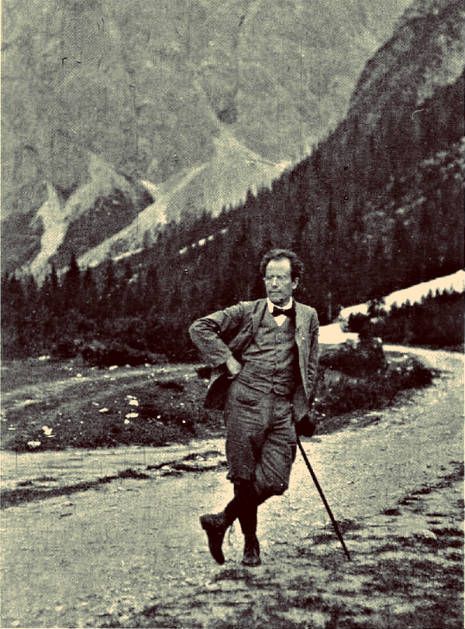

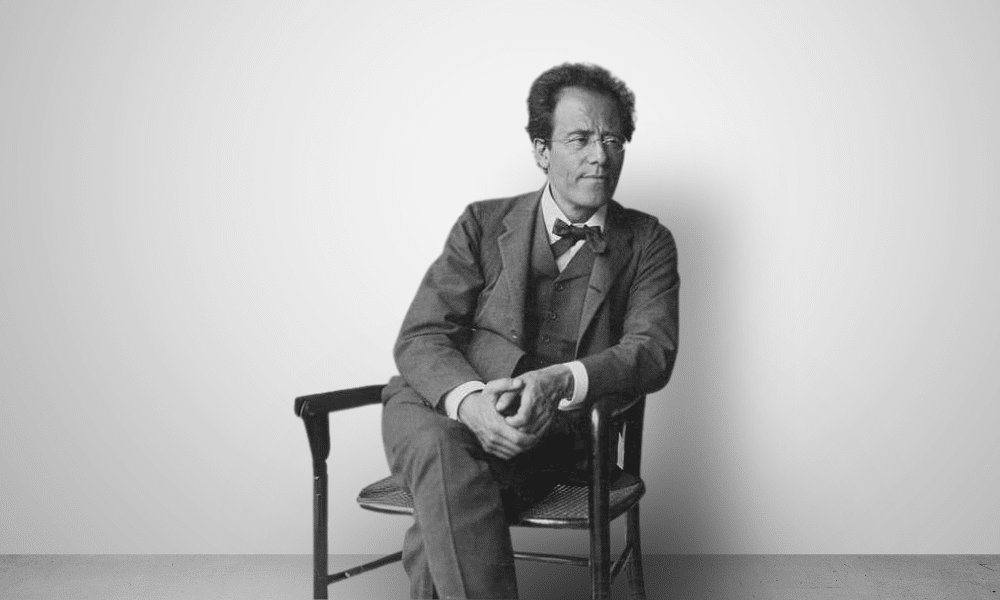

Austrian-born composer and conductor Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), was one of the greatest symphonic writers of his age. His lifetime spans a key period in musical history, the transition from the Romantic Era into that of the modern age.

It was a time of great change culturally as the hold of the nobility began to quake and the world headed towards two of the most horrendous wars humanity has endured. Mahler composed nine complete symphonies with the Tenth left unfinished at his death.

Gustav Mahler’s Symphonies

Symphony No. 1: The Titan

Mahler’s First Symphony (1887-88), nicknamed The Titan, has often been cited as one of the most remarkable first symphonies ever composed. If you aren’t familiar with Mahler’s symphonic works, then listen to this one first and I’m sure you’ll arrive at the same conclusion.

This is in part due to the sheer confidence with which Mahler delivers this monumental work. It’s a programmatic piece in which we hear folk tunes woven into Mahlerian textures that thrill and terrify.

In many ways, the symphony harks back towards an older style of composition and focus perhaps closer to that of Berlioz but Mahler’s unique voice is already evident.

Originally in a five-movement form, Mahler extensively revised the original score following the premiere and paired it down into a solid four-movement symphony. At the heart of the work is what becomes a trait of nearly all Mahler’s later works, his meditation on mortality and death.

The Third Movement, a funeral march that bewildered early audiences, illustrates this Mahlerian tendency. Mahler’s adaptation of Frere Jacques for this movement probably set many off on the wrong foot.

Likewise, the Fourth movement is an epic struggle, a stormy troubled section that travels from the darkness of F minor back to the opening light of D major that opened the symphony.

Symphony No. 2: Resurrection

As we move into the Second Symphony, we hear the distinct traits of Mahler that will last throughout his career. Composed between 1888 and 1894, this symphony was composed during one of the most traumatic periods of Mahler’s life.

1889 saw death visit Mahler, taking away from him Mahler’s father, mother, and sister all within months of each other. The effect on Mahler was understandably strong.

The key of the symphony is C minor, a key that for Beethoven was often one of the darkest and most somber. Mahler’s Second Symphony has darker moments but ultimately it is also about the strength of the human spirit and the potential for resurrection and redemption.

The composer modestly summarises the essence of this monumental work, “One is battered to the ground and then raised on angel’s wings to the highest heights.” This alluring symphony arrived at a stage in musical history when so much was in a state of flux.

The symphony is a triumph of hope over adversity and leads the way into what would become one of the most troubled and tumultuous centuries humanity had ever known.

Symphony No. 3: A Colossus

Mahler’s Third Symphony was an immediate success. Finished in 1896 it is one of the longest symphonies ever composed with six substantial and diverse movements. The opening movement is the true colossus that stretches conventional structures beyond breaking point.

Mahler carefully balances the outstanding movements by making them shorter and supplying one of the most breathtaking climactic moments in the finale.

Symphony No. 4: New Century, New Style

It is the Fourth Symphony that was completed in 1900 taking Mahler’s music into a new century. The last of the Wunderhorn symphonies, this work is modest in duration compared to previous symphonies at just under an hour.

It is also a lighter work than those that came before and those that follow including sleigh bells in the first movement and a child’s vision of heaven in the finale.

Here in Berstein’s account of the symphony he uses a boy soprano instead of the more commonly employed female soprano in the finale and this brings the movement to life in a thrilling way.

In some way the addition of the voice in the last movement has echoes of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony but in a typically Mahlerian manner.

Mahler’s Evolution and Influence

What becomes apparent by this stage of Mahler’s career is that not only is he able to bring his conducting prowess into constructive use in these symphonies but Mahler takes on the Beethovian mantle and drives it into the 20th century.

His symphonic outpourings build on the shoulders of Beethoven taking the dramatic thrust far further, vastly expanding the size of the orchestra, the harmonic framework and the sheer duration of the works.

Moreover, Mahler reflects on the increasing secularisation of Europe and addresses it by drawing attention to humanity, spirituality and hope in the darkest times.

Mahler’s symphonies embrace the world as it was and the world that was coming. He draws on the sounds of the environment he knows alongside his deeply felt emotional states that range from the ecstatic to the chronically depressed.

There is no compromise in Mahler’s music. He plunges us into his soundscape without mercy leaving us to accept or reject what he exposes us to and what he reveals of himself. The symphonies disturb and terrify us but at the same time offer hope and resolution.

Symphony No. 5: Homage to Beethoven

Mahler’s Fifth Symphony (1901-02), pays quiet homage to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in the opening trumpet melody that itself echoes Mahler’s Fourth Symphony.

The symphony is essentially in four movements with many of the anticipated features such as a funeral march that opens the work a scherzo and a rondo conclusion. It is one of the more conventionally structured symphonies, lean and taut.

The Adagietto is perhaps the most famous section of the symphony having featured in several films and often cited as being a love letter to his wife Alma. Mahler scores it for the strings alone with a harp.

Symphony No. 6: The Tragic Symphony

As we move further into the 20th century Mahler’s symphonic writing becomes evermore daring. He never shies away from unusual orchestrations that serve his purpose or transform conventional structures to support his aims.

In the Sixth Symphony (1903-04), you hear the famous Mahler hammer; a literal hammer employed to hit a solid wooden surface.

Despite the tragic tone of the final movement, this is a relatively content work perhaps echoing Mahler’s delight at having married Alma and at the birth of his second daughter.

Symphony No. 7: Night Music

In the Seventh Symphony (1904-05), Mahler slips back into the shadows in this enigmatic work that is challenging to define. The Nachtmusik that walls the Scherzo is particularly chilling, verging on the surreal at times.

The tonal scheme in the symphony is one of Mahler’s more complex, perhaps to enhance the eeriness of the symphony but almost certainly a natural evolution of Mahler’s musical language.

To further enhance this Mahler’s instrumentation is, to say the least, unconventional. Listen out for the cowbells, tenor horn, mandolin and guitar. Mahler adjusted the score following more tragedy and the untimely death of his first daughter.

Mahler had also been diagnosed with a heart condition that would eventually prove to be fatal.

Symphony No. 8: Symphony of a Thousand

By the time we reach the Eighth Symphony (1906), Mahler’s creativity seems to know no bounds. His critics and audience alike rose to the herculean challenges of this work and greeted it warmly.

In this 80-minute leviathan, Mahler returns to choral music in a symphonic framework. Against the composer’s wishes the symphony gained the nickname of Symphony of a Thousand such were the forces Mahler scored the work for.

It is an intense piece that adopts a gigantic two-part structure: part one is based on Veni Creator Spiritus; part two is based on the final scene of Goethe’s Faust. Many have felt that this work looks back to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as well as Mahler’s earlier symphonies.

Some see it as Mahler’s abandonment of the morbidity of earlier symphonies in favor of a message of hope to all humanity that through love comes redemption. Others felt that it was not a strong work at all.

Austrian critic Oscar Bie commented that the symphony was “stronger in effect than in significance, and purer in its voices than in emotion”.

Symphony No. 9: A Farewell?

The Ninth Symphony (1908-09), was the final one Mahler completed with only sketches left for the Tenth when he died. It is the final pages of the Ninth that have caused notable controversy.

Is it Mahler’s farewell to life, his resignation to his mortality, or is it an acknowledgment of transformation from one human state to something else? Could it simply be Mahler recognizing again the beauty of earthly life and the wonder that comes with it?

What we know is that Mahler certainly hadn’t hung up his boots as he was composing the Das Lied von der Erde and making major sketches for the Tenth Symphony. Mahler was also just beginning his job at the New York Metropolitan Opera.

Mahler’s approach to the Ninth Symphony is once again revolutionary both in terms of how he crafts the structure and his incredibly coloristic use of melodic and harmonic material.

Even at this late stage of his career, Mahler doesn’t fail to surprise and delight. Many of the characteristics of earlier works emerge in this symphony but through a mature lens that seems to understand and accept them differently.

There are reflections of the past and what appear to be prophetic sounds of the future, perhaps even the sense of impending war.