When composer John Cage wrote 4’33” (Four minutes, thirty-three seconds), it would become his most famous and controversial piece. The audience at the world premiere was prepared to listen to this piece divided into three movements. Pianist David Tudor walked out on stage on August 29, 1952, in Woodstock, NY, sat down at the piano and closed the lid.

At the end of the first movement, the lid was re-opened. This closing and opening was repeated to before the second and third movements. Instead of music performed in a traditional concert setting, the initial impression was that the audience had been subjected to silence.

The silence of the piano did not leave the audience in silence. They made their own music by their whispers that grew louder as they wondered what was going on. Some of them got up and walked out. Others shuffled in their seat, anticipating that the pianist would play something.

Cage created this work to encourage people to listen to the sounds around them. The sounds make their own music even if it is not the traditional or conventional music people are used to.

This work has prompted various discussions about silence and music. When someone is observing a period of silence, there are still sounds present such as rain hitting a window, distant traffic sounds or voices. Recordings of rain, ocean waves, and other white noise are often used to help people relax. Some people cannot go to sleep without the sound of white noise in the background.

The impact of perceived silence happens daily even without thinking about it. One of Simon and Garfunkel’s most popular songs, The Sound of Silence, describes something in each verse that disrupts silence. The interruption of the silence can be either audible or emotional.

Conventional music has rests as part of the music. If those rests did not exist, there would be no place for singers to breathe, no variety in the combination of instruments heard during a symphony orchestra or band concert, and no place in the music for a pause as part of the rhythm. But when a musician sees a rest in the score, that rest is still part of the composition and is a valid part of the overall work.

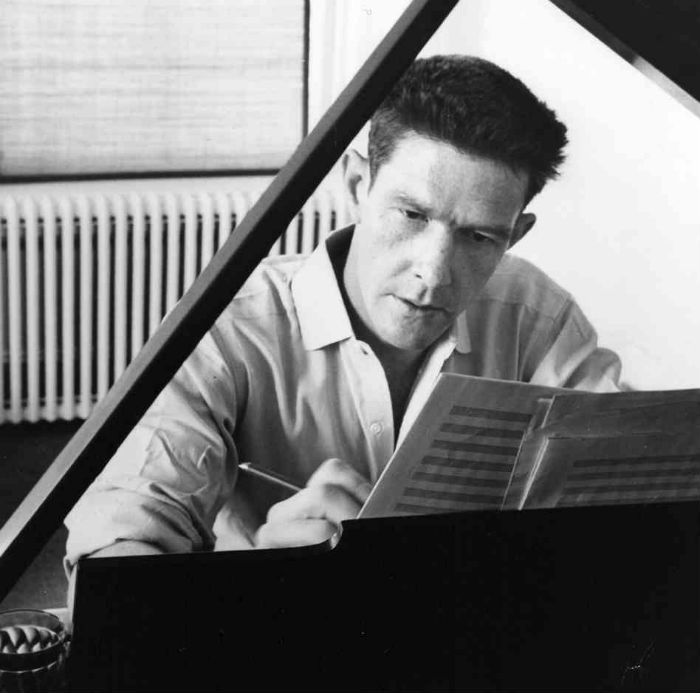

Cage (1912-1992) was a pioneer in using instruments in non-standard ways. For example, he wrote works for a prepared piano–a piano that had objects placed under some of the strings to create unique sounds. He was also a major influence in the development of modern dance along with his partner, choreographer Merce Cunningham. He was also one of the first to compose using electronics.

It was the composer’s study of Zen Buddhism that influenced his aleatoric or chance music, meaning that part of the composition is left up to chance as determined by the performers. Cage also used the I Ching to determine fixed elements in his works such as tempo and duration. Within those fixed elements, there was room for random sounds. The sounds in a house, of nature, or outside a window will not be the same from one time to another.

Although 4’33” was first performed by a solo pianist, other ensembles have also performed it. In 2004, the BBC Symphony Orchestra gave the first orchestral performance in the United Kingdom. The concert was broadcast live over BBC Radio 3. It was a challenge for the radio station because of the almost five minutes of on-air silence. The emergency backup systems had to be switched off to avoid having them fill in the silence.

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, in connection with the John Cage Trust and his publisher, C.F. Peters, put together an exhibit in 2012 in honor of the 100th anniversary of his birth. John Cage Unbound: A Living Archive was a display his original manuscripts, concert programs, photos and videos about his music.