Rhythm is a vital element of music. It is one that we respond to almost innately whether a pounding techno-beat or a lilting waltz, rhythm is part of who we are.

It is said that it is one of the first things we are aware of invitro as we feel, perhaps even listen to the heartbeat of our Mothers. If true then we are deeply rhythmic beings, who respond to and live by something that occurs naturally around us and within us.

There are many angles to analyse and discuss rhythm in music. Different rhythms and tempos directly affect the melodic, harmonic, textural and structural parts of any piece of music.

One of the most common is often brought up with students who encounter Jazz or Blues music for the first time. Some notice that the rhythmic feel is markedly different in Jazz or Blues, in a way that can be challenging to fully explain.

If you have taken a more traditional route of learning an instrument as I did, you followed a methodology that had been established long before the advent of genres like Jazz.

This means a study of largely Western Classical music and is sometimes limited to late Baroque, Classical and Romantic compositions. When I can across Jazz for the first time, its rhythmic subtleties captivated me and spurred me on to discover more clearly how they worked.

As a small point of interest, one of the key pieces for me was actually a brilliant amalgam of jazz and classical traditions in the Clarinet Concerto by American composer Aaron Copland.

He composed the work for Jazz Clarinettist and band leader, Benny Goodman who did much to bridge the then chasm between these two genres of music.

What Copland achieves in this concerto is a completely convincing blend of 20th Century classical music and jazz that cleverly weaves several of Goodman’s riffs into the concerto.

Here then is where the topical dilemma and where we encounter the idea of a straight and a swing rhythm.

Swing vs Straight Rhythm

What you may not expect having read the previous four paragraphs is that these rhythmic variants can and do occur in both Jazz and Western Classical music.

What perhaps distinguishes the patterns in Jazz is that it is often the central rhythmic feature of the genre that makes jazz sound the way it does.

To coin an Irving Mills, phrase his 1931 hit with Duke Ellington, “It Don’t Mean a Thing if it ain’t got that swing!” It may now be a bit of a cliché, but for me, this encapsulates the whole essence of jazz.

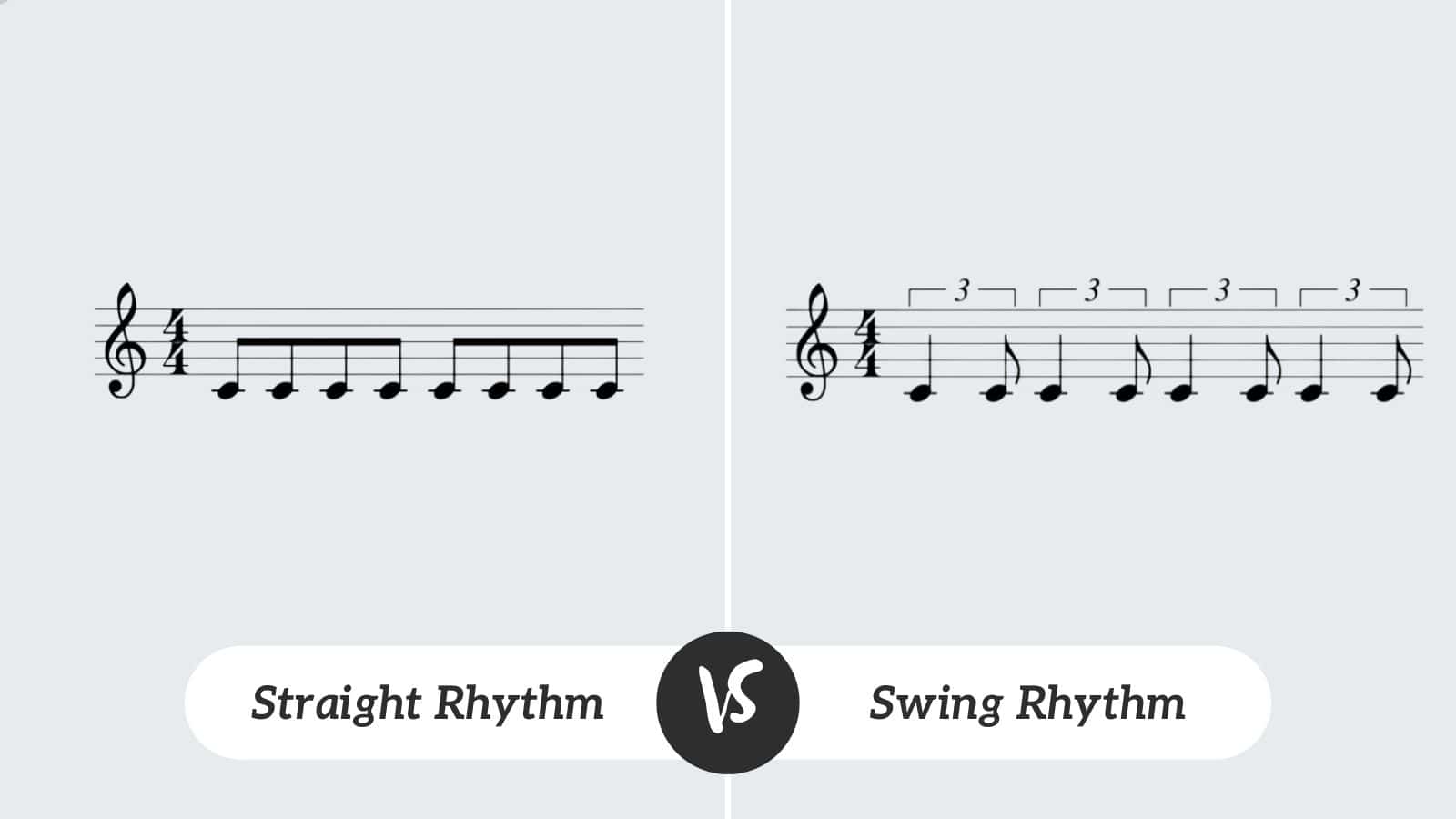

Swing rhythm is notoriously difficult to accurately capture using traditional methods of notation.

There are many variations of written swing rhythms, none of which really captures the feel of the music. In the final analysis, it is up to the skill of the performer to realise the notated rhythm, assuming they’re reading from a chart or lead sheet.

In Classical music, compound rhythms are very common. A compound rhythm is one of the lower numbers in a time signature is 8 or 16. (On occasions a 32).

The divisions of the beat in 6/8 for example are two groups of three quavers (eighth notes). If you remove the middle quaver from each of the two groups you have what amounts to a close swing rhythm.

Here are a couple of standard notations for indicating a swing to the rhythm in jazz. You’ll notice that both of these notations indicate swing at the start of the symbol.

They also both are intending the performer to produce the same result even though the rhythm of the notes to be changed is different. Both of these ways of indicating a swing rhythm are quite commonly found in printed music.

They do present a dilemma for the less experienced player and also require the performer to remember that this lasts for the duration of the movement of the piece.

Many pieces of Western Classical music, notably from the Renaissance, Baroque and Classical periods use old dance forms on which to hang new musical ideas.

Often it was these old courtly dances that would have had a compound time, even a swing to them that then filtered down into the eras of music as time unfolded.

And, these rhythms are amongst a whole host of other options, so even though they certainly do appear in Western Classical music, they are not exclusive.

Returning to jazz, the straight quaver also plays a vital part. As you will be aware, jazz has a massive emphasis on improvisation. It is the vehicle by which performers demonstrate their technique, and inspiration and express their emotions.

Naturally, swing rhythms litter jazz tracks but if you listen hard you can frequently hear jazz performers mixing it up a little.

Both swing and straight rhythms are employed by jazz performers in their solo passages to generate rhythmic diversity and interest. It also shows considerable technique fringed with expression.

In Funk music, you’ll hear more straight rhythms (all be it syncopated ones), which are a characteristic of this branch of jazz. There are also elements of rock in the world of jazz too where tracks also adopt a straight-eight feel as opposed to swing.

From the point of view of a performer who has a reasonable level of experience, straight-eights present a simple rhythmic challenge.

Each quaver note is evenly played, similar to the next unless the composer has added a notation to indicate otherwise. By this I mean, an accent, staccato, or tenuto mark perhaps.

When it comes to the swing rhythm then interpreting what the notation shows can prove problematic, even confusing. It requires a knowledge of jazz and better still a feel for the genre and that is not always easy or quick to develop.

Both rhythms have their secure place in music. They existed before any attempt to write them down existed. They are a natural expression of how we feel and how we move and both are fully essential to the music of the past and the future.