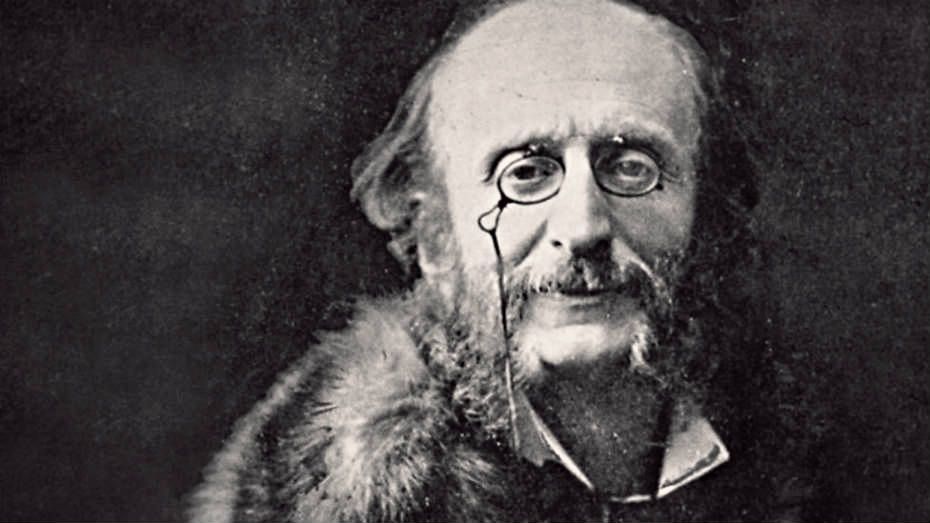

According to Richard Traubner in Operetta: A Theatrical History, Isaac Juda Eberst took the name Offenbach from a German city. He gave the name Jakob to a son who would later be known as the “Mozart of the Champs-Élysées” on June 20, 1819, in Cologne.

Late in his life, Jacques Offenbach said, “I have… a terrible, invincible vice, that is always to work.” His name, his nationality, and his even his religion would change (the last a condition for marriage to a Catholic woman) but his music would remain constant.

A precocious talent, Jakob began composing at age eight and playing the cello at age nine. In 1833, his father auditioned him at the Paris Conservatoire.

The Director of the Conservatoire, Luigi Cherubini, was (in Traubner’s words) “then a crotchety seventy-three” and unlikely to admit young students, especially of the foreign variety. He had already turned down a twelve-year-old Franz Liszt.

However, the young Offenbach proved an exception. Jakob, henceforth known as Jacques, began infiltrating the Parisian music scene.

In 1855, Jacques Offenbach decided to open his own theatre. Having spent his years as a virtuoso cellist cultivating wealthy acquaintances in salons and with the experience of a tenure as chef d’orchestre at Comédie Française behind him, Offenbach had little trouble finding investors and leasing a theatre near what would be the grounds of the Second Empire’s first Universal Exposition.

Big trouble came in the form of a license restricting entertainment to one-act performances with no more than four characters singing on stage and a mere twenty days to arrange an opening program.

On July 5, 1855 the “Bouffes-Parisiens” enjoyed a triumphant opening night with a piece that had caused controversy during rehearsal, Les Deux Avengles (Two Blind Beggars), turning into the hero of the night.

Tours of this show in London and Vienna inspired these cities to nurture their own forms of operetta. W.S. Gilbert (of Gilbert and Sullivan) would later translate Offenbach’s Les Brigands into English. Unmistakable echoes of the work appear in Pirates of Penzance.

Meanwhile, in 1850s Paris, Offenbach staged revivals alongside his original works to lessen the burden of composition. He also started a competition for up-and-coming composers to provide music for a libretto, which would then be performed by the Bouffes-Parisiens.

Offenbach had an eye for new talent; his first joint winners were Charles Lecocq and Georges Bizet.

In 1858, the licensing restrictions were lifted and Offenbach produced his first two-act operetta: Orphée aux Enfers (Orpheus in the Underworld). At this point, his theatre’s fate was tied to that of Orphée.

Offenbach did not have a head for business and his extravagant productions had left the Bouffes-Parisiens in dire straits. A lukewarm premiere left Offenbach scrambling to improve the piece with endless revisions.

Finally, one reincarnation prompted critic Jules Janin to declare the operetta a “profanation of holy and glorious antiquity” (Source: Traubner). This titillating condemnation, combined with the revelation that a flowery speech from one of the characters had been lifted verbatim from Janin’s own writing, led to a slew of sold-out shows.

The 1860s were a period of dizzying success for Offenbach, culminating in a worldwide frenzy over La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein, commissioned for the second Universal Exposition of Paris in 1867.

There was sadly only one way to go from there. The 1870s saw Lecocq ascend to prominence with La Fille de Madame Angot (1873) and Le petit Duc (1878) while Offenbach descended into mediocrity. But Offenbach never stopped working.

He scored one more hit with La Fille du Tambour-Major in 1879 and was busily writing a full-scale opera, Les Contes d’Hoffmann, at the time of his death on October 3, 1880.

Traubner compares Offenbach’s role in Second Empire France to that of a court jester. There can be no doubt that he made his audiences laugh. But he also attacked established powers with subversive wit.

Like Shakespearean fools, Offenbach often peppered his humour with profound insight. Some critics derogatorily categorize Offenbach’s work as “musiquette.” But really, what’s in a name? It’s the music we remember.

Very good article !