Music theory covers a bewildering array of considerations, elements, and aspects that surround this wonderful art. One of these elements is the concept of musical texture that as you might well imagine can account for a plethora of possibilities. What often makes the description of these elements, like texture, easier to agree on are common terms and phrases.

Amongst the more used and accessible are what I loosely call ‘phonics’. What I am referring to, as many of you will know, are the following three words: monophonic, homophonic, and polyphonic. From these three terms, we will be in a strong position to look in more depth at what they mean and how they directly apply to all music.

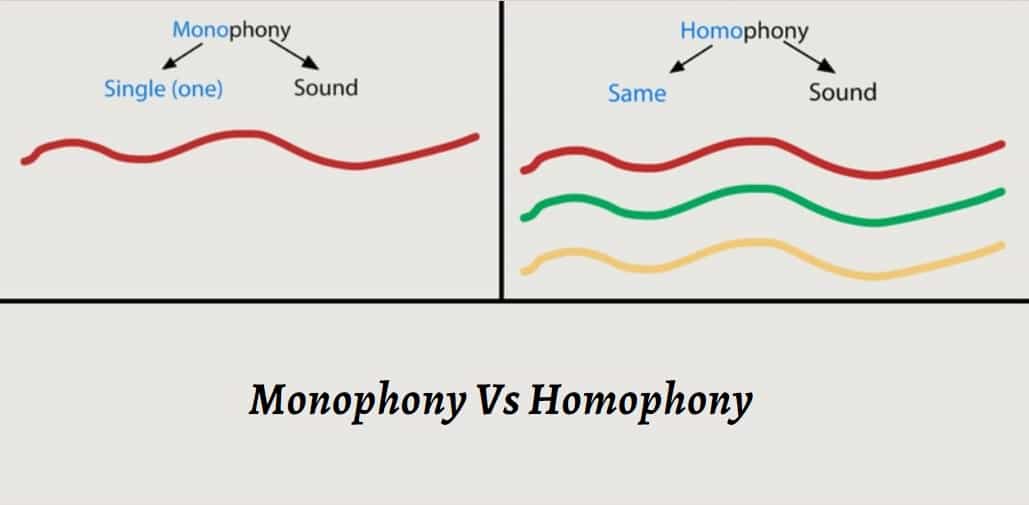

Monophony Vs Homophony

From the title of this article, a focus on only two of these key terms was needed, but I feel it is important to add the third for a clearer context and hopefully deeper understanding. When we describe a piece of music as being monophonic then we are discussing a single line of music without accompaniment or indeed anything else at all. There are no chords to provide harmony, or counter-melodies to add interest, only a singular tune to carry the composer’s intentions.

Consider the word mono that derives from the Ancient Greek word monos meaning single or alone. An orchestral example of this would be the opening of Stravinsky’s ‘The Rite of Spring’ that opens with the haunted, strained sound of a solo bassoon playing at the very top of its range. Another good example of monophony could be a ‘folk song’ that is commonly performed by a single vocalist who is unaccompanied. Similarly, music from the early Medieval Era called ‘Plain Chant or Gregorian Chant’ has a monophonic texture.

What monophonic does not mean is that other musical features are absent in any given piece. Just because there is a single melody performed perhaps only by an individual, the music can still have changes in dynamics (volume), tempo (speed), articulation (how a note begins and continues), to highlight a few common possibilities.

As we explore the concept of musical texture further, you might find the next word you come across in an encyclopedia or dictionary of music is homophonic or homophony. Here music moves into another textural territory that will be familiar to nearly everybody even if they are now aware that this is how it is described. How homophony translates into music is essentially a tune/melody plus an accompaniment. Not always, but many times, this means the tune takes a higher register above a chordal accompaniment. This can be easily illustrated by choosing a piano sonata by Haydn or Mozart where the use of homophonic textures is common and brilliantly applied. A further secular example would be a singer/songwriter, using their voice for the production of the melody whilst supporting themselves on a guitar or piano perhaps. In this way, homophony can be thought of as a remarkably familiar textural device.

Turning to the third term, polyphony/polyphonic, we encounter a very different musical texture from the previous ones. As I’m sure you will be aware, poly stems from the Ancient Greek word, polys meaning much, many, or more than one. How does this connect to a musical texture? Remember, monophonic referred to a single sound; homophonic to a melody plus chordal accompaniment, and polyphonic is used to describe music that combines two or more different melodies. As a description, it appears to be quite complicated, and placed in a piece of music it can certainly give that impression.

I find that one of the clearest ways to illustrate what polyphonic music sounds like is to look at a Bach fugue: perhaps one from the 48 Preludes and Fugues from the Well-Tempered Klavier. Bach was a master of polyphony and if accounts are to be believed, brilliantly able to improvise a four-part fugue from any given melody. What you hear in these works and others by the great Baroque composers, is a piece that contains independent (but related), melodies that sound together and interact to create polyphony.

Each of the three musical textures above has its individual merits in terms of a particular composition. Composers exploit different textures in compositions to bring diversity and interest to their work. These textural devices when creatively used in conjunction with other musical elements bring about works like the Bach 48 Preludes and Fugues that have thrilled performers and audiences alike for hundreds of years. No singular texture has a particular strength over another, it boils down to what the composer feels is the best ‘fit’ for the music they are developing.

If you listen to early forms of music such as Gregorian Chant, the monophonic texture of this ancient music is, I find, beautiful and completely in line with the philosophy of the time. The music was considered to be secondary to the sacred texts and so the thought of music as richly complex as a polyphonic piece might be would have been vehemently resisted. On the other hand, take a famous piece like the opening movement of the so-called ‘Moonlight Sonata’ by Beethoven. If you play the melody alone, as a monophonic piece, all the colors, and subtleties of harmony are lost and the tune on its own sounds lost and incomplete. The ‘need’ for a homophonic texture in this piece is exactly right.

There is no clear winner in the contest of textures. Monophonic music has just as much to offer the performer or the listener as homophonic music. Some might argue that polyphonic music presents an information overload, but it too has its place in the library of textural possibilities. With the luxurious quantity of music that the internet provides subscribers, it may be up to the individual to make up their own minds as to whether or not monophony or homophony offers a more favorable musical set of options.