The music of Ireland, like so many other countries music, is a fascinating and complex one. It takes us on a journey stretching back in time to around 500 BC. This is the time scholars believe, would have been when the Celts arrived in Ireland.

The Celts were a motley crew we categorise as Indo-European. They would have come from countries across Europe that we would recognise as Austria, Switzerland, Germany and France.

Each of these cultures and traditions would have significantly contributed to what would become known as Irish music.

It is thought that the Celts would have brought with them a selection of traditional instruments. These may have included bronze horns or trumpets of a kind, skin drums and possible early string instruments.

The horns, trumpets and drums would have been used to great effect in battle. Dating back as far as 2000 BC, a set of six cylindrical wooden pipes carved by hand in yew wood was found in County Wicklow, Ireland.

This raises all kinds of questions regarding the music that could have been heard so far back in the history of Ireland.

History of Irish Music

One instrument that has dominated the music of Ireland is the harp. This is an ancient instrument with a legacy dating to 3000 BC.

It was an instrument found frequently in Africa, Asia and Europe and one the Celts could have brought with them on their migration across Europe. The harp has remained a feature of Irish music ever since.

During the Middle Ages, the harp became a favourite instrument in Ireland, desired and admired by the nobility. If you were a competent harpist during this period of Irish history, you could make a fine living performing in the Courts of the Chieftains.

This tradition came to a terrible halt during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. Many conquests of Ireland had taken place during the 500 hundred years before but the English showed a brutal determinism that has lasting effects on the culture of the Irish.

Such was the Gaelic tradition embodied by Irish harpists that Elizabeth I ordered the hanging of any harpists and the burning of their instruments. This was all in an attempt to anglicise Irish culture and its effect on the music of Ireland was devastating.

We also know, to a certain extent, that music would have echoed through the halls of the Irish monasteries. It would have mirrored the sounds of the sung liturgy in other European countries.

Music that would have been initially performed at the interval of the octave or fifth where the sacred text and its meaning took president.

What is a departure from other cultures is the mention of a harp that 12th Century Priests, Bishops and Clergy customarily took with them to accompany a sacred song.

There are many accounts from notable members of the clergy who visited their Irish counterparts about how beautiful their performances were.

Secular Irish music has a long tradition, probably just as long as the sacred. The song is at the heart of Irish music. It is after all the most natural form of expression available to human beings.

One of the older types of song is called Sean-nós, or in the old style. These are traditional songs that are usually performed unaccompanied. The lyrics are of great importance as is the practice of melodic ornamentation, but never at the expense of the words.

Caoineadh songs are one of lament, sorrow and pain. There are understandably many of these songs from the 17th century that tells of the pain of forced emigration as well as the death of family members.

These kinds of songs were widespread once in Ireland but seem to have shifted out of favour as the 18th century wore on.

The topics for traditional songs covered the expected gamut from drinking, to love, ballads and laments. Accompaniment varied according to the instruments available, but as with the Sean-nós, no accompaniment was also typical.

Many of the instruments we associate with traditional Irish music would have been common then too including the Uilleann Pipes, the fiddle and the framed drum called the Bodhrán. With the songs came the dances including popular reels, hornpipes and jigs.

The 19th Century saw an influx of European dances that probably arrived from soldiers returning from battles on the mainland and migrant dance troupes.

Of the many Irish composers to receive a listing in the Early 17th Century Irish Chronicles, assembled by monks is Turlough Carolan. He lived from 1670-1738 and was both a fine harpist and composer of some two-hundred compositions.

Some of these showed aspects of contemporary Baroque practices but Carolan’s roots were firmly planted in Irish traditional music.

Other composers who stand out as having made significant contributions to Irish music during the 17th and 18th Centuries include, Colm de Bhailís, Arthur O’Neill, Dominic Ó Mongain and Patrick Byrne.

Patrick Byrne is thought to not only have been the last proponent of the traditional Gaelic harp but the first traditional Irish musician to be caught on camera.

The decades of oppression, rebellion and war that plagued the 16 & 17th centuries took their toll on Irish music. In 1792, with the hope of revitalizing the Irish harp, a festival was organised in Belfast.

It was a way of bringing together some of the finest harpists in Ireland and unifying some of the beleaguered traditions. 1798 saw a failed rebellion in Ireland that caused further devastation to Irish culture despite several songs written about these wars (Arthur McBride and Fare Thee Well Enniskillen).

Misfortune continued into the 19th century when the Irish potato famine struck between 1845 and 1852. It is estimated that during this period a million people lost their lives whilst a further million emigrated; many to the United States.

Sad though the circumstances were to cause emigration, this eventually led to the establishment of networks of Irish musicians in cities like Chicago, Boston and New York.

As technology advanced and recordings and broadcasts of music arrived from America in the early part of the 20th century, Irish musicians began to develop their music along new lines. The music increased in tempo and new instrumental groupings were trialled.

The 1960 and 70s saw a huge revival of traditional Irish music. Irish pubs became commonplace across England (and eventually mainland Europe), where Irish music was played to dance to.

Musicians began to expand traditional musical forms, some exploiting Classical models and performing with extended improvised solos.

The banjo, an offshoot of the American-Irish musicians crept into mainstream Irish music. Influence of Bluegrass and Country seep into the veins of Irish culture.

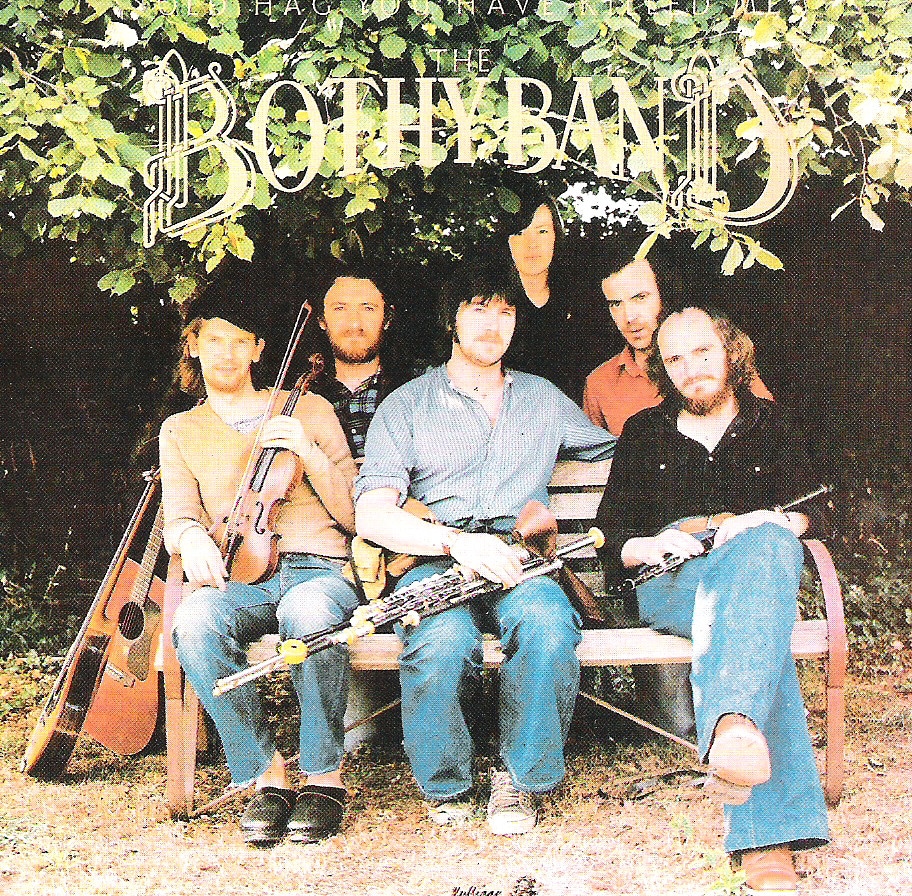

Even the piano was used to accompany songs and dances. This was quite a departure from tradition. Bands like Planxty and The Bothy Band were major exponents of this new Irish music.

In the 1980s what is now termed Celtic Fusion, pushed Irish musicians into the spotlight. Some artists blended rock, hip-hop, reggae and jazz into traditional Irish music. Some enjoyed tremendous success, others less so.

Of the chart toppers from this time think about Enya, Sinead O’Connor and The Pogues. One of the biggest names to come from Ireland and almost singlehandedly encapsulates that fusion of old and new is the band U2.

Their contribution to Irish music has been huge. Their iconic song Sunday, Bloody Sunday, highlights yet another tragic episode in the history of this culturally rich country.