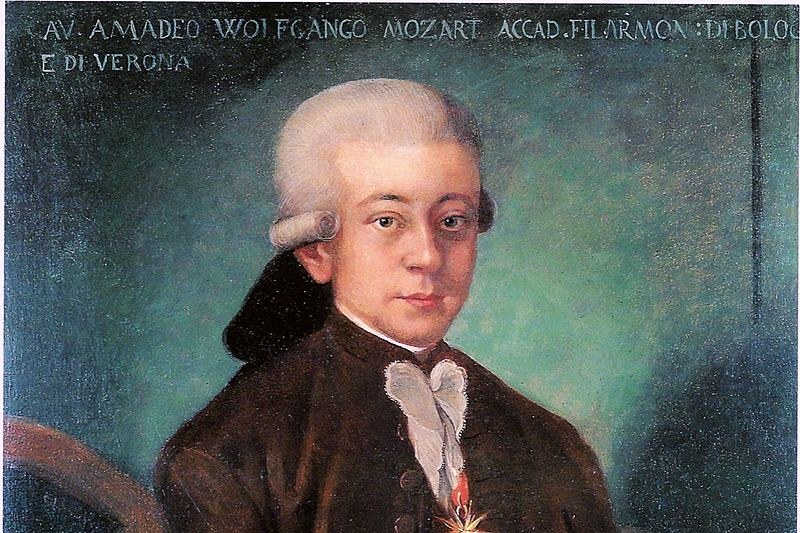

Opera buff or not, you are unlikely not to recognise the title above of one of WA Mozart’s most discussed, analysed and performed operas: The Marriage of Figaro.

This four-act opera was composed by WA Mozart in 1786 and carries the catalogue number K. 492.

The libretto takes its ideas from a piece loosely translated as The Mad Day, or The Marriage of Figaro, (La folle journée ou Le Mariage de Figaro) by Pierre Beaumarchais.

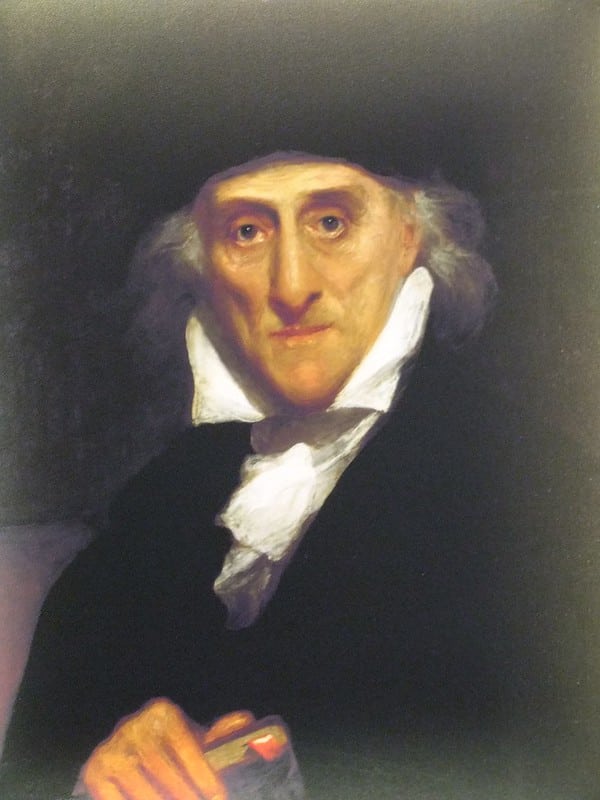

It was WA Mozart’s collaborator Da Ponte who transformed Beaumarchais’s text into the brilliant libretto. (Da Ponte went on to work with WA Mozart on Don Giovanni and Cosi fan tutte).

The Marriage of Figaro opera is raw and richly comic. It is felt by many to be perhaps the best opera WA Mozart ever composed.

Why Was The Marriage Of Figaro Considered To Be Controversial?

Where does the controversy stem from? What could be so offensive about a comic opera written by the leading Classical composer of his day?

One of the sources of friction is that it directly addresses the stark differences between the classes and the centuries-old conflict between them.

It was a struggle for Da Ponte to acquire Emperor Joseph the second’s royal permission to turn Beaumarchais’s Marriage of Figaro into the libretto for the opera.

This was because the Emperor considered the contents of the text objectionable and duly made sure it was banned from being performed as a play. Eventually, Da Ponte gained the Emperor’s permission and skilfully created the libretto.

What Da Ponte did was to effectively remove any offending references to the nobility and other thorny political challenges all of which he achieved in poetic Italian.

In this way, Da Ponte laid the foundations for the brilliance of WA Mozart’s score that at the point of the Emperor’s approval had not even been started. One clever edit from the original text by Da Ponte is the main rant against the nobility by Figaro.

This, whilst potentially providing a source of comedy in the opera would have also caused great controversy and the anger of many who patronise the opera.

Da Ponte altered the aria, dexterously making it a song about wives who are less than faithful which would have been equally funny but considerably less politicly hot.

The Marriage of Figaro is a sequel. This is the sort of word we more commonly hear today when we think of a film or television series but effectively, The Marriage of Figaro was a continuation of the story of WA Mozart’s earlier success, The Barber of Seville.

Many years later, following Count Almaviva’s successful marriage to Rosina, the scorned Dr Bartolo (Rosina’s suiter), is after Figaro’s life as revenge for helping the Count fulfil his designs on Rosina.

Figaro now is a servant for the Count but the Count himself has transformed into a terrible character who chases young girls, bullies servants, is unfaithful to his wife the Countess, and is not the pleasant aristocrat of yesteryear.

Where the issues arise for Figaro is that he is in love with the Countess’s handmaid Susanna. After much trickery and clever antics, the two servants eventually marry one another and the story ends happily.

Innocent enough plot as a comic opera? Yes, on the surface, but as you would expect, there’s more under the hood than the bodywork might leave you to believe. With Count Almaviva’s descent into depravity comes a natural controversy.

The figure of the Count becomes a stereotype of all inherited nobility and therefore one to ridicule, pity and despise. This is not the image the ruling classes would have appreciated.

The added dimension in the synopsis is that Count Almaviva intends and indeed keeps trying to exercise his right to sleep with Figaro’s bride-to-be, Susanna.

To 21st Century sensibilities this sounds like a malicious infringement of a woman’s rights. It is, except at the time when the story is set, the male members of the nobility could choose to bed any servant girl in his employ. This included Susanna.

All manner of fun and games ensue. Dr Bartolo tries to exact his revenge on Figaro by contracting him to marry an old woman (who is actually Figaro’s Mother), instead of Susanna.

The Countess and Susanna cook up a cunning plan to disguise themselves as each other and write a cryptic love letter to the Count.

Meanwhile, poor Figaro thinks Susanna really loves the Count until he eventually sees through her disguise. The Count becomes completely ensnared in the women’s schemes, and finally has to admit his faults and ask for his wife’s forgiveness.

What these final two acts demonstrate with absolute clarity is that the women in this opera are noticeably smarter and shrewder than any of the men. They run rings around each of them finally achieving the outcome that makes everyone happy.

Not only do Susanna and the Countess succeed in making the Count repent and cease his infidelity and cruelty, but they also manage to unite Figaro and Susana as well as solve several other problems for the smaller characters.

Sometimes it’s challenging to view The Marriage of Figaro through the eyes of an 18th-century person. The rules governing social conventions and structures were very different to the times we inhabit now.

Through art, it is often easiest, if at times dangerous, to protest or quietly rebel against the establishment and its expectations. This is particularly true when those with power have such power that they can dictate how those below them should live.

In The Marriage of Figaro, Da Ponte, and WA Mozart expertly weave their combined talents into an opera that superficially could be received simply as a funny story, but if you scratch just below the surface, the depths and devices of the work become immediately apparent.

In this way The Marriage of Figaro remains highly topical today, standing as it does as a challenge to entrenched views and questionable morals. When this is presented to you with the genius of WA Mozart’s score it is unmissable.