It is not uncommon when watching a performance, to wonder what exactly it is that the conductor of an orchestra does.

Occasionally you might spot the players from a section glance the conductor’s way but by and large, it appears that the orchestra, ensemble or choir are quite content to continue the performance without paying significant attention to the person waving the baton at the front.

Certainly, for professional performers, the conductor is broadly a point of reference during a performance to which they can turn to be cued, given instruction regarding the performance, or, reference the beat of the bar. Here is where we enter the territory of the title.

If you have ever taken an Associated Board music examination, you may have experienced or been expected to conduct a beat to piece played by the examiner.

On the other hand, you might have tried your hand at conducting an ensemble yourself, in which case you will have a clear idea of where I am heading here.

A huge quantity of music composed both past and present is either written in two, three or four beats in the bar. Each of these divisions of a musical bar requires a different beating pattern to accurately indicate the correct number of beats.

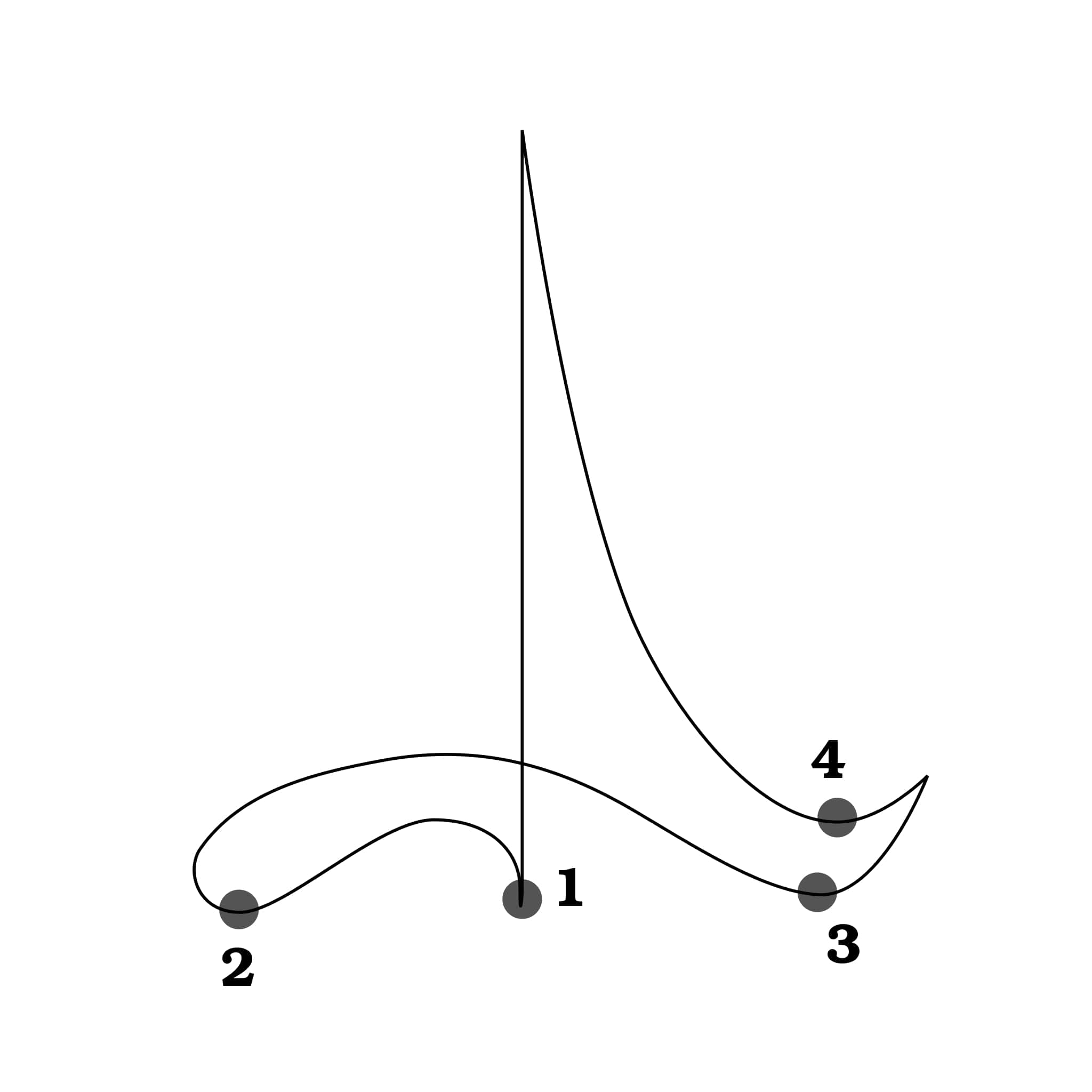

If, for example, you were to beat a two-in-the-bar metre you would make a sort of ‘I’ shape with your baton. If you were beating four-in-the-bar, then it’s more complex. This would require you to draw in the air, an upside-down ‘T’ shape. (See diagram below)

This more clearly shows the pattern a conductor would use if beating a four-in-the-bar rhythm. Remember, you begin at the top, come down, to the left, then to the right and back to the top where you began.

What you do initially bring your baton down and give the downbeat to the group you are leading. Likewise, on the last beat, your ascending baton provides what is known as the upbeat.

What Do Upbeats and Downbeats Do for the Orchestra

Why is this of importance? The simple answer is that it succinctly indicates to an orchestra, or another ensemble, where the first and last beat of each bar occurs.

This is important as music is written in such a way that bars always contain a first and last beat, so the performers can make sure they are playing their parts on the correct beat of the bar.

It might sound straightforward if most music is in regular beats to the bar not to lose count or lose your place, but actually, it isn’t.

This is especially true of larger instrumental or vocal groups that can perform complex, demanding music where it is easy to lose your way.

With the conductor consistently beating out the beats of the bar and often very clearly marking the up and downbeats, your performing job is an easier one.

There is another angle to consider. Not all music, especially contemporary music, that falls neatly into regular beats in a bar.

Some orchestral music, for instance, composed post-1900, contains numerous changes of time signature (beats per bar), as well as tempo (speed) changes.

If you are performing a composition like this, ‘The Rite of Spring’, is a great example, then having a conductor show you where each bar starts and ends is pretty vital.

This is true not only for you as an individual player, but in the orchestral setting for the entire group of players.

When you realise that it is not uncommon for an orchestra to contain upwards of one hundred performers, many with different parts to play, keeping them together is quite a job.

With the visual cue of an upbeat or downbeat provided by the conductor, the orchestra are not only more able to keep together but can also respond to subtle changes within the music.

What you may have seen when some conductors perform is that they are not in time with the orchestra but slightly ahead or even behind them.

In some cases, this may just be poor conducting, but in the majority of situations, it’s because the conductor is flexing the tiny details of the tempo to carve out a unique sonic experience.

It illustrates the importance of the role of the conductor as not rudimentary beat-keeper but interpreter and orchestrator of the whole performance. This in a very real sense is where the music comes to life and the conductor proves their worth.

Historically, there have not always been conductors in the form we recognise them with today’s orchestras.

There have only been orchestras of the size we have in the 21st Century for around a century and a half spurred onwards the composers of the late Romantic era.

And it was this expansion of the orchestra that required a leader to pull the gigantic forces together largely through the provision of an up and downbeat.

Stepping back a little further in time to the Baroque era, any direction of larger ensembles was often undertaken by the keyboard player who might well have also been the composer.

In the case of French court composer Jean Baptiste-Lully, he directed performances by beating out time using a large conducting staff completely unlike the light baton used by conductors today.

Lully would hammer out the beat on the floor using this quite formidable implement. One unfortunate day as the story goes, Lully was becoming increasingly frustrated with the performers and began to use considerable force with the staff.

This would have been fine if he had not accidentally brought the staff down onto his foot causing a nasty injury that eventually lead to the composer’s death. This was probably the most dramatic downbeat in musical history.