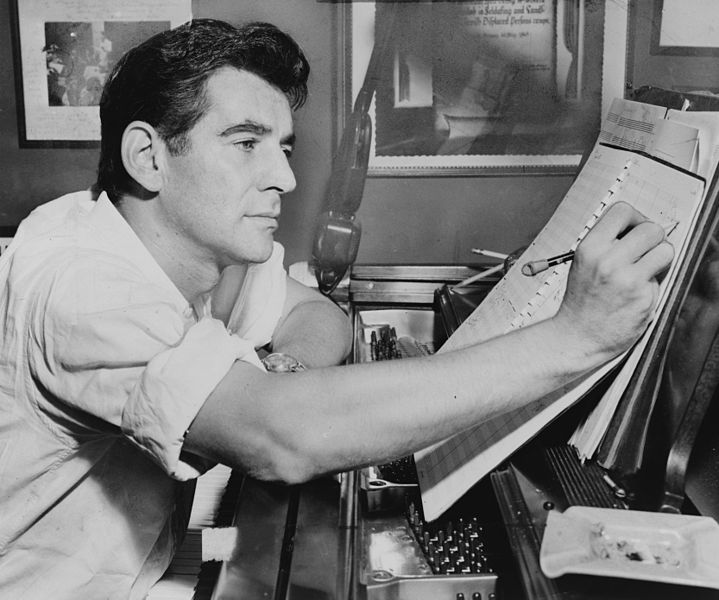

Today was the birthday of the great conductor, composer and music educator Leonard Bernstein, so we thought we’d take a look at some of his best moments on the Young People’s Concerts.

Bernstein was the newly appointed conductor of the New York Philharmonic when he took over the Young People’s Concerts, which he brought to a new level.

From 1958 to 1972, he conducted 53 performances at Lincoln Center, which were largely attended by a younger audience and were televised by CBS. And did CBS revere classical music back in the 1960s: not only did they air Bernstein’s long segments without commercial breaks, but, in 1962, they also commissioned Stravinsky to write a piece for the network, and the composer ended up penning The Flood.

For the Young People’s Concerts, Bernstein covered a wide array of topics, which ranged from musical theory (What is a melody? What is a Forma Sonata?) to in-depth forays into the works of specific composers. He had previous experience in music education for wide audiences, since he frequently starred in Omnibus, where he famously illustrated what Beethoven’s fifth would have sounded like if Beethoven had decided to keep some passages he ended up discarding. He mainly envisioned those concerts as TV shows because he believed in the scope of TV itself: he was convinced that, with the right teacher, it would be the most effective medium for musical education. And he was right: initiatives such as What’s Opera Doc by Warner Bros (1957) and several Tom and Jerry segments including “Tom and Jerry at the Hollywood Bowl” by Hanna and Barbera had proven to be successful and are still remembered as a gateway into classical music appreciation.

Despite the mockery he had to endure from critics such as Tom Wolfe, who called him “the Village Explainer” and ridiculed him for his compulsion to teach in a famous New York Magazine article, these hour-long episodes are, to this day, of invaluable quality. Whether you want to refresh your classical music knowledge or you simply want to relive a pleasant memory of your childhood, just watch one of his Young People’s Concerts videos. Youtube is pretty resourceful in that department.

Here are a few that you might find entertaining, and, other than learning, you will be delighted by the display of Bernstein’s larger-than-life personality.

What is a mode?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UGTT_VK2kVY

It’s hard to explain what a mode is to a layman who is too accustomed to the major-minor distinction, and, even if you read an encyclopedic entry, all the theory ends up confusing you more than before.

He is quick to clarify that “Modes have nothing to do with neckties or dresses.” Simply put, they are “strange scales that are neither major nor minor,” and the only reason laypeople are not very familiar with them is that, from Bach to the late 19th-century, composers hardly used them. When they resurfaced in compositions, they were hailed as “a fresh sound,” even though they had been around since ancient Greece. Without many frills, he proceeds to explain how to determine the seven modes.

Forever Beethoven

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wW9n6XV7x8E

In this video, Bernstein is absolutely transparent about his clear worship of Beethoven. Yet, to add some comic relief, he defines the composer as “a short, stubby fellow, a little provincial chap with bad skin and a comedic accent from the Rheinland, bad-tempered, stubborn, ill-mannered, arrogant, moody, grubby and a sloppy little man.” Yet, he is the most played symphonic composer that ever existed (at least when this footage aired).

Berlioz Takes a Trip

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tWrut6bxK0M

This episode became famous for equating Berlioz with 1960s counter-cultural artists. According to Bernstein, the Symphonie Fantastique was the first musical description ever made of a trip, 130 odd years before the Beatles. The five movements of the Symphonie are, according to Berlioz himself, a fever dream of an unnamed artist that is fueled by an opium overdose, but truth is, Berlioz’s imagination was vivid enough that he could conjure those visions without actually taking anything. “His opium was simply his genius,” Bernstein stated.

Liszt and the Devil

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aGRIt6fXoVg

Why is Liszt’s Faust Symphony such a good work but is hardly ever performed, especially given that he was the greatest pianist of his time?Did Liszt identify with Goethe’s Faust, considering he avidly read the play? In a sense, Bernstein argues, Liszt was a little like Goethe’s Faust himself: daring, inquisitive, eager to do and experience everything. In the Faust Symphony, he even wrote atonal music one century before it became “the thing” to write.