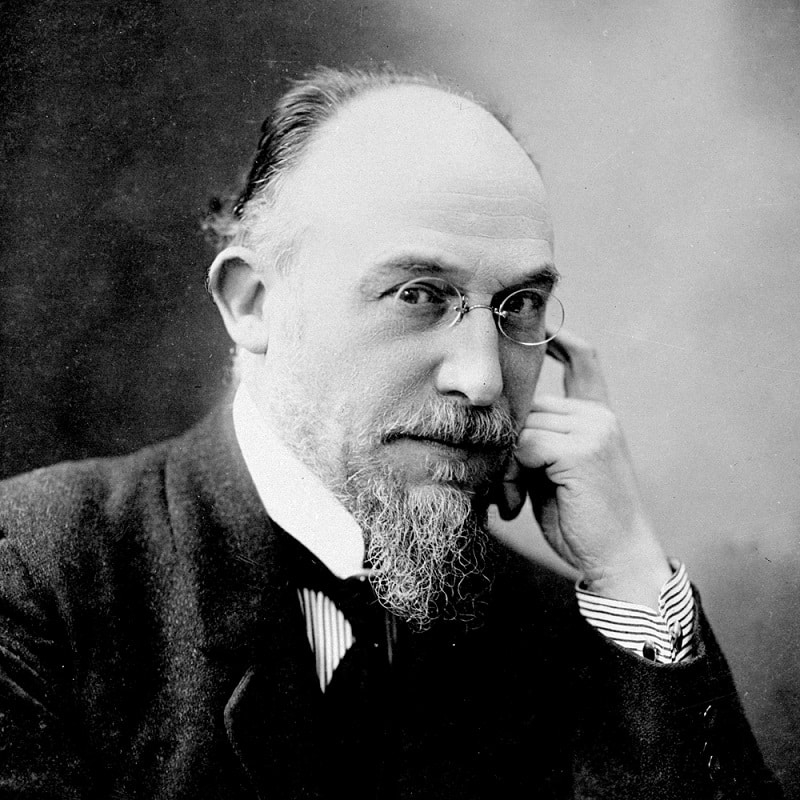

Today Erik Satie is often viewed as a curious eccentric composer who wrote some pleasant piano pieces that have now become somewhat overplayed. In fact, Satie was so much more than this and I feel it is of importance to note this before looking more closely at one of the most popular pieces he composed; The Gymnopédie number one.

Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1

Perhaps Satie’s creative uniqueness stemmed from his Scottish Mother and French Father. He was born in Honfleur, France, in 1866 and when only four years old his family moved to Paris in order for his Father to take up a new job as a translator. Satie’s Mother died when he was only six years old, the result of which meant he and his brother were sent back to Honfleur to live with his Grandparents. Satie received organ lessons whilst living with his Grandparents perhaps in order to formalise his musical skills but they do not seem to have helped the young musician very much.

In 1879, Satie was able to join the formidable classes at The Paris Conservatoire having moved back to be with his Father following the death of his Grandmother the year earlier. This was to be a memorable experience for the young composer but not an altogether positive one. His tutors at the Conservatoire were reported to have passed comments about him that were nothing short of rude and extremely unhelpful to a developing musician.

Satie was considered to be an ‘indolent’ student whose piano technique was described as ‘insignificant and worthless’. Needless to say, Satie did not remain at the Conservatoire very long and returned to Paris where he began to publish Salon music for piano. In the latter part of 1885, Satie re-joined the Paris Conservatoire for the second time but with no better results.

Actively discouraged, the composer rejected his former musical ambitions and decided, perhaps surprisingly, to join the military. Following a bout of bronchitis, he was dismissed from the army and returned to his home.

Even though Satie’s was not taken seriously by the French establishment, he slowly rose through the ranks of the renowned and celebrated. By 1892 Satie had established his own methods of composition and was following what he believed to be the best way of working. An influential group of French composers self-titled, “Les Six” adopted Satie as their inspirational leader. This ensemble consisted of some of the most influential musicians of the time including, Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Louis Durey, Germaine Tailleferre and the celebrated Francis Poulenc.

Even though Satie rejected the impressionistic movement in music, he was friends with Debussy for over three decades. Ravel also became a friend and admirer of Satie’s works which alone stands for a highly worthy validation against the voices of descent that plagued him. Later the avant-garde American composer John Cage became a devotee of Satie and his music, considering his contribution to music to be of ‘indispensable’ value. Satie also collaborated with the artist Cocteau and Picasso, creating works of immense importance to the 20th Century repertoire.

The Gymnpoédies were composed by Satie in 1888. There are three in total but for the purposes of this article, I will only focus on the first. All three are very worthy of attention and extremely rewarding to learn.

It is interesting to note that Debussy orchestrated the first and third of the Gymnopédies showing the admiration and respect he had for the music of Satie. In a more unusual incarnation the jazz-rock group Blood, Sweat and Tears also used this Gymnopédie as the basis for an album that is well worth taking the time to listen to.

Unlike Satie’s pieces titled “Gnossiennes”, the Gymnopédies are notated with bar lines. The piece is marked to be played Lent et douloureux meaning slowly and painfully. Whether this is a direct reflection of the difficulties Satie was facing is not certain, but the music is deeply pensive. The key of the music is D major and the time signature three over four, bringing a gentle lilt to the piece like a slow, difficult waltz.

Interestingly, the piece does not begin in the tonic of D, but on the sub-dominant chord of G. Satie also chooses to enrich the colour of the chord by adding the major 7th (and F#), that is a harmonic feature of this piece. This subtly softens the music almost creating the calming feel of a lullaby.

After a brief four-bar introduction in which Satie simply alternates the chords of G major 7th and D major7th, the melody that has become famous enters in the right hand of the piano part. As if reluctant to begin the melody begins pianissimo, on the weak, second beat of the bar rising from an F# a minor third to an A before falling gently towards the B, a 7th below. The melody comes to rest on a tied F# an octave lower than the starting note as the accompanying chords remain unchanged.

A second statement of the melody is heard from bar 13 with an extension that pulls the melody briefly upwards towards its starting note before a plunge downwards to a low E. Satie subtly alters the accompanying chords here, coming to rest briefly on an E minor before moving on to A minor at bar 22.

Here a new melodic idea is presented, moving again in single crotchet beats, accompanied by the same rhythmic chordal pattern below. The music gains in intensity over the coming few bars as the chords become more complex and harmonically ambiguous, coming to rest on a D major chord in bar 39. The cadence here is from the dominant minor to the tonic, giving an unfinished feel to the phrase.

The introduction begins again pianissimo, and the first part of the piece is re-stated completely. Towards the end of this short piece, Satie makes a delicate harmonic shift in the accompanying chords and melody flattening the F# in the melody to an F natural sounding over a Dm/E. The tone of the final six bars darken and the piece concludes in the tonic minor (D minor), feeling unresolved and abandoned.