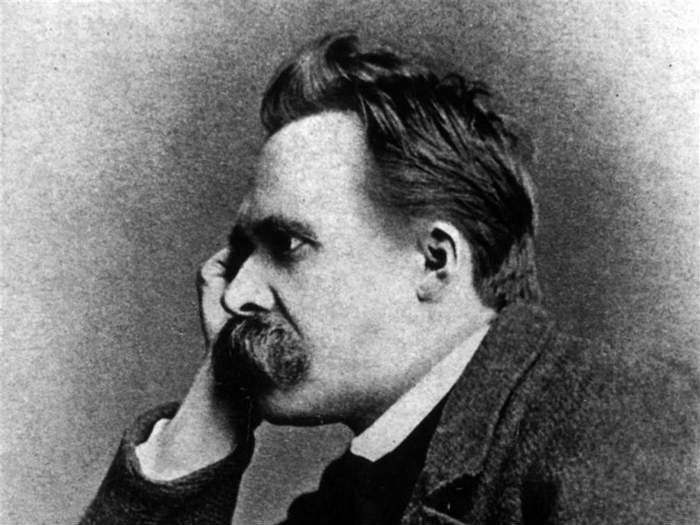

When we think of Friedrich Nietzsche, we associate that name with the current of Nihilism, works like Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the theory of the übermensch, the conflict between Apollonian and Dionysian, his shifting opinion on Wagner and concepts such as Amor Fati and the Eternal Return.

He was also known to place great importance in music and yet, not everyone has the chance to learn while studying the philosopher on a purely theoretical level, that he was also a self-taught composer, who used a textbook by Albrechtsberger, from Beethoven’s time, as a reference. Most of the activity dates back to the days when he was an esteemed philologist and professor.

In a 1863 letter to his mother, he wrote that “the great composers are inspired by an indefinable something, demonic” “the communication of this demonic,” he argued “is the highest demand that the artist must satisfy.” It was a DIM INTIMATION of the divine, and, as a composer, he wanted to command “that divine fire”. Did he, though?

Allmusic.com music critic James Mannheim defines his style “light”, “quasi improvisatory” and also “aphoristic,” a characteristic that, he argues, anticipated the style of his later philosophical writings.

“There has never been a philosopher who has been in essence a musician to such an extent as I am,” wrote Nietzsche himself in a letter dated three years before his death, and he hoped that at least some of his compositions would become known and heard since they a provided a complement to his whole philosophical project. Yet, by his own admission he valued himself as a “thoroughly unsuccessful musician.” His compositions, particularly the Sonatina n.II, are reminiscent of Bizet in terms of style.

His work was hardly well-received.

In 1871, he sent a composition for piano as birthday gift to Wagner’s wife Cosima. Rich in Wagnerian echoes, it quoted the Siegfried Idyll and, when Cosima played the piece along with conductor Hans Richter, Wagner was restless and had to leave the room. He was found lying on the floor, “overcome with laughter.”

Conductor Hans von Bulow, Cosima’s first husband whom she left for Wagner was even harsher as a judge: when Nietzsche sent him a composition that following year, actually a four-hand piano work called the Manfred-Meditation, he judged it “the most extreme piece of fantastical extravagance, the most un-uplifting and the most anti-musical…that I have set eyes on in a long time.

“Perfectly pleasant, nothing original, a pastiche” was how Ken Hamilton assessed Nietzsche’s work on BBC radio 3

He also had his theories about music, which he expressed in his philosophical writings.

In Human, all too Human, he argued that music was “the late fruit of every culture,” as it always made an appearance in the “autumn and deliquescence of the culture to which it belongs. The musicians of the Netherlands gave voice to the soul of the Christian middle ages, Handel did the same with the era of Luther and his Reformation, while Beethoven and Rossini, he continued, made the eighteenth century sing itself out. These observations led him to deny the universal quality of music itself, which, for the aforementioned reasons, just remained tied to a specific period, culture or sensibility.

Yet, in his Weltanschauung, music needed a tangible purpose: ars gratia artis was a notion he simply rejected, but, on the other hand, did he not want music to be meant for a general audience, but rather for a new kind of artist. “He did not live to see the result: modernism,” wrote Edward Rothstein in The New York Times. And let’s not forget that his work Thus Spoke Zarathustra eventually became a symphonic poem.