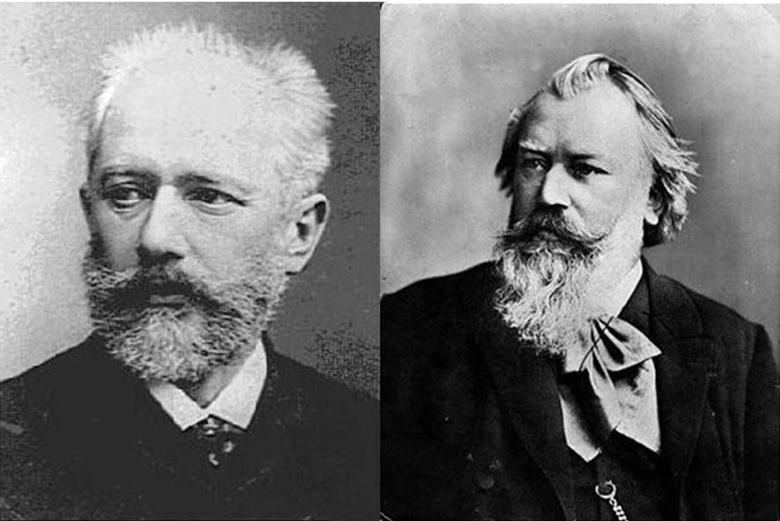

These two great composers were born on the same day, seven years apart, and it is known that they could not stand each other. It is fun to learn what happens when two fine composers of different temperaments first meet. One account is by the hostess of their original meeting, Anna Brodsky (from ‘Recollections of a Russian Home: A Musician’s Experiences’, by Anna Brodsky, Manchester, 1904)

Note: Russian violinist Adolph Brodsky (1851-1929) championed Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto in D Major, which was completed in 1878 for Leopold Auer, who declared it unplayable. However Brodsky was so impressed he premièred it in 1881 with the Vienna Philharmonic under Hans Richter. It is now recognized among the greatest violin concerti of all time, with Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Bruch and Brahms. During his career Brodsky accepted various posts in Vienna, Moscow, Leipzig, New York and finally in Manchester. In 1904 his wife Anna Brodsky published her reminiscences of her childhood in Russia, her life with Adolph, and their home in England. Her book was so well received a second edition was released 10 years later.

One of the most delightful episodes in her book concerns meetings between Brahms, Grieg and Tchaikovsky at the Brodsky home in Leipzig.

“In the winter of 1887 the Gewandhaus Committee invited Tchaikovsky to conduct some of his own compositions, and as he had received similar invitations from other towns in Germany, he decided to accept them and so, for the first time, came abroad to conduct his own works. He arrived in Leipzig on Christmas Eve: it was a cold frosty evening, and the snow lay thick on the ground. My husband went to the station to meet Tchaikovsky, and my sister Olga and her little son who were our guests at that time helped me to prepare our Christmas tree. We wished it to be quite ready before Tchaikovsky arrived, and to look as bright as possible as a welcome for him. As we were lighting the candles we heard the sound of a sledge, and soon after Tchaikovsky entered the room followed by Siloti and my husband. I had never seen him before. Either the sight of the Christmas tree or our Russian welcome pleased him greatly, for his face was illuminated by a delightful smile, and he greeted us as if he had known us for years. There was nothing striking or artistic in his appearance, but everything about him the expression of his blue eyes, his voice, especially his smile, spoke of great kindliness of nature. I never knew a man who brought with him such a warm atmosphere as Tchaikovsky. He had not been an hour in our house before we quite forgot that he was a great composer. We spoke to him of very intimate matters without any reserve, and felt that he enjoyed our confidence.

(photo: Percy Guttenberg, Manchester, circa 1907, postcard published by the Rotary Photographic Co Ltd)

The supper passed in animated conversation, and, notwithstanding the fatigues of his journey, Tchaikovsky remained very late before returning to his hotel. He promised to come to us whenever he felt inclined, and kept his word. Among his many visits one remains especially memorable. It was on New Year’s Day. We invited Tchaikovsky to dinner, but, knowing his shyness with strangers, did not tell him there would be other guests. Brahms was having a rehearsal of his trio in our house that morning with Klengel and A. B. — a concert being fixed for the next day. Brahms was staying after the rehearsal for early dinner. In the midst of the rehearsal I heard a ring at the bell, and expecting it would be Tchaikovsky, rushed to open the door. He was quite perplexed by the sound of music, asked who was there, and what they were playing. I took him into the room adjoining and tried to break, gently, the news of Brahms’ presence. As we spoke there was a pause in the music; I begged him to enter, but he felt too nervous, so I opened the door softly and called my husband. He took Tchaikovsky with him and I followed. Tchaikovsky and Brahms had never met before. It would be difficult to find two men more unlike. Tchaikovsky, a nobleman by birth, had something elegant and refined in his whole bearing and the greatest courtesy of manner. Brahms with his short, rather square figure and powerful head, was an image of strength and energy; he was an avowed foe to all so-called “good manners.” His expression was often slightly sarcastic. When A. B. introduced them, Tchaikovsky said, in his soft melodious voice: “Do I not disturb you?” “Not in the least,” was Brahms’ reply, with his peculiar hoarseness. “But why are you going to hear this? It is not at all interesting.” Tchaikovsky sat down and listened attentively.

The personality of Brahms, as he told us later, impressed him very favourably, but he was not pleased with the music. When the trio was over I noticed that Tchaikovsky seemed uneasy. It would have been natural that he should say something, but he was not at all the man to pay unmeaning compliments. The situation might have become difficult, but at that moment the door was flung open, and in came our dear friends Grieg and his wife, bringing, as they always did, a kind of sunshine with them. They knew Brahms, but had never met Tchaikovsky before. The latter loved Grieg’s music, and was instantly attracted by these two charming people, full as they were of liveliness, enthusiasm, and unconventionality, and yet with a simplicity about them that made everyone feel at home. Tchaikovsky with his sensitive nervous nature understood them at once. After the introductions and greetings were over we passed to the dining-room. Nina Grieg was seated between Brahms and Tchaikovsky, but we had only been a few moments at the table when she started from her seat exclaiming: “I cannot sit between these two. It makes me feel so nervous.” Grieg sprang up, saying, “But I have the courage”; and exchanged places with her. So the three composers sat together, all in good spirits. I can see Brahms now taking hold of a dish of strawberry jam, and saying he would have it all for himself and no one else should get any. It was more like a children’s party than a gathering of great composers. My husband had this feeling so strongly that, when dinner was over and our guests still remained around the table smoking cigars and drinking coffee, he brought a conjurer’s chest — a Christmas present to my little nephew — and began to perform tricks. All our guests were amused, and Brahms especially, who demanded from A. B. the explanation of each trick as soon as it was performed. After dinner Brahms beckoned my little nephew to his side and putting his arm around him made all kinds of fun. I remember hearing him ask: “Are you collecting autographs? ” “No,” the boy said, “I collect stamps.” The answer pleased Brahms immensely who said again and again, “What a wise boy you are.” Brahms was a great lover of children, though he was sometimes fond of teasing them. Once when he was walking with Brodsky in the streets of Leipzig they met a boy whom Brahms stopped with the question, “Where did you lose your green feather?” The boy caught anxiously at the feather and looked at Brahms in astonishment. It did not occur to him that Brahms could not have known of the green feather had it not been still there. We were sorry when our guests had to go. Tchaikovsky remained till the last.

As we accompanied him part of the way home A. B. asked how he liked Brahms’ trio. “Don’t be angry with me, my dear friend,” was Tchaikovsky’s reply, “But I did not like it.” A. B. was disappointed, for he had cherished a hope that a performance of the trio in which Brahms himself took part, might have had a very different effect and have opened Tchaikovsky’s eyes to the excellence of Brahms’ music as a whole. Tchaikovsky had had very few opportunities of hearing it, and that was perhaps one reason why it affected him so little. During Tchaikovsky’s frequent visits to Leipzig we saw him in every possible mood, in all his ups and downs, and always loved him more as we knew him better. Being of an exceedingly nervous temperament, he passed from one mood to another very rapidly. One night I remember well. It was the evening before his début in Leipzig. A. B. was absent, playing at Cologne. My sister Olga and I had finished our supper some time before when Tchaikovsky suddenly called on us, apologising for being so late. We were struck by the sadness of his expression and thought he must have heard some bad news. We gave him a warm welcome without asking any questions, and did our utmost to cheer him. We soon succeeded, and he told us it was the thought of to-morrow’s concert which had depressed him so greatly, and that, if he could, he would have been glad to give up all his engagements and return to Russia immediately. Such excitements were often more than he could bear; they brought on moods of terrible depression in which he seemed to see death in the form of an old woman standing behind his chair and waiting for him. Tchaikovsky often spoke of death and still more often thought of it. He was greatly attached to life and loved many things passionately: people he knew, natural beauty, and works of art. He had no firm belief in a future life and could never be reconciled to the thought of parting with all that was beautiful and dear to him.

On another occasion his extreme sensitiveness revealed itself in a different way. A telephone wire had just been laid between Berlin and Leipzig. Tchaikovsky and Brodsky arranged to speak through the telephone, the former from Berlin and the latter from Leipzig. At the appointed time Brodsky went to the telephone office hoping to have a chat with his friend, but he had only uttered a few words when he heard Tchaikovsky say in a trembling voice, “Dear friend! Please let me go. I feel so nervous.” “I have not got you by the buttonhole,” said A. B., “You can go when you please.” Later on Tchaikovsky explained to us that as soon as he heard his friend’s voice and realised the distance between them his heart began to beat so violently that he could not endure it. Sometimes Tchaikovsky would send us a telegram from Berlin, or any other town where he happened to be, to this effect: “I am coming to see you. Please keep it secret.” We knew well what this meant: that he was tired and homesick and in need of friends. Once after such a telegram Tchaikovsky just arrived in time for dinner; at first we had him quite to ourselves, but after dinner, as he was sitting in the music room with his head leaning on his hand as was his custom, the members of the Brodsky Quartette quietly entered the room bringing their instruments with them as had been previously arranged. They sat down in silence and played Tchaikovsky’s own String Quartette No. 3, which they had just carefully prepared for a concert. Great was Tchaikovsky’s delight! I saw the tears roll down his cheek as he listened, and then, passing from one performer to the other, he expressed again and again his gratitude for the happy hour they had given him. Then turning to Brodsky he said in his naïve way: “I did not know I had composed such a fine quartette. I never liked the finale, but now I see it is really good.” This time he did not reproach us for having disobeyed his wish about the incognito. He was very fond of meeting the Griegs at our house and, knowing this, we arranged it as often as possible. The dinners were usually followed by music. Madame Grieg would sing her husband’s beautiful songs and he himself would accompany her at the piano. She always put great enthusiasm in her singing and stirred us deeply. It was a treat to hear her, and Tchaikovsky never failed to express his delight.

The composers soon became intimate friends and, as a token of his great esteem, Tchaikovsky dedicated to Grieg his Overture to Hamlet, a tribute which the latter highly esteemed. Having been a student of the Leipzig Conservatoire, Grieg was very fond of the place and was in the habit of visiting it every winter. Once he came to us with a manuscript; it was his Violin-Piano Sonata No. 3; he told us he was not quite pleased with it, but would like to try it with Brodsky. To enter with heart and soul into a new composition, to throw his whole energy into it, and then to introduce it to the public — all this was a special pleasure to Brodsky, he felt it like a vocation. He liked Grieg’s Sonata from the first, and seized on the opportunity thus offered with great enthusiasm. This enthusiasm soon affected Grieg, and, after carefully studying it together, they gave a magnificent rendering in one of the Quartette Concerts in Leipzig, 1890, Grieg taking the piano part. He confessed to us afterwards that he had nearly destroyed the Sonata, he liked it so little at first. Brodsky had about this time a somewhat similar paternal feeling for another new composition — the piano quintette of Sinding, also a Norwegian composer. He first introduced it to the Leipzig public, with Busoni taking the piano part. It was very well received by the general public: the “Signale” gave a ruthless critique upon it, but another paper defended it. A bitter controversy arose, and in consequence, Brodsky was asked to repeat the quintette that very season, when its success was still greater; Sinding, who was present, received a magnificent ovation. After this, Brodsky played the quintette in many towns, until it became a repertoire piece for Chamber Concerts. On account of the services which he had repeatedly rendered to Norwegian musicians and composers, Brodsky received in 1891 the St. Olaf’s Order, as a grant from the Norwegian Parliament. This distinction gave him great pleasure, since it did not come from any single person, but from the Norwegian people as a whole, being decreed by their representatives.”

Source: Recollections of a Russian Home: A Musician’s Experiences, by Anna Brodsky, Manchester, 1904