How Many Strings Are In A Piano

Most contemporary pianos have a range of seven and a quarter octaves. This has become an industry standard although some have more and some have less compass. That seven and a quarter octaves account for eighty-eight notes, black and white.

It would be reasonable to assume from this information that a standard upright or grand piano would contain eighty-eight strings; however, there’s more to manufacturing pianos than meets the eye.

As a young and curious pianist, I decided to remove the front panels from my upright piano to understand better how the instrument worked.

Fortunately, this minor alteration was easy to remedy, or I’d have probably been in a certain amount of trouble for my thirst for knowledge. What I discovered was not what I expected.

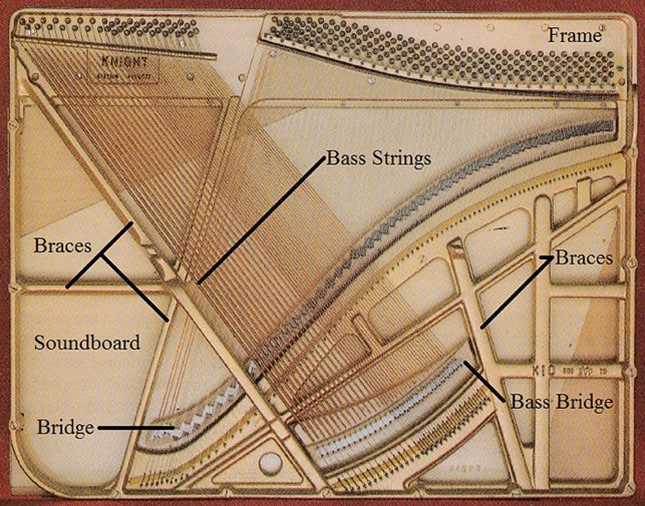

I had initially linked the number of keys to the number of strings, but this was not the case. Inside my long-suffering piano was an over-strung design. (See below)

In fact, this is the inside of the very piano I had as a young pianist, which perfectly illustrates the concept. What you see are the bass strings stretched over the mid-high strings.

This is because of the limited space available in the upright case to produce a good-quality sound.

This diagram shows that the number of strings begins to alter as the pitch of the notes rises. I recall that this change happened around C2 (an octave below middle C).

At this point the single copper-wound string became two strings, then as the pitch of the note rose, three strings. The technical term for this is scale design that I’ll briefly explore below.

Scale design refers to the unique construction and design of each piano. This includes using different length and diameter strings, referred to as high- or low-tension strings.

That directly affects the tone of the piano. The copper-winding of the strings is included in the scale design as well as where the relevant hammer strikes a string.

Where bridges are located on the soundboard is another key element of scale design. Each of these plus many additional subtleties creates the individual tone of a piano and is very important in piano manufacturing.

What this means is that it is almost impossible to arrive at a single figure in response to the title question. Depending on the scale design a piano could have 220 up to 240 strings.

This is a figure far larger than you might anticipate, but a piano is a highly complex piece of musical equipment.

If we step back in time, it quickly becomes apparent that not all pianos are created equal. The figures above for the number of strings relate to pianos with eighty-eight keys spread over a seven-and-a-half octave range.

Early pianos were not the same. Bartolomeo Cristofori, thought by many to be the inventor of the piano, made pianos with a range of between four and five octaves. If we accept the four-octave range, then that’s considerably fewer strings.

What Cristofori did was model his pianos’ internal workings on the well-established harpsichord. His early pianos used two strings per note. This would give 96 strings on a four-octave piano.

Beethoven’s pianos initially only had a six or six-and-a-half octave range, but by this time the concept of the piano had advanced considerably. The mechanics of the piano were far improved as well as its tone and overall robustness.

The number of strings varied, but as we advanced through the 19th century, the piano began to resemble the instruments of today more closely.

Manufacturers tried and tested many variations of string combinations probably with the aim of maximising tone, stability, and strength.

Over the hundreds of years of piano manufacturing the present string numbers seem to offer the optimum solution. This naturally leads to questioning why three strings at the top and only one at the bottom end of the piano.

Unfortunately, the answer to this is quite complex if one is to appreciate the whys and wherefores fully. The bass (lower) strings are single steel strings wound in copper because they can take the tension needed to produce rich, low pitches.

It could be that a two or three-string bass note might enrich the tone or bring with it some other desirable characteristic, but there isn’t room in a piano to achieve that.

Besides, the whole system of hammers would then have to be changed bringing with it more manufacturing challenges.

The upper range of notes most commonly utilises a combination of three strings. These are also steel strings under some incredibly high tensions.

They are not wound with copper. Interestingly, the group of three strings is often slightly de-tuned to create greater resonance and improve sonority.

This is hard to hear unless you pluck individual strings from a single note. It can also depend on the piano tuner. The combination of three strings offers the best sound quality and the most suitable action and touch.

Piano manufacturing is under constant review. Many leading companies employ academics to research new materials, find ways to enhance existing piano-building techniques or design optimum frames.

It’s a highly competitive market where an edge that offers the performer that special something that no other piano has could drastically alter a company’s fortune.

Perhaps as the future unfolds, there will be exciting innovations in piano design and development. Certainly, one of the most imaginative is the combining of digital and acoustic pianos.

This hybrid technology is likely to have a secure place in the instrument’s future. For now, and for the vast majority of pianos, the number of strings isn’t terribly different.

It’s worth mentioning the Fender Rhodes or Wurlitzer pianos as a finishing thought. These portable 6-octave instruments made themselves popular in the 1960s.

Unlike their cousins with strings that produce the sound, these instruments use rubber hammers to strike metal bars a little, like a rubber mallet hitting the bars on a vibraphone.