The origins of western music trace back to the Ancient times of the Roman and Greek empires. Many of the customs and practices of these culturally rich centuries have built the foundations for the music that followed.

Many instruments that featured during these periods of cultural history have evolved into the ones we recognise and perform today. The division of secular and sacred music continues from those eras alongside some of the melodic and harmonic concepts that began so far back in history.

In particular, the discoveries of Pythagoras, such as tuning ratios and eventually modality, have lasted into the present day.

History Of Western Music

Where we continue the narrative of western music is as we reach the Mediaeval Period. Contrary to many opinions about this colourful era of music, this was a time during which a plethora of important developments occurred.

The time under consideration is vast, stretching from the fall of the Roman empire up to the Renaissance period in the early part of the 14th Century. Where we arrive at familiar territory around the 6th Century and Pope Gregory I.

At this stage of musical history, the codification of chants began in earnest alongside the classification and organisation of musical material. These became the eight church modes each serving a particular purpose in sacred music.

This was a crucial step in the development of music that had significant ramifications for all music that followed.

Tropes, (a section of melody or liturgical text added to an existing chant), became a dominant feature by the 9th Century allowing singers to add a more personal level of expression than before.

From the distinctive sound of Gregorian chant came the revolutionary concept of polyphony. Chants were essentially a monophonic form of music, but as the new millennium dawned a second voice was added to the existing one usually at the interval of a fifth or a fourth.

The interval was there for the purity of sound but also corresponded to the natural range of male voices. This in turn gave rise to the independence of melodic lines and greater rhythmic freedom as the century travelled on.

By the 12th century, France was making advances in music notably through what came to be known as the Notre Dame school.

Composers such as Leonin, who assembled the Great Book Of Organum, containing a range of two-part pieces for the entire sacred calendar, and his successor Perotin.

What Perotin achieved was the introduction of two, three and four additional vocal parts in his music added to the existing cantus firmus held in the tenor part. True polyphony as we understand it today was born.

It was also during this period that the motet evolved from the experiments with polyphony and a type of music referred to as the conductus. (A Latin text set in up to three parts usually for ceremonial occasions).

Music transforms further as the 14th Century arrives. From the Ars Antiqua (Old Art), evolves the Ars Nova (New Art). The Ars Nova period heralds a major departure from the conventions of the previous generations.

During this time frame, we hear developments in all elements of music. Rhythms and metres become more varied and complex including duple and triple time.

In the harmonic language, we can see composers such as Guillaume de Machaut incorporating softer intervals such as the third and the sixth instead of the open, ambiguous fourth and fifth.

Through the motet, the relationship between text and music grows closer with each influencing the structure of the other. Machaut’s works make sophisticated use of the isorhythm, (the employment of a single rhythm, usually in one voice, that remains for the duration of the piece).

Secular and sacred music found a more equal footing during the 14th century. Secular forms often related to dances such as the Estampie or the saltarello are popular, derived from the earlier work of the Troubadours.

As with all forms of expressive arts, one era builds on the discoveries and innovations of the previous one. The Renaissance period was no exception. Dance forms taken from courtly settings governed many musical forms during this period.

The motet and the madrigal were highly popular secular forms of parallel importance to the sacred Mass. Modality established itself as the basis for melodic and harmonic composition as the distinction between secular and sacred became more marked.

Instrumental as well as vocal music took equal precedence with some astonishing developments in new instruments. These include the viol family and keyboards like the harpsichord and clavichord.

This gave composers valuable opportunities to create instrumental pieces that were ground-breaking. Music remains highly polyphonic with increasing complexity as the era progresses.

The Renaissance can be thought of as covering roughly a two-hundred-year period from 1400- 1600 with the ideas and values of the early renaissance coming to fruition in the works of the late renaissance composers.

These inspired individuals include composers like John Dunstable, Josquin des Pres, William Byrd, Thomas Tallis, Claudio Monteverdi and the unmissable, Giovanni Palestrina.

Each of these men, amongst many others, took ever more daring risks with their music. The harmonic language was richly sonorous, especially captured in the music of the late renaissance composers.

The Renaissance gives way to the Baroque Era (1600-1750) at the end of the 16th century. Baroque music, like the popular architecture of the day, was elaborate, gilded, and splendidly ornate.

It is here we meet composers like JS Bach, GF Telemann, GF Handel, Antonio Vivaldi, A Corelli and Henry Purcell. Many key developments occur during this period. Tonality becomes the successor to renaissance modality taking harmony in radical new directions.

Musical forms and textures built on the polyphony of the previous period still include dance forms but the advent of the fugue is monumentally important.

New musical genres such as opera are created with instrumental music growing ever more popular as the quality and variety of instruments expand.

The creation of the violin is one of the pivotal moments that begins to define the era thanks to the Medici family. The reign of the viol family dissipates in favour of this new, highly expressive and powerful instrument.

Landmark works such as JS Bach’s St Mathew and St John Passions; the operas and oratorios of Handel; Vivaldi’s monumental collection of concertos; the operas of Henry Purcell highlight only a few works.

Baroque music demonstrated a fresh vigour and strength of the human spirit, energised by the revitalised dramatic and expressive innovations.

From the glamour of the Baroque, music turned in a counter direction in the Classical period, (1750-1830). Here the likes of WA Mozart and J Haydn dominate the musical landscape, bringing with them structures such as sonata form, and rondo.

The clean measured melodies regularly phrased and laid over tonic-dominant harmonies structure the driving forces of this era. Gone are the mesmerising polyphonies of the Baroque in favour of homophonic textures.

Symphonies, sonatas and concertos populate instrumental music whilst opera cleanly divides into comic and serious. The mass and the oratorio keep their foothold in sacred and secular music camps respectively.

Instrumental development takes a quantum leap forward, with the piano replacing the harpsichord whilst the clarinet finds its place in the orchestra alongside growing string sections, more brass and percussion.

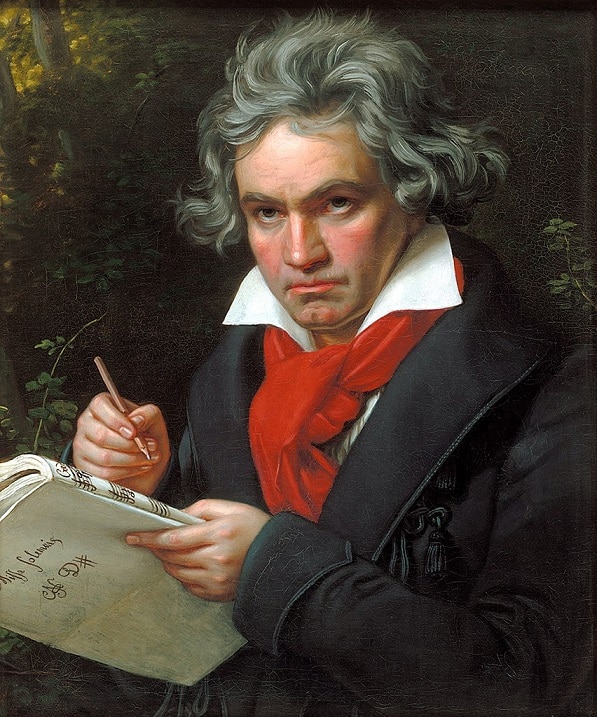

Beethoven spans the Classical into the Romantic period of music (1830-1910). He is a gigantic figure at this time pushing the boundaries and conventions established previously. Beethoven almost single handily defines this transition.

Following the almost austere qualities of Classical music, the Romantic era swerves the other way completely.

The music grows in terms of instrumental forces, structure, and scale. Harmonic language becomes increasingly chromatic to the point where tonality begins to crack by the time Richard Wagner is composing his operas.

This harmonic development allowed for ever more expansive freedom of expression in the music as characterised by the works of Schuman, Mahler and Richard Strauss.

During this period, we see the rise of the virtuoso superstar performer capable of performing pieces that demand unimaginable technical facilities. Liszt and Chopin were two examples of this as both composers and performers captivated their audiences.

The legacy of the Romantics lived on in composers like Edward Elgar, Ralph Vaugh Williams and Gerald Finzi to name but a few.

What is often termed the Modern Era takes centre stage as the 19th century closes. Tonality is shattered by the theories of Arnold Schoenberg.

His system of organising the twelve notes of the chromatic scale offers a way out of the established tonal confines towards a dissonant, angular, troubling new style of music. Schoenberg, Webern and Berg become the atonal devotees that were known as the Second Veniesse School.

Nationalism rises from the ashes of Romanticism in the powerful works of Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Sibelius and Scriabin, to name but a few. Impressionism flows from the pens of French composers like Debussy and Ravel reflecting the innovations in fine art.

In the USA, composers such as Copland, Bernstein and Charles Ives bring a New World sound to the modern landscape incorporating elements of jazz in many of their works.

Later in the 1950s Minimalism emerges shining the spotlight on composers like Steve Reich, John Adams, Terry Riley and Philip Glass.

By the 1960s electronic music has established a foothold in both the classical and popular worlds of music. Genres continue to fuse and diversify during the remainder of the 20th century.

Many forms like the symphony, the tone poem, the concerto, the sonata, opera and oratorio that look back three hundred years continue to prosper in the works of contemporary composers.

The sheer diversity of musical styles today reflects the rich history of Western music that continues to show the endless possibilities of this art form.