Western classical music has developed a system of notation that has spanned nearly ten centuries. The results of this gradual process of evolution and refinement have brought us to a system of notation that allows for almost any musical idea to be accurately represented.

This is in itself quite an achievement as this means that tens of thousands of musicians accept and recognize the notation that currently appears before us as a score.

In fact, such is the sophistication of present-day notation that composer’s scores come in a huge variety of complexities depending on what they wish to convey to the performers.

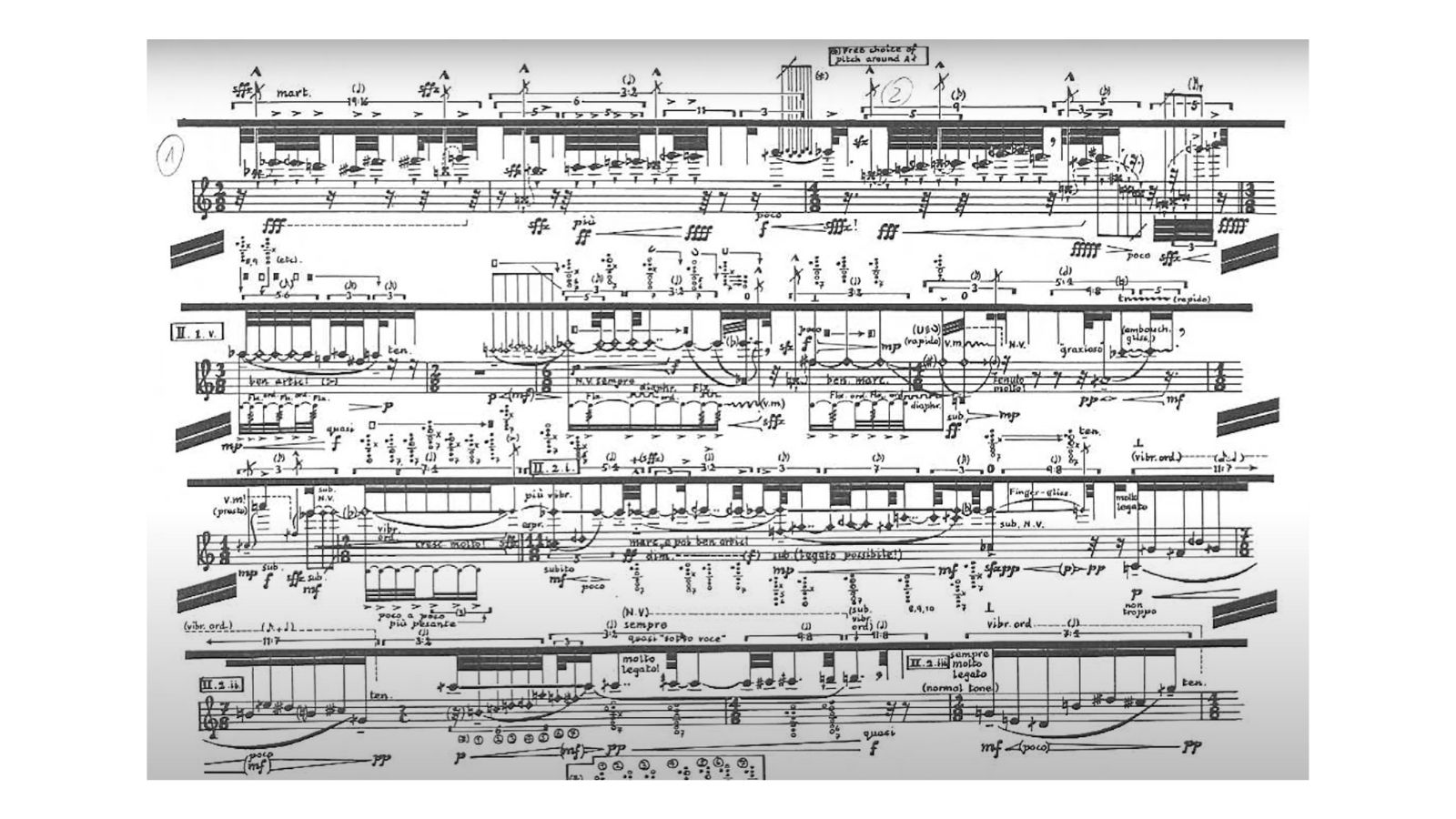

Here, for example, is a page of a score by Brian Ferneyhough that pushes the limits of notation almost to breaking point. You can imagine the challenges of actually trying to perform this piece.

As hard as it may be to believe, this is still using traditional notation, just at the more end of the spectrum.

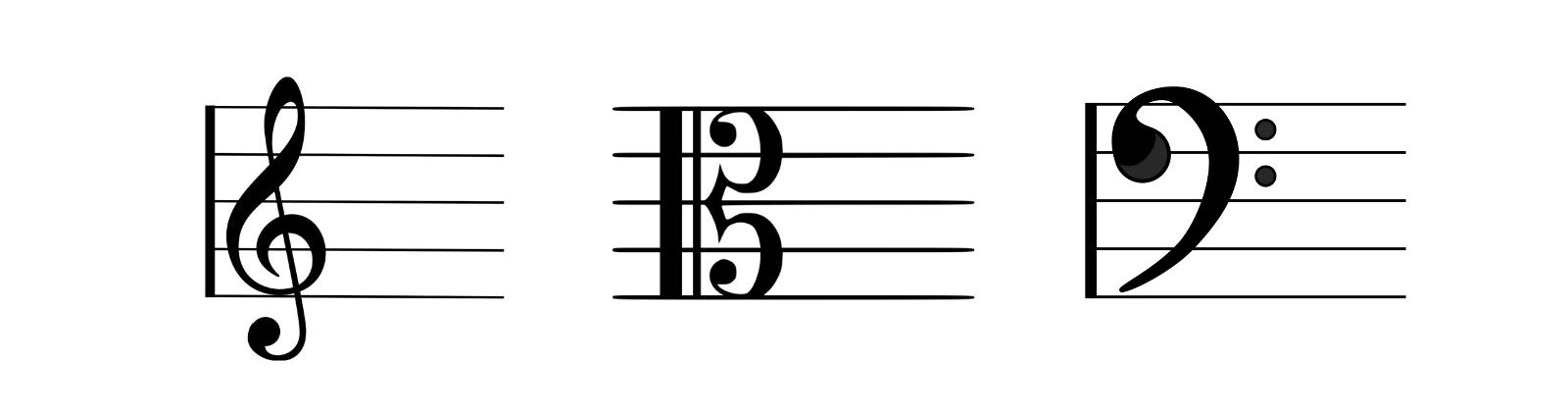

With the standardization of Western notation, certain customs or practices have become established. Clefs, for instance, are now a firm fixture in musical notation.

The three most commonly used are the treble, the alto, and the bass clefs. Each of these clefs is written at the start of the five-line stave to indicate the notes on that stave. (See clefs below)

You may already be familiar with these clefs. You might have come across the acronym every-good-boy-deserves-favor, with each word’s first letter indicating the notes to play on the lines of the treble stave (from the bottom up).

Different notes apply to each clef. The importance of these staves and clefs is that the communication of musical ideas from composer to performer is efficient and constant.

In this way, both the composer and performer have clear lines of communication. Without this, composers may notate completely inappropriately or in a way that the performer then has to interpret. Neither of these situations is desirable.

When you look back to the notation JS Bach used on his original manuscripts, it’s quite hard to decipher what clef he is notating unless you already are clued into JS Bach’s notation.

This is not to say JS Bach wrote incorrectly or inconsistently, simply that some of the conventions and practices of the 17th century are quite different from those of today.

The piano didn’t exist in JS Bach’s day, although it’s thought he may have encountered an early version of it in the final years of his life. According to some sources, JS Bach was not overly impressed.

Like all the other instruments that align with the Western Classical Tradition, the piano has become a stalwart of the music scene. With this central placement in musical life, the piano has rightly been given a piano clef(s).

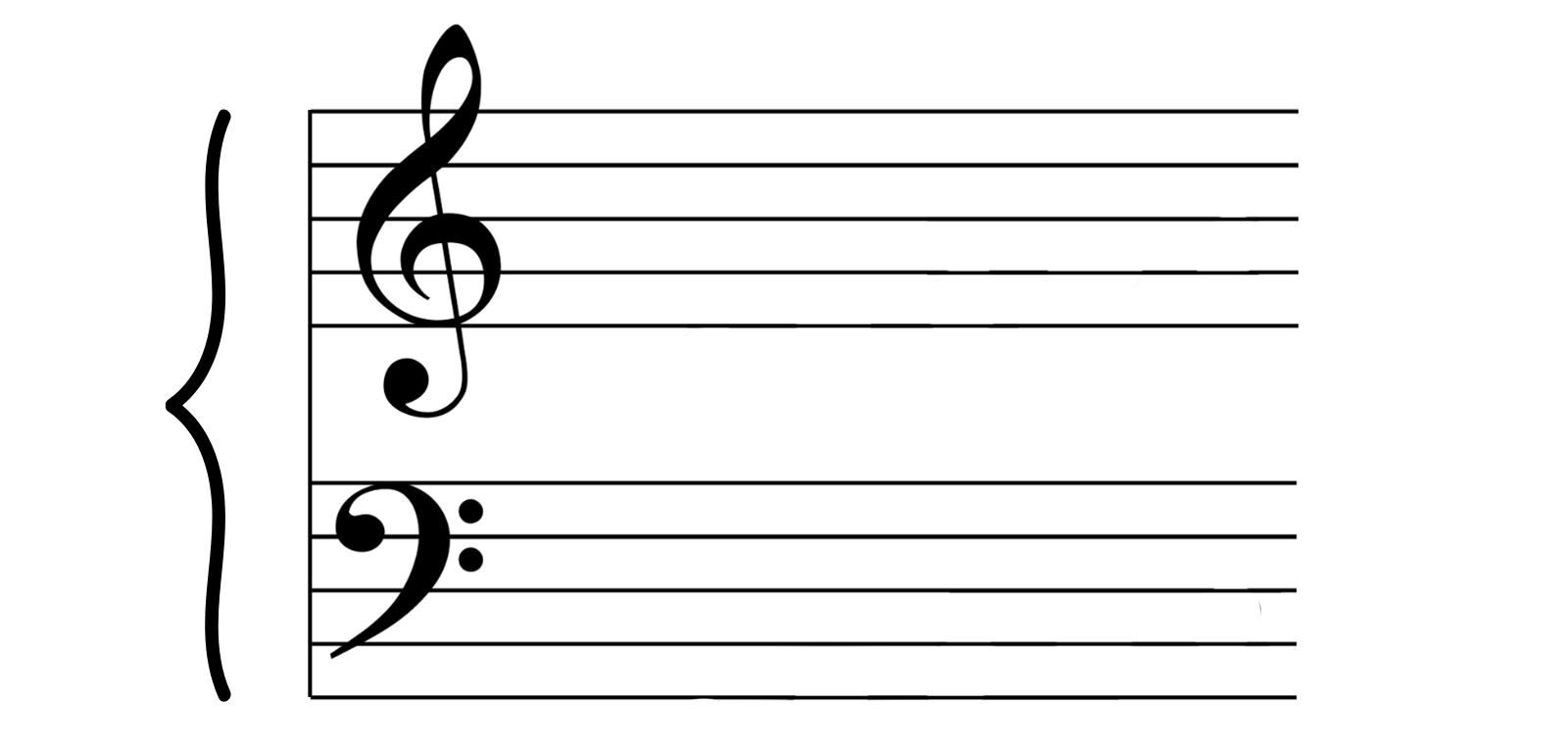

Piano Clefs

This most commonly takes the form of a treble clef with a bass clef underneath it. Sometimes this type of arrangement of staves is referred to as the grand stave. What that means is that the two separate clefs are joined together indicating this is for a single instrument.

This piano clef or stave has become the expected standard way of notating for a piano. The two clefs provide the composer with enough range to encompass the full seven-and-a-quarter octaves of the standard piano.

Naturally, the full expanse of the piano will go well below and above these two staves, but this offers a good middling compass enough for many compositions.

It is also an easy set of clefs to read, remembering that the treble clef is for the right hand and the bass clef is for the left hand of the pianist. There are exceptions where the pianist may cross hands, but this is often indicated in the score.

Additionally, you may find that the clefs change. This is an option where perhaps the composer wishes the pianist to play only notes in the highest or lowest registers of the piano.

It, therefore, makes sense to alter the clefs to both treble or both bass clefs. Commonly, this would then be amended later in the piece as the music evolves to better suit the composer’s intentions.

There are some interesting variations on this standard model of staves. We’ve already seen how Brian Ferneyhough’s notation takes a trip to the very far reaches of traditional notation. Other more modest adjustments to the regular piano clefs also exist.

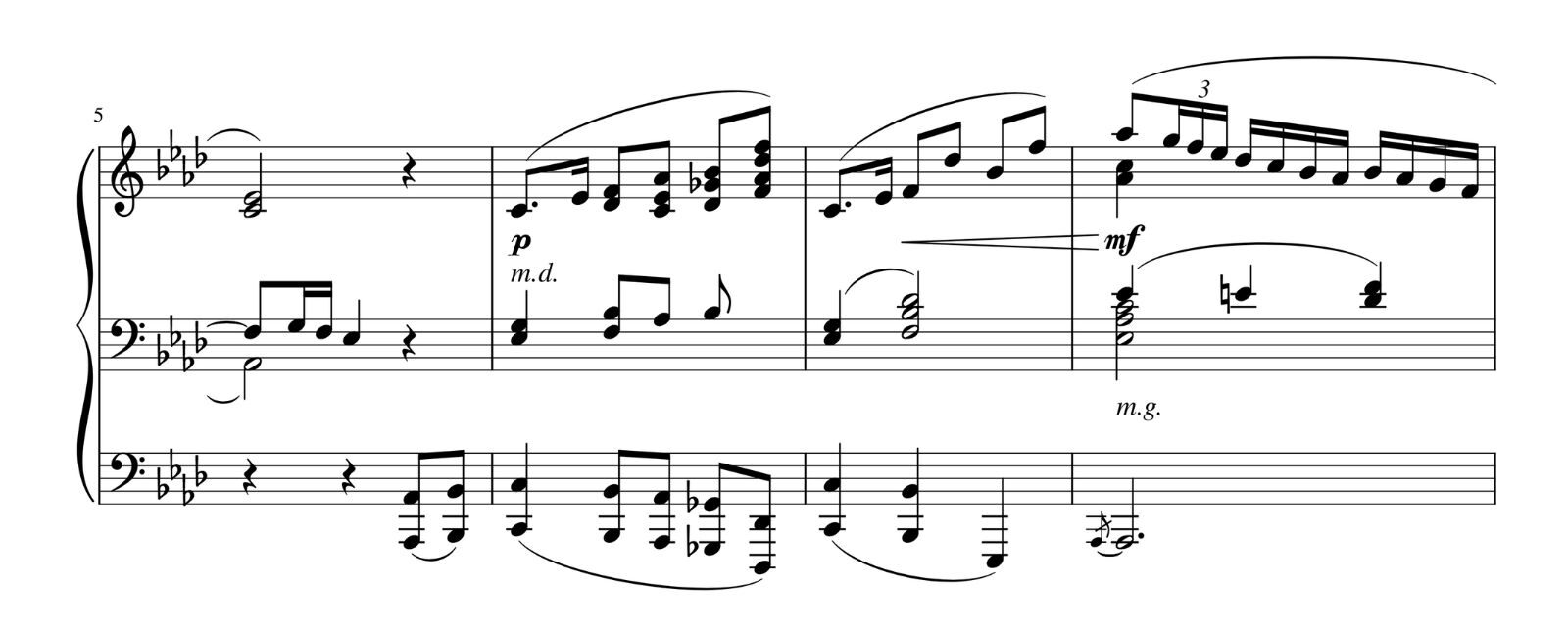

Above is an extract from a famous piano piece called Bruyères from Volume Two of Claude Debussy’s Preludes for Piano. What you’ll immediately notice is that whilst the notation is perfectly familiar, there are three staves.

In the top stave, Debussy writes a treble clef, with the two remaining staves employing bass clefs. There is also a bracket that Debussy writes in the second bar joining the middle and upper staves together. In the final bar, this changes to join the middle and lower staves.

What this means is that Debussy is not expecting a pianist with three hands to perform this music but for the performer to play the bracketed sections with the same hand.

This is why the low A flat has a grace note preceding it, allowing the pianist to jump the left hand from the A flat up to the four-note chord. It’s impossible to play any other way.

Debussy could indeed have notated this on a standard piano stave but this use of three staves and three clefs makes the clarity of the notation far greater.

Finally, I thought I’d show an example of a kind of double piano stave. This extract is taken from the final section of the C sharp Minor Prelude by Sergei Rachmaninov.

Not only do we see here just what an incredible pianist and composer Rachmaninov was, but the creative invention he uses to notate his ideas. Like the Debussy score, this offers the performer the most direct representation of Rachmaninov’s intentions.

The upper clefs are for the right hand, and the lower clefs are for the left hand. It’s not easy to play, but this choice of notation helps enormously.