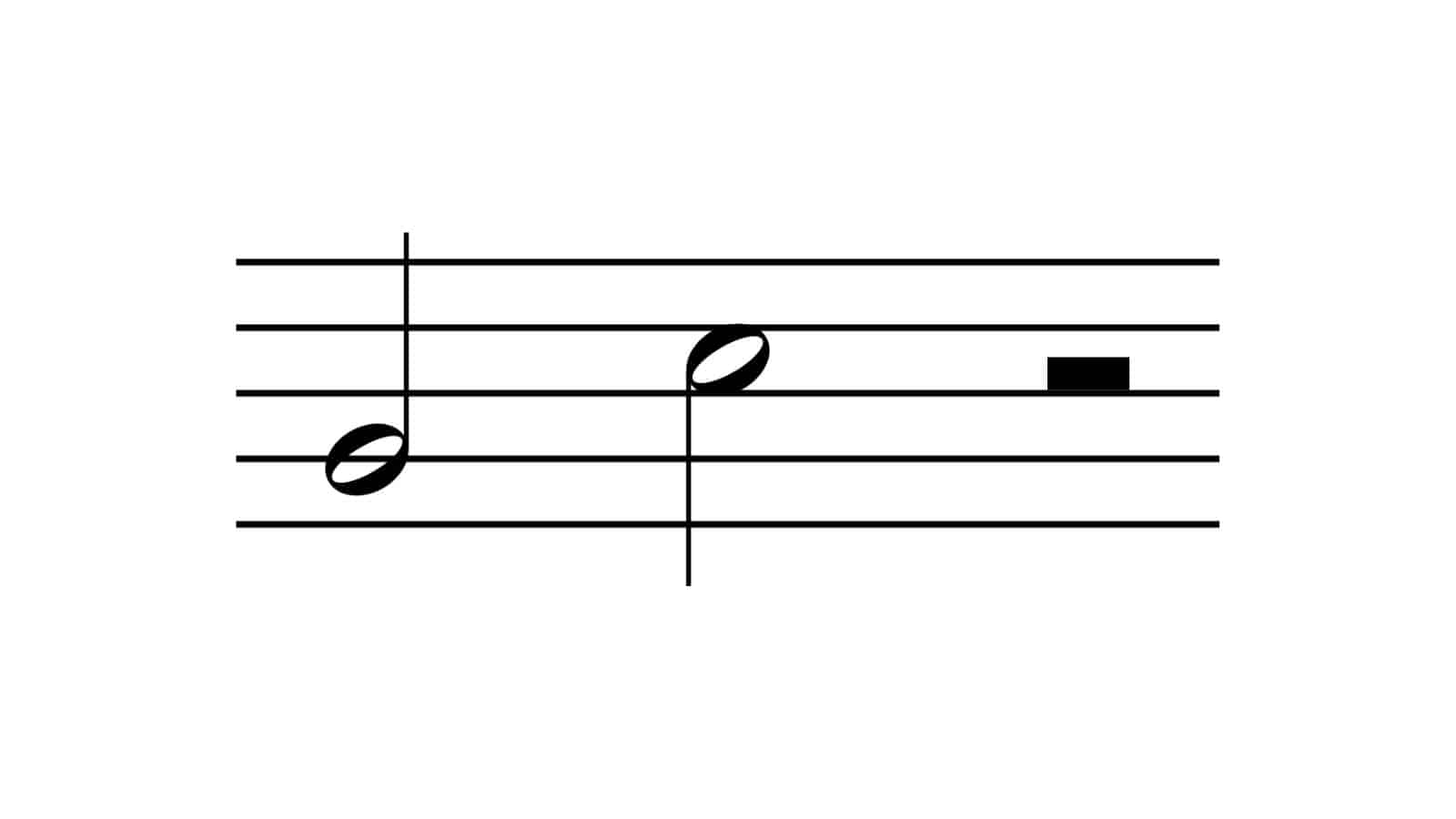

The whole note or semibreve is represented by a hollow note head (white center, black frame) with no stem or flags attached to the note. In 4/4 time, one entire note equals four beats.

The other note values are fractions of a whole note. The whole note rest is shown by a black rectangle that hangs from the fourth line of the staff (we always count from the bottom to the top of the staff).

It is equal to four beats of silence or rest. (All images are from Wikipedia unless otherwise stated).

The half note or minim, so named because it is half the value of a whole note, is shown like a whole note with a white center and black frame but has a stem (the little line on its side) attached.

The half rest sits on top of the third line and is represented by a solid black rectangle. It means that two beats of silence are needed.

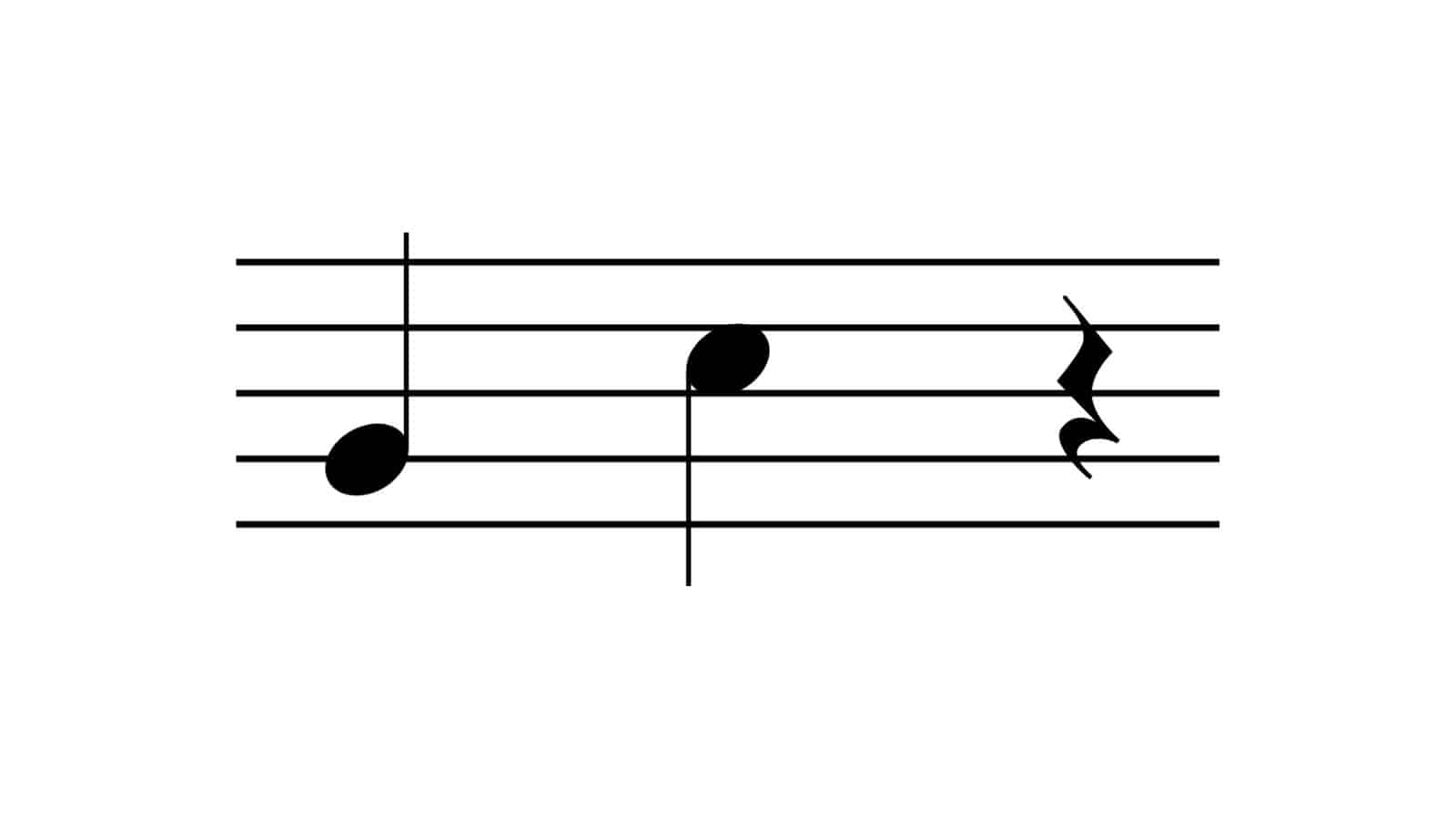

Four quarter notes or crotchets equal one whole note (semibreve). It is also half the value of a half note (minim), and now the blank note we found in whole notes, and half notes are solid.

It also has a stem attached to the notehead. In 4/4 time, it is equal to one beat. The rest looks like a squiggly line on the middle line of the stave.

A solid note head represents it with a stem, but now it has a little flag that looks like a tail attached to the stem. The flag, as you will see later on, is important because it shows us other smaller note values than an eighth note.

Eight notes are sometimes beamed (a line at the bottom or top connects them) to show that they are part of one rhythmic group.

The rest looks like the number 7 and equals half a beat of silence or rest.

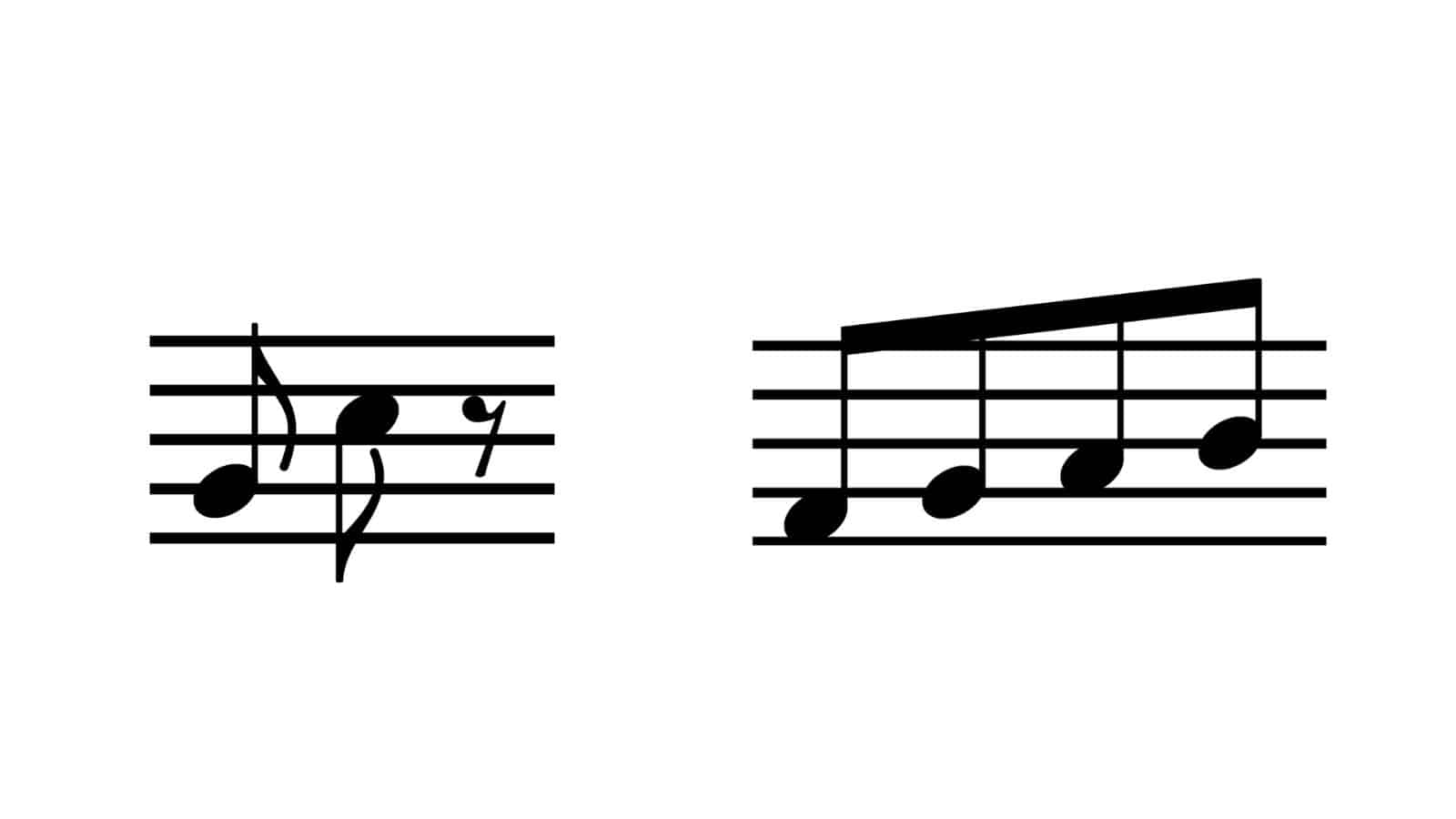

Four sixteenth notes will make one beat, and as you probably guessed, sixteen will make one whole note and eight a quarter note. It has two flags to show that it is half the value of an eight note.

Sixteenth notes are usually grouped in four notes connected with two beams to show they are part of a rhythmic group and make up one beat. The rest looks like two sevens placed on top of each other.

Yes, thirty-two of them fit into a whole note and sixteen into a quarter note. It has three flags or three beams when they are grouped.

Below you’ll see an illustration that puts all of these notes we have discussed above in perspective against a whole note (and a double whole note for good measure):

Rare Short Notes

Just when you think things cannot get shorter, we’ve got a surprise for you! We have included these special notes to show you most of the possibilities in music. Nots can also become extremely short.

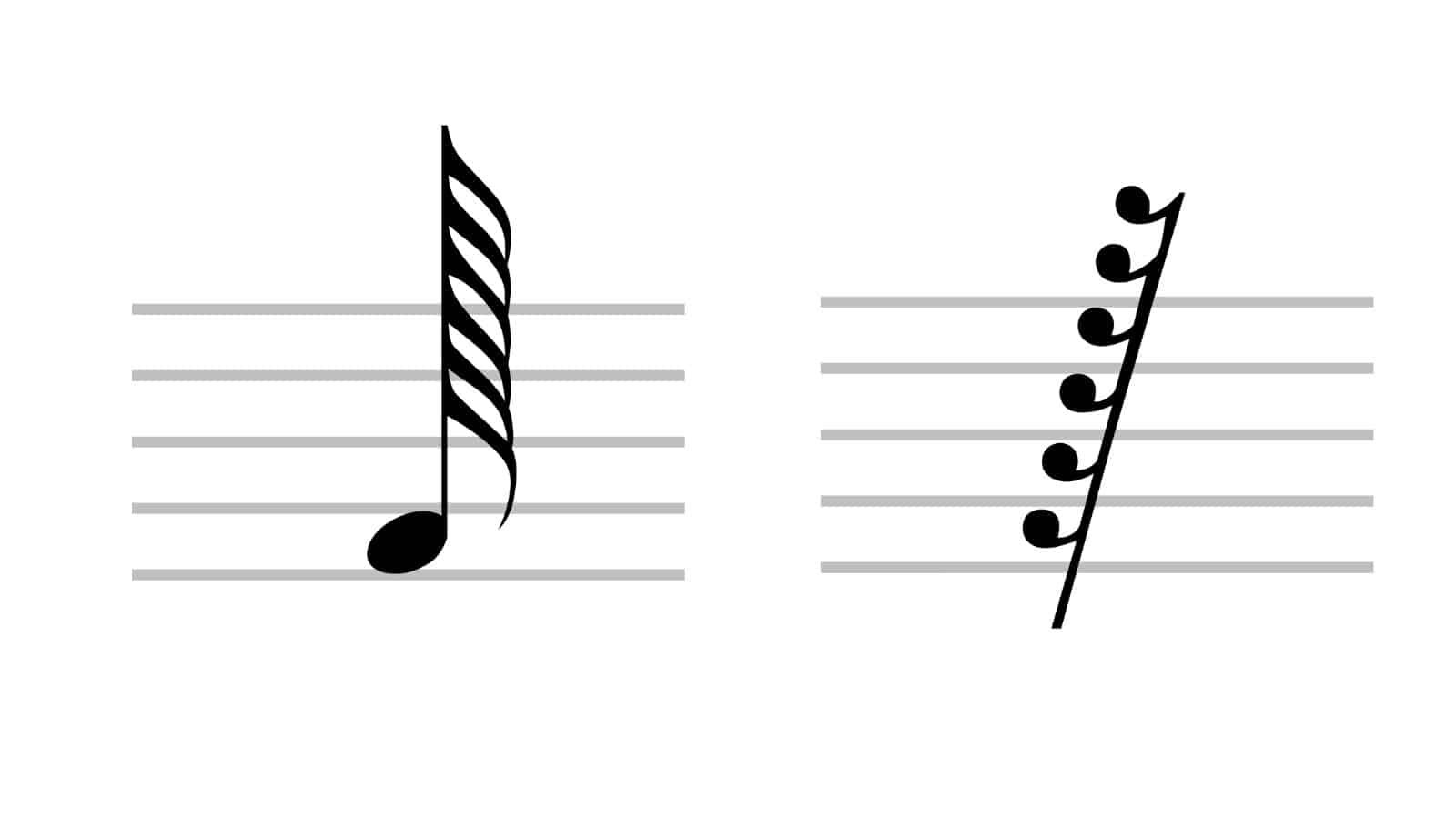

Really, really short. When you slice up the thirty-second note, you’ll get a sixty-fourth note (hemidemisemiquaver) with four flags. Its rest looks like four sevens stacked on top of each other.

The shortest note in notated music is the two hundred fifty-sixth note or demisemihemidemisemiquaver. It has six flags or beams when grouped. It is extremely rare, but it does exist.

As you can see, without knowing what the notes are, we cannot combine them into musical ‘sentences’ and express our musical ideas.

Look at this video where 40 people sing together, and ask yourself, would they be able to sing their music without musical notes? You’re probably going to say no… and you are right; they would not be able to give us this beautiful music without their notes.